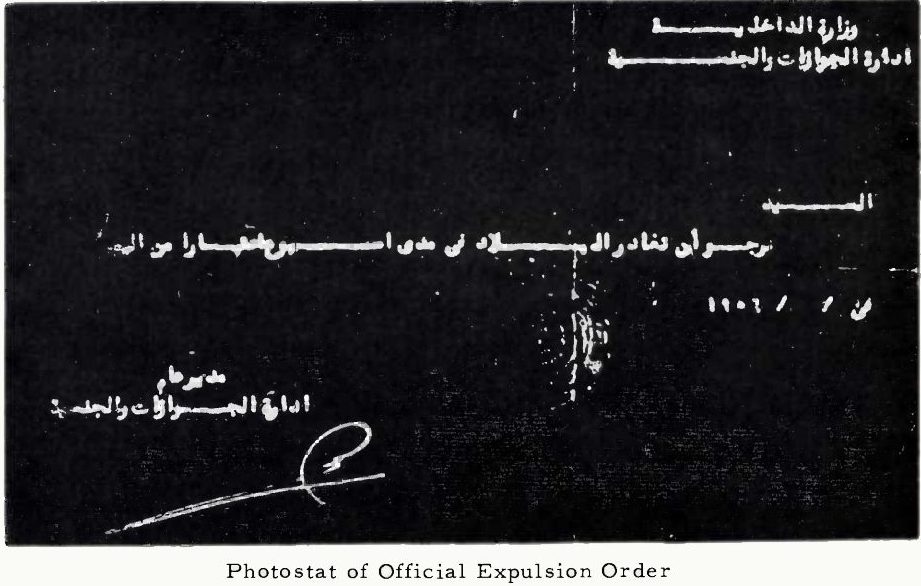

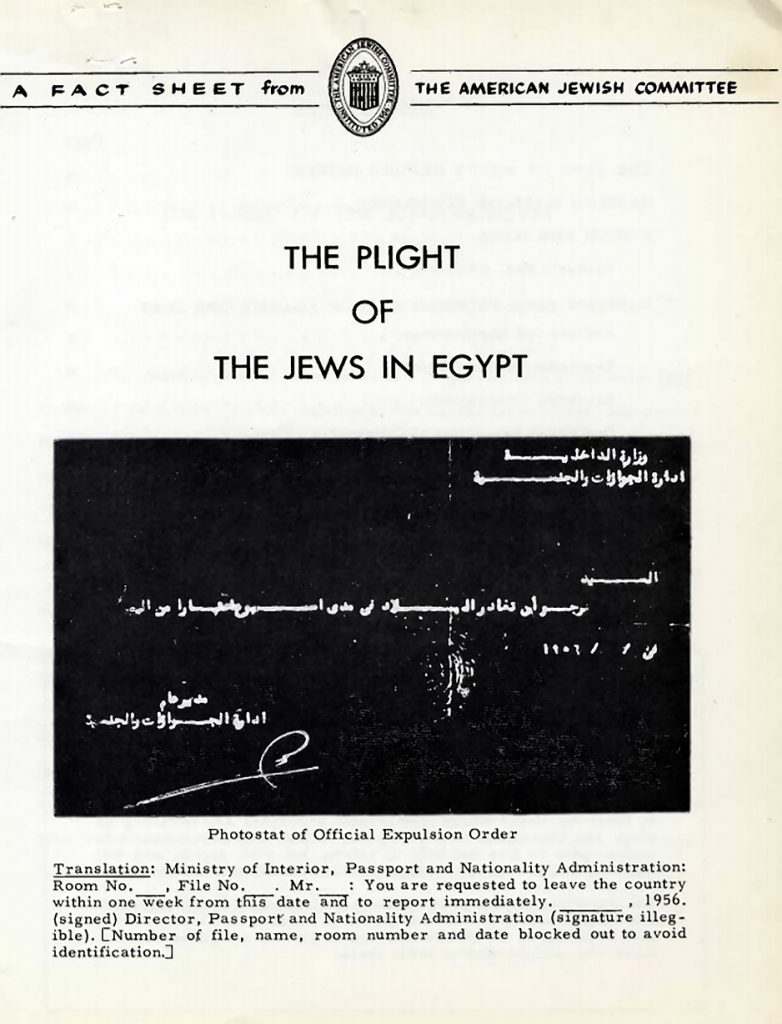

Photostat of an expulsion order instructing the recipient to leave to country immediately issued in Egypt, 1956. From “The Plight of Jews in Egypt,” a factsheet by the American Jewish Committee made available by the Historical Society of Jews from Egypt.

By Pablo Jairo Tutillo Maldonado

In September 2017, Eyal Sagui Bizawe, a Jerusalem-based Israeli film director of Egyptian Jewish origins, published an opinion article in Haaretz critiquing the Israeli Ministry of Education’s recent initiative to implement a new curriculum in the Israeli education system.

The new curriculum addresses the historical injustices experienced by Jewish communities of the Arab world, particularly the plight of Sephardi Jews — Jews who came from pre-Inquisition Spain — and Mizrahi Jews — Jews of Middle Eastern origin, who primarily resided in Muslim-majority countries.

While Bizawe accepts the introduction of more diverse perspectives into the educational curriculum around Jewish history in Israel, he says that the new curriculum overwhelmingly focuses on the persecution of Jews from modern Egypt, and claims that it forces Egyptian Jews into the collective memory of Jewish people being persecuted and expelled, when, Bizawe writes, “It’s indisputable that most of Egypt’s Jews were not expelled.”

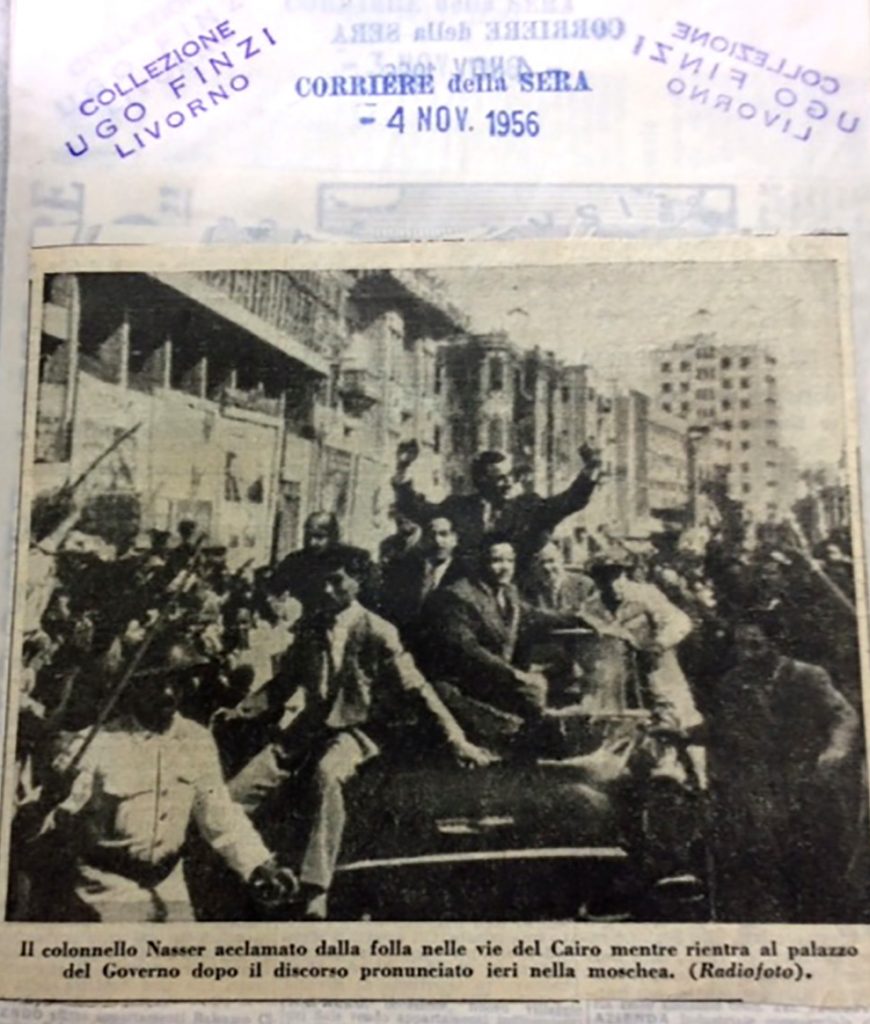

President Gamal Abdel Nasser parades through the streets of Cairo, heading towards the governmental palace after his speech at a mosque. Published November 4, 1956. From the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, Jerusalem.

But the forced migration and expulsion of various Jewish communities from Arab countries cannot be overlooked. The Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs estimates that the Egyptian Jewish population was between 75,000 – 80,000 at its height in 1948, when Israel became independent. In the decades afterwards, the Egyptian Jewish community left in multiple waves and diminished rapidly.

In the 2017-2018 academic year, I focused my research on the construction of national homogeneity in Egypt under President Gamal Abdel Nasser in the 1950s, and the social and political pressures that led to the forced migration of the remaining Jewish communities from Egypt in 1956. While the Jewish community of Egypt left in various waves and for various reasons in the last century, I chose to study the year 1956 specifically because of the documented actions perpetrated by the Nasser Administration that led to the forced migration of members of the Jewish population.

Egypt’s cosmopolitan past

Cairo and Alexandria were once cosmopolitan metropolises where many ethnic, religious and national minorities – Armenian, Christian, French, Greek, Italian, Jewish, Syrian – were highly integrated Egyptian members of their country and enjoyed a multicultural environment.

According to The Museum of the Jewish People at BeitHatfutsot in Israel, the 2,000 year-old Jewish community in Egypt made significant contributions to culture, education, health, government and other areas of Egyptian society. In modern times, the Ashkenazi, Sephardic and Karaite members of the Jewish population made it diverse in its makeup: Egyptian Jews had different traditions, religious observances, social and economic statuses, and political views. However, the rise of nationalism in Egypt in the 1950’s spurred the exit of these and other minority communities.

The forced migration of Egyptian Jews

Following the independence of Israel in 1948, the political situation in Egypt became more hostile towards Jews. The Jewish Virtual Library indicates that between June and November 1948, “bombs were set off in the Jewish Quarter of Cairo which killed more than 70 Jews and wounded nearly 200.” Yet thousands of Jews — approximately 40,000 — remained in the land they called home after Israel’s independence.

However, the 1954 regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser changed the posture of Egypt in the region and further affected the decreasing Jewish community in Egypt. In 1952, Nasser helped to overthrow the Egyptian monarchy, and as Egypt’s new president in 1954 he launched initiatives to nationalize politics, the economy and society.

On October 29, 1956, Israel, Britain and France attacked Egypt in response to Nasser’s decision to nationalize the Suez Canal, a crucial hub of transportation, commerce and trade for Europe. During this war, the Egyptian government declared all Jews enemies of the state, and immediately began a systematic expulsion, as described by historian Joel Beinin in his 1998 book “The Dispersion of Egyptian Jewry.”

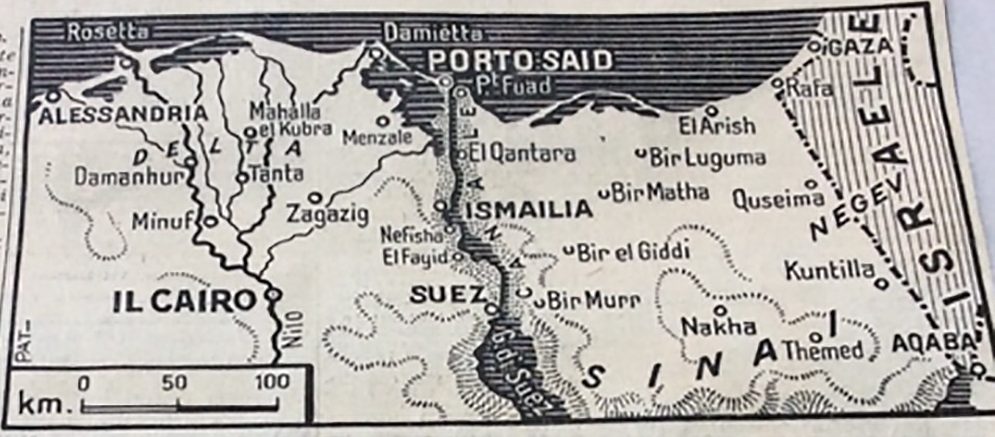

An Italian map of northeastern Egypt and Israel. Published November 3, 1956, from the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem.

In his book, Beinin notes that approximately 1,000 Jews, half of whom were Egyptian citizens, were arrested in various sections of Cairo in 1956. Beinin also highlights that 13,000 French and British citizens — a group which included many Jews — were expelled from Egypt as a response to France and Britain’s attack. Beinin adds that during this time, 500 Jews of non-British and non-French citizenship were also expelled, and 450 Jewish-owned businesses were confiscated following the government’s decision to nationalize the assets of British and French citizens in the country.

According to data from JIMENA (Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa), a California-based organization safeguarding the history and legacy of Jews from the MENA region, approximately 25,000 Jews left Egypt during 1956, leaving approximately 15,000 remaining in 1957.

“Espulsioni”

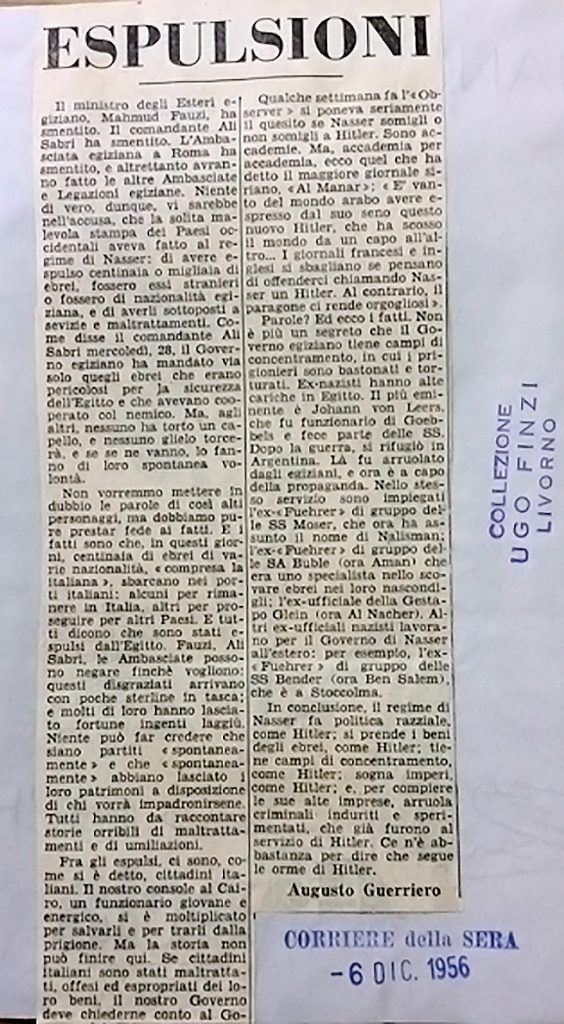

An excerpt from the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera documenting the arrival of Jews from Egypt. Published December 6, 1956. From the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, Jerusalem.

When I visited the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem in 2017, I came across relevant documents related to the expulsion of 1956. While I expected to read a lot of material written in Hebrew, I was presented with collections of newspapers in Italian. To my surprise, these newspapers reported that most of the Jews who left Egypt in 1956 ended up at various ports in Europe, places such as France and Italy, most likely because they were not affiliated with the political Zionist movement, and perhaps because they had previously obtained citizenship from those countries.

With the assistance of Sabrina Tatta from the UW French & Italian Studies Department, I was able to decipher an article titled “Espulsioni” (“Expulsion”) from an Italian newspaper named Corriere della Sera, which was dated December 6, 1956. The article reads: “Hundreds of Jews are disembarking in Italian ports. Some remain in Italy and others go to other countries…..They left their property and assets in Egypt . . . some with horrible stories of maltreatment . . . If they were Italian citizens stripped of assets and property, the government must ask for accountability.”

Jewish international organizations respond

The American Jewish Committee (AJC) released a factsheet in March 1957 on “The Plight of Jews in Egypt.” The cover of the factsheet contains the photostat of an Official Expulsion Order in Arabic issued by the Ministry of Interior, Passport and Nationality Administration that demands the recipient’s immediate exit from the country. The AJC factsheet highlights the systematic mass expulsion of Jews imposed by the Nasser regime.

“The Plight of the Jews in Egypt,” a factsheet from the American Jewish Committee, March 1957. Via the Historical Society of Jews from Egypt.

According to the report, on November 15, 1956, the Egyptian Ministry of the Interior required all Jews, regardless of citizenship, to report to the Ministry. At the Ministry offices, Jews were told to leave Egypt within a few days or face the risk of being placed in a concentration camp. The report indicates that Expulsion Orders were sent to Jews of every status. Upon exit, the report says, all Jews were required to sign a supposedly “voluntary” form renouncing all claims, property, and citizenship in Egypt. In other words, Jews were systematically forced to migrate.

The report concludes with statistics from February 10, 1957, about “ships leaving from Egypt with 8,500 Jewish refugees going to Europe, 2,092 to Greece, 3,855 to France, 2,600 to Italy, amongst others who left via airplanes to Switzerland, Belgium and other countries.” In this manner, the AJC’s factsheet presents significant evidence about the unexpected departure of thousands of Egyptian Jews in 1956.

In addition, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee had been communicating between its New York Office and Geneva Office regarding the property of the Jewish community in Egypt. I found letters from the year 1959 from administrators concerned about this property and the best way to recover it. Employees of the AJDC entertained the idea of sending an American non-Jew to investigate whether Egyptian Jews’ property was still in good condition, though they ultimately decided not to due to the expected unwillingness of Egyptian officials in the Foreign Ministry to offer reparations.

The uses of Mizrahi history

As I have demonstrated in my research, the expulsion of Jews in 1956 from Egypt cannot be underestimated. These narratives of forced migration should be included in educational curricula: The historical injustice experienced by the Jewish communities of the Arab world is real and has been corroborated by many academics, humanitarian organizations and families.

However, even though he is not a historian, Eyal Bizawe’s criticism of the Israeli Education Ministry’s new curriculum is very relevant to Israel’s contemporary politics and history. As an Israeli citizen of Egyptian Jewish heritage, Bizawe raises important questions about how the historical experience of the Jews of the Arab world (the Mizrahim) is constructed in the Jewish world and in Israeli society.

Bizawe is concerned about how the Israeli government is utilizing the history of its Mizrahi population today, and specifically how this history benefits the state. Israel, like any other state, has been repositioning itself in the region by utilizing parts of history that serve its national and security interests. Bizawe believes that the new curriculum supports the Israeli right-wing narrative that Middle Eastern, particularly Arab Muslim, regimes and societies are not friends, but rather historical enemies and persecutors of the Jewish people – a grand narrative that serves to justify the factionalized relationship between Israeli Jews with Palestinians and neighboring Arab and Muslim societies.

Likewise, the states surrounding Israel have also constructed grand narratives about Israel and Jewish people as historical enemies. It is important for people on both sides to understand that these grand narratives are driving people apart and are not useful in moving towards hope and collaboration.

An educational curriculum can play a significant role in constructing national identity and influencing the social and political views of citizens for generations. Learning about the reality of coexistence in Arab-Jewish history would break some contemporary nationalist stereotypes and build stronger relations between the people of the region and beyond.

Jewish life in North Africa and the Middle East may not have been perfect, but Jewish people thrived for generations and made countless contributions to their societies in these Muslim-majority regions. This is a history that, if rehabilitated by governments of the region, could potentially rekindle friendships and even a renaissance of historic coexistence.

Thank you to Kara Schoonmaker for exceptional support with the editing of this article, and to Dr. Liora Halperin, Dr. Sarah Zaides and Dr. Michael Laskier for their input on the subject.

Further Reading

- How Iraqi Jews are reclaiming their cultural legacy in Israel by Pablo Jairo Tutillo Maldonado (2018)

- My journey in Yiddishkeit: Learning Yiddish as an Arabic (& Judeo-Arabic) speaker by Mohamed Elias (2018)

Hi there, I share your interest in the expulsion of the Jews of Egypt in the mid-twentieth century personally, academically, and intellectually. Around the end of the nineteenth century, the municipal records of the town of Livorno were destroyed in a fire, and as a result, many Jews falsely claimed Italian citizenship, and there was really no one to say otherwise.

My understanding from family members is that Italian citizenship was relatively easy to obtain (at the right price), I think it’s really important to be careful how we tell this story because each person’s story of migration is different, as you correctly note.

You might consider contextualizing the story of migration with Sisi’s initiative to restore Jewish heritage sites countrywide earlier this year. The government began cleaning the slums in the Bassantine Jewish Cemetery in Cairo last month.

Very interesting. Thank you.

Right and wrong, the community was divided into two parts, the Egyptian (not really Egyptian) Jews with their foreign passports who had been in Egypt for only a few generations and the real native Jewish community who had lived in Egypt for thousands of years. The foreign Jews were in the main from Livorno and Jews from Aleppo and Baghdad plus a myriad of other places all of who kept their foreign passports. All of who in turn seem to have thought the real Egyptian Jews as beggars and not worth talking about. Much as the German Jews in America thought of the Eastern Sephardim