An Israeli military tank in the Golan Heights. Photo by Marwa Maziad.

By Marwa Maziad

There is no denying that Israel, despite being one of the few democracies in the Middle East, is a highly militaristic state. But does this stem from the military itself, or from within the civilian government and society?

There are a few different philosophies that have cropped up over the years to explain the relationship between the Israeli military and the government. Traditionalist thinkers like Dan Horowitz or Shmuel Noah Eisenstadt believe that civilian control has been clearly embedded since the inception of the state of Israel; therefore outright military coups have never threatened its political system.

The “critical approach” of analyzing Israeli civil-military relations, however, exemplified by Rebecca Schiff’s concordance theory, underscores the way Israeli society exhibits obvious militaristic characteristics, which defy any classically assumed “Western democratic” attributes.

Prominent civil-military relations scholar Yagil Levy describes the Israeli case as “civilian control over the military but not civilian control over militarization.” In my research, I found there to be three crucial elements in understanding Israeli military intervention in politics (sharing similarities with regional rivals Egypt and Turkey): governing, economic activities, and national security policies.

Military governing?

A train station. Israeli soldiers take public transportation, sit in cafes, and walk down the streets in uniform, a visible sign of Israeli militarism in public spaces. Photo by Marwa Maziad.

Regarding the question of military governing, while no outright coups have ever taken place in Israel, a long history of “parachuting” officers onto civilian political offices as a second career is a striking phenomenon.

“Civilianized” Yitzhak Rabin, Ehud Barak, Ariel Sharon are but a few of the former military generals who made it to the civilian office of politics. Although they have been democratically elected, the signs of militarized Israeli politics are also unquestionably apparent: the highest political office in the state becomes the continuation of a previous military career.

A poll taken in 2016 indicated that 93% of Israelis perceive the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) to be more trusted than the president (84%), the Supreme Court (64%), the police (59%) and the political parties (36%). It’s no wonder that former military officers have political clout. It follows that there could be a correlation between trust in the military as an institution and the subsequent rise and penetration of military men into politics.

Military in the economy

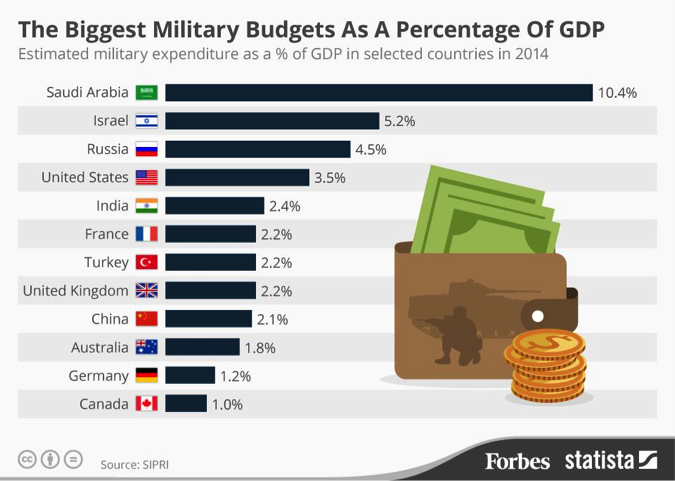

In terms of economic activities, the IDF are currently only exhibiting very early signs of economic undertakings, in light of societal pressures to cut their already high military budget — a budget that constitutes a disproportionately high 18% of the state budget, or up to 5.2% of GDP.

While Israel is not a NATO member, it is significant to compare its very high percentage of military spending to the lower spending of other Western countries that are members; the Trump administration is pushing nations to shoulder more of the financial burden and spend 2% of their GDP. Currently, on average, NATO members spend as little as 1.2% or less of GDP on their military.

Military spending, however, is directly related to threat perception. This emphasizes the need for a regional approach to understanding civil-military relations in a given case. That is because as Europe collectively reduced its military spending post-WWII, the Middle East has not uniformly eliminated regional threat perceptions.

Source: Niall McCarthy, Forbes.

If societal pressure succeeds in demanding military budget cuts, a new trend in Israel is that of the IDF evacuating its own lands and selling them to private investors. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Israel has needed to raise money from land bids in part because its military budget leaves little room for civilian spending.”

The money gained from evacuations of prime real estate locations in the heart of Tel Aviv — like the Sarona Mall, for example— is retained by the military, albeit operated by a separate budget, to be redirected towards new outposts in the Negev, or to other purposes deemed necessary by the military. It is thus telling that land in particular is an important military asset in Israel. Absent a huge military budget, the Israeli military might very well regularly use land assets as an income generator.

According to Amiram Oren’s article “Shadow Lands: The Use of Land Resources for Security Needs in Israel,” Israel’s security sector “controls and influences” more than 53% of the state’s territory, not even counting the military-occupied West Bank.

Oren emphasizes the significance and broader implications of the security sector’s penetration into the territorial realm. Israeli laws grant the security sector a distinct status beyond the civilian realm and allow it a broad spectrum of control. In the territorial domain in particular, Oren describes the security sector as functioning as if it were a “separate framework,” operating autonomously from the civilian spheres.

Scholars agree that the government, media, and civil society in Israel hardly pay attention to land use when it is for security reasons. This question of Israeli military land ownership has received insufficient attention, as reflected in the comparatively low number of concerns raised by academics, journalists and the general public in Israel.

For example, Shmuel Even, an expert on Israel Defense Studies at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv, said in an interview that the country’s defense budget of $15 billion in 2012 was constituted of “70 percent contributed by Israeli taxpayers, 21 percent coming from U.S. aid and 9 percent coming from Defense Ministry income.” My research asks: what is this “Defense Ministry income” and how exactly is this monitored?

Evacuated military posts that have made way for business development. Sarona Open Shopping Mall, at the center of Tel Aviv, stands on land previously belonging to the IDF HaKirya base. The General Staff Matcal Tower (with its helipad) is seen within the government, military, and business mixed-use complex. Photo by Marwa Maziad.

So far, direct military involvement in the economic realm might seem like a marginal activity for the Israeli Defense Forces (9% of the military budget). Nonetheless, the military has its impact on the broader concept of business and economic networks. Besides an actually established military-industrial complex of weapon manufacturing, there are even more subtle forms of militarism in the civilian market.

Dana Grosswirth Kachtan and Eve Binks, in their paper entitled “Converting social, cultural and symbolic capital and skills from military to the civilian society and labor market,” demonstrate that links formed during military service – and ties established among the top echelon of the military – continue after military service and impact one’s chances in the private business realm, and consequently one’s economic standing in society.

A case in point is the story of the Israeli startup WeWork, which joins Uber and Airbnb in being valued at $20 billion. Company founder and CEO Adam Neumann says his “kibbutz childhood and Israeli army service molded WeWork, nicknamed ‘Kibbutz 2.0.’” He attributes getting “to know a lot of my best friends” to his military service. One of those friends, Ariel Tiger, is currently the CFO of WeWork, and one of the company’s top managers. Thus, the way the Israeli military constitutes civilian business life is significant.

Military and national security policy-setting

When it comes to the national security advisory role, the IDF maintains a near monopoly over it.

In the work of Sheffer and Barak (2013), “Israel’s Security Networks,” the authors show that, particularly after the Israeli-Arab War of 1967 and the subsequent Israeli military occupation, a highly organic yet influential security network has impacted Israel’s domestic sphere. Composed of active duty and former security personnel and their partners in the state’s various civilian spheres, this security network has influenced Israeli culture, politics, society, public discourse, economy, and foreign relations.

Tank at “Ammunition Hill” dating back to the 1967 war, Jerusalem. Photo by Marwa Maziad.

Scholar Kobi Michael shows how contemporary “low intensity conflict” relates to military knowledge, thereby affecting civilian control — which is formally retained, as an ideal — at the institutional level, but in practice becomes weakened. Michael dissects Israel’s “epistemic authority” to reveal how the military elite dominates Palestinian affairs. The military is perceived as more trusted in these matters, both by the general public as well as by the civilian political elite. In turn, this situation impacts the way civilian control is practiced. Michael highlights the spectrum of political-military interaction and how it “reinforces the weakness of civilian control over the military” in Israel.

In conclusion, Israel is clearly militarized in all three dimensions of politics: governing, economic activities, and national security policies. It is clear that the militarization of the Israeli state and society is having an effect domestically. But this militarization of politics also impacts the region as a whole.

In a region currently threatened by the potential for total state collapse at the hands of a) proliferating militant non-state actors and/or b) renewed versions of old expansionist ideological turns, such as that of Turkey’s pan-Islamist Neo-Ottomanism and Iran’s Persian Revolutionary Islamism, we find that Egypt’s own militaristic turn since 2013, for example, was the outcome of regional tectonic changes. Egypt converged on Israel’s decades-long militarism, employing a similar rubric of a state fighting an “existential war” against external forces.

In the end, a perceived regional threat is a circumstance that directly impacts domestic civil-military relations and impedes orderly and balanced objective civilian control of the military— in countries throughout the region. What the long-term ramifications will be in the Middle East will only be known in the years to come.

Marwa Maziad is a PhD candidate in Interdisciplinary Near and Middle East Studies, with a focus on comparative civil-military relations and regional security studies. She is the recipient of the Israel Studies Research Scholarship from the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies at the Jackson School of International Studies. Findings from her dissertation “Oscillating Civil-Military Relations in the Middle East: Cases of Turkey, Egypt and Israel, A Dynamic Regional Order Approach” have been presented in a number of specialized conferences, such as the Association for Israel Studies (AIS); the European Research Group On Military And Society (ERGOMAS); the Inter-University Seminar on Armed Forces and Society (IUSAFS); the International Sociological Association Research Committee on Armed Forces and Conflict Resolution (ISA-RC01); and the Middle East Studies Association (MESA). Her regular commentary and analysis of Middle East Politics have been featured on BBC Arabic, Aljazeera English, CNN International, National Public Radio (NPR) and other Arab and international media. She can be reached at marwa@u.washington.edu and on Twitter @marwamaziad.

Marwa Maziad is a PhD candidate in Interdisciplinary Near and Middle East Studies, with a focus on comparative civil-military relations and regional security studies. She is the recipient of the Israel Studies Research Scholarship from the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies at the Jackson School of International Studies. Findings from her dissertation “Oscillating Civil-Military Relations in the Middle East: Cases of Turkey, Egypt and Israel, A Dynamic Regional Order Approach” have been presented in a number of specialized conferences, such as the Association for Israel Studies (AIS); the European Research Group On Military And Society (ERGOMAS); the Inter-University Seminar on Armed Forces and Society (IUSAFS); the International Sociological Association Research Committee on Armed Forces and Conflict Resolution (ISA-RC01); and the Middle East Studies Association (MESA). Her regular commentary and analysis of Middle East Politics have been featured on BBC Arabic, Aljazeera English, CNN International, National Public Radio (NPR) and other Arab and international media. She can be reached at marwa@u.washington.edu and on Twitter @marwamaziad.