PC: Voice of Witness

I embarked on my graduate school journey with a passion for oral history and the conviction that it has the capacity to redefine the relationship between historians and the histories they write. In this spirit, historian Michael Frisch’s words have been central to my thinking about my work:

“[W]hat is most compelling about oral and public history is a capacity to redefine and redistribute intellectual authority, so that this might be shared more broadly in historical research and communication rather than continuing to serve as an instrument of power and hierarchy.” [1]

Throughout the process of its conceptualization, my dissertation project has focused on the intersection of Jewish Studies, oral history, and the exploration of life in East Berlin around the time of German reunification. Thanks to a Stroum Center for Jewish Studies Opportunity Grant that allowed me to attend the Voice of Witness Oral History Training in San Francisco in the summer of 2016, I was able to clarify how to best combine these three aspects in my work and evolved my dissertation into a multimedia doctoral project centered on the voices of East German Jewish women.

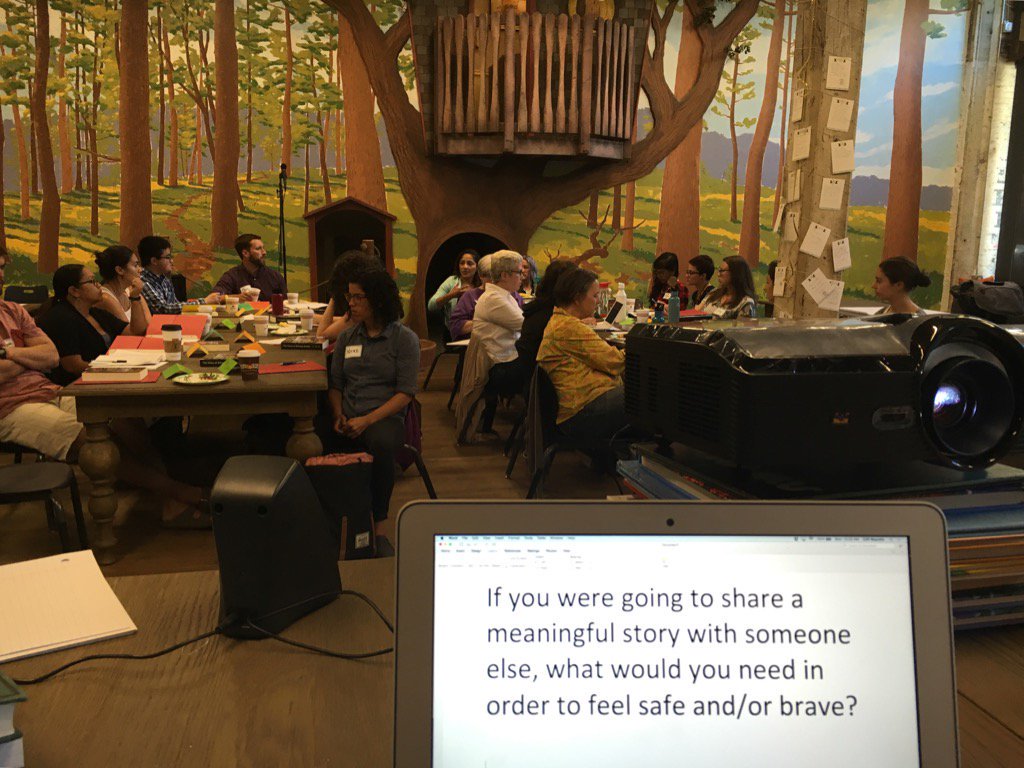

The week-long Voice of Witness Oral History Training is sponsored by Voice of Witness, an oral history non-profit founded by author Dave Eggers and writer and educator Mimi Lok that focuses on “amplifying unheard voices.” The training brings together oral history practitioners from across the United States with varying levels of experience with oral history. Participants ranged from researchers to educators. As someone who sees herself as equal parts researcher and educator, sharing the room with teachers who spoke about oral history as more than just a research practice was very enlightening for me.

As a result of the training, I began to understand how my academic pursuits might contribute to the amplification of my narrators’ voices. I began to ask myself: “What does it mean to be heard?” Many of the community members I spoke with during my time in Berlin in late 2016 (and others I plan to speak with later this year) have been vocal about their experiences as writers, actors, teachers, and scholars for decades. And yet, speaking and being heard (and even more so, understood), are often not the same thing. This is especially true in academic contexts and in politically charged conversations like those about the experience of reunification and individual narratives of life in the GDR (German Democratic Republic, a former name for East Germany). After all, the scarcity of these narratives in existing historical scholarship on Jewish life in the GDR was one of the reasons I decided to make them a central aspect of my own project.

During my participation in the Voice of Witness Oral History Training, I developed a clearer vision of how my academic project can make a meaningful intervention. The training encouraged me to think about the definition of “meaningful” or, more precisely, the question: Meaningful to whom? One of my dissertation’s goals is to amplify the narratives of East German Jews, and Jewish women in particular, living in Berlin during the late GDR period and the early reunification years in scholarly debates by highlighting existing scholarship and non-academic writing produced by community members as well as drawing on the oral history interviews I conducted. In my written dissertation I will thus explore topics such as Jewish identity across the 1989 divide and East German Jewish identities seen from the margins. However, my dissertation project will also include a digital oral history archive and exhibit and a curatorial concept for a physical exhibition, making my work accessible to a wider audience than just a handful of academics. Including oral history interviews is thus only one way in which I hope to redefine and redistribute intellectual authority as Michael Frisch describes it.

In addition to gaining a better idea of my project’s form and purpose, the Voice of Witness Oral History Training allowed me to refine my own practice through an in-class interview project, to think about ethical questions from a humanist rather than just a legal perspective, and to be inspired by the projects of presenters and fellow participants. These projects included Pendarvis Hershaw’s OG Told Me, an ongoing oral history project with African-American men in Oakland, and the oral history classroom project spearheaded by two teachers at Stagg High School in Chicago. The duration, scale, and creativity of these two and many other projects I learned about as part of the training serve as ongoing inspiration for my own work. And these lasting connections may be the most valuable takeaway from my Voice of Witness Oral History Training.

[1] Michael H. Frisch, A Shared Authority: Essays on the Craft and Meaning of Oral and Public History, SUNY Series in Oral and Public History (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), xx.