After his coronation at Aachen, Emperor Heinrich VII affirms the privileges of the Jews of the Holy Roman Empire and their permission to live in his lands, circa 1340.

By Kerice Doten-Snitker

In November 2018, CNN released a disturbing report from their recent survey measuring the prevalence of anti-Semitic beliefs in Europe. While more than 40% of people agreed that anti-Semitism was a growing problem in their countries, more than a quarter thought Jewish people had too much influence in business and finance, and nearly 20% blamed anti-Semitism on the everyday behavior of Jewish people in their countries.

It’s obvious to scholars today that contemporary European anti-Semitism has nothing to do with Jewish people. Jews make up less than 2% of the population in any European state, so it’s a stretch to believe that Jews as a group have a significant influence, let alone too much influence, on business, media, or any other part of their fellow citizens’ daily lives.

Yet many academics and non-academics alike make the same mistake when looking back to medieval anti-Semitism, assuming a connection between medieval Jewish behavior and medieval anti-Semitic exclusion and violence. In fact, the balance of power between Christians and Jews was often so lopsided that Jews were peripheral to the central conflicts in medieval European society. Exclusion of Jews had more to do with conflict between Christians than between Christians and Jews.

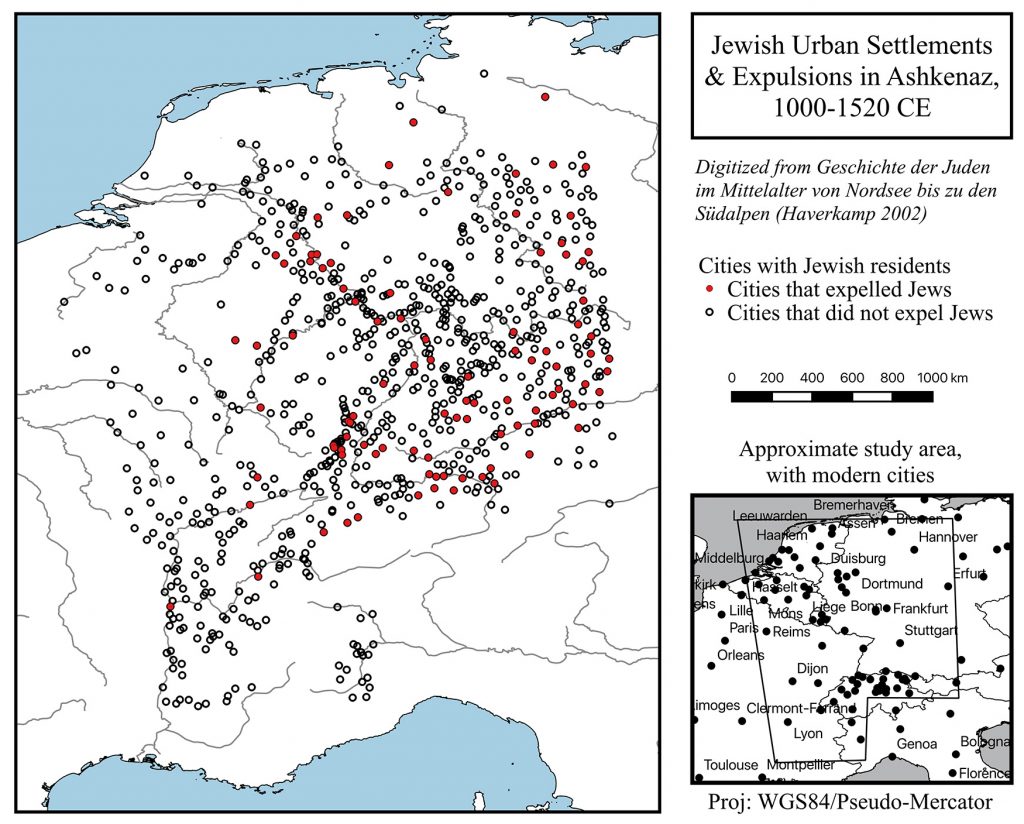

In my research, I argue that this was the case for Jews in German lands in the high and late medieval periods, 1000-1520 CE. These were the Jews of Ashkenaz, the historical region of Jewish settlement near the Rhine River and its tributaries, in the modern countries of the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, France, Switzerland, Austria, and Italy.

Jews in medieval Germany

A fruitful collaboration in the 20th century between German and Israeli historians produced “Germania Judaica,” a set of resources documenting Ashkenazi Jewish communities city by city, and its follow-up “Geschichte der Juden im Mittelalter von Nordsee bis zu Südalpen” (“History of the Jews in the Middle Ages from the North Sea to the Southern Alps”), a collection that includes a set of maps, an updated city-by-city catalog, and commentary. These resources are invaluable for understanding the regional history of Ashkenaz.

Map of Jewish settlement and expulsions in Ashkenaz, 1000-1520 CE. Created by Kerice Doten-Snitker.

The information recorded in these volumes shows that Jews migrated into German lands slowly in the ninth and twelfth centuries. First they settled in cities where Christian bishops were located, which were centers of religious and economic activity as well as some of the most established cities of the time. As medieval cities grew and became more numerous, so did the urban Ashkenazi Jewish population. The number of cities and towns with resident Jewish communities reached a height of 561 cities in the first half of the fourteenth century.

From the end of the fourteenth century on, urban life in German lands became more precarious for Jews. The threat of violence had been constant for Ashkenazi Jews in the Middle Ages. Urban Ashkenazi communities faced violence from brigades on their way to join the Crusades, local mobs, and roving mercenary groups.

But in the fourteenth century, cities also started to expel their Jewish residents, legally forcing them out through edicts from the cities’ governments. These fourteenth century expulsions were harbingers of political and religious changes that disrupted the relationship between Christians and Jews in the fifteenth century.

The underlying causes of expulsions

German urban expulsions of Jews became more common in the fifteenth century as part of parallel processes of territorialization and Christian religious reform.

Territorialization was the transitional process of political authorities attempting to establish sole dominion over specific territories; prior medieval forms of government were overlapping and did not have strict borders. At the same time, new and more prescriptive theocratic understandings of Christian piety revolutionized the relationship between rulers and their subjects by placing responsibility for community righteousness in the hands of rulers.

Together, these factors intensified political competition for legitimacy and control. Rulers and governments clashed over who had rights to which resources and whose authority mattered. Rights to govern and control Jewish residency and activities were subject to the same conflicts around exercising authority, bestowing privileges, and defining community membership.

Looking at the 1424 expulsion of Jews from Cologne

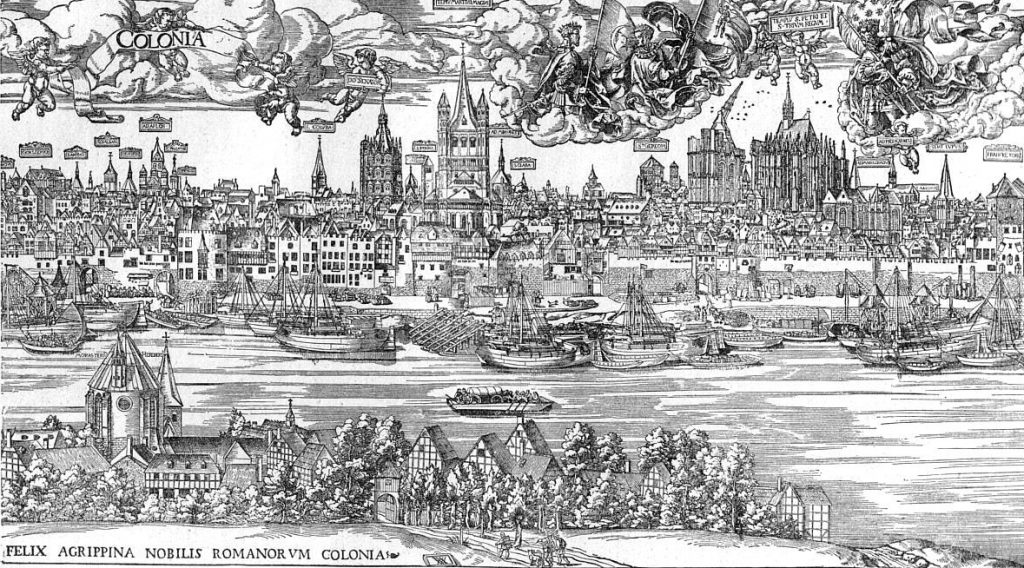

These dynamics played out in the expulsion of Jews from Cologne in 1424, as Markus Wenninger describes in his 1981 book “Man bedarf keiner Juden mehr” (“One cannot tolerate Jews anymore”), when the wealthy local elites of the city council and the Archbishop of Cologne were engaged in a fight over who held the highest authority in the city.

Woodcut of Cologne by Anton von Worms, 1531.

Archbishop Dietrich von Moes was angry that, instead of endorsing him against his rival, the city had remained neutral when he was first selected as a candidate for archbishop by regional political and religious elites. To demonstrate his power, the archbishop decided to take a stand on whether or not Jews would be allowed to live in the city.

Up to this time, the archbishop’s predecessor and the city government had had an agreement to share lordship and taxation rights over the Jews in Cologne. When the city tried to raise taxes without the consent of the new archbishop, von Moes took the city to the local court and was a force of continuing legal frustration until the council agreed to a mediation with him guided by a neighboring bishop.

The result of this mediation was that the city agreed to expel its Jewish residents, while the archbishop promised to provide a certain sum of money to the city government, which was in the middle of an economic downturn. The archbishop promptly settled the Jews in cities he had more direct control over.

The political roots of anti-Semitism

The expulsion of Jews from Cologne is one of the more well-documented expulsions in German lands. Clearly, it was a case where the issue at hand was not any activities or beliefs held by the city’s Jews. After all, the main instigator of the expulsion, the Archbishop of Cologne, did not mind that Jews lived under his dominion; he just wanted them under his sole dominion.

My research examines 118 expulsions across 814 cities. In these medieval cities, Ashkenazi Jews could not realistically initiate, sustain, or resolve episodes of violence; medieval Ashkenazi Jews should not be seen as responsible for the occurrence or dissipation of violence against them. Instead, the causes of violence against these Jews were located in the fault lines and factions that existed among Christians as they competed for power.

The same is true for contemporary anti-Semitic violence and exclusion in Europe and the US, and for violence and exclusion of other minority groups, like Muslims and Mexican-heritage immigrants.

Citizens of the US and Europe should beware the use stereotypes and fear-mongering to blame Jewish people or other minority groups and rationalize exclusion and violence. Politicians and governments that campaign and act to deprive and exclude minority groups like these do so when and where it helps them gain and maintain power and control.

Kerice Doten-Snitker is a doctoral candidate in sociology at the University of Washington. She double-majored in sociocultural studies and international relations at Bethel University (Minnesota) before completing an MA in sociology at the University of Washington. Her scholarly interests include processes of inclusion and exclusion in society. Her current work examines the roles of political institutions, economics, and religion in the exclusion of Jews in medieval times, focusing on the Rhineland (western Germany). In fall 2017 she was a visiting student at the Arye Maimon Institute for Jewish History at Universität Trier in Trier, Germany, funded by the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD). In addition, she works at the University’s Center for Evaluation and Research for STEM Equity, which focuses on increasing equity — and the participation of systematically excluded students and professionals — in the fields of science, technology, engineering and math.

Martin Luther’s “The jews and Their Lies”, is quite an eye opener to how strong anti-semitism was in Germany. I still hear Captain Mackey’s quoting Luther every time the subject of how the jewish people in Germany should be treated. The quotes were vulgar but directly from Martin Luther’s writings.

The Jews were subjected to many indignities but still, they lead the world in many ways