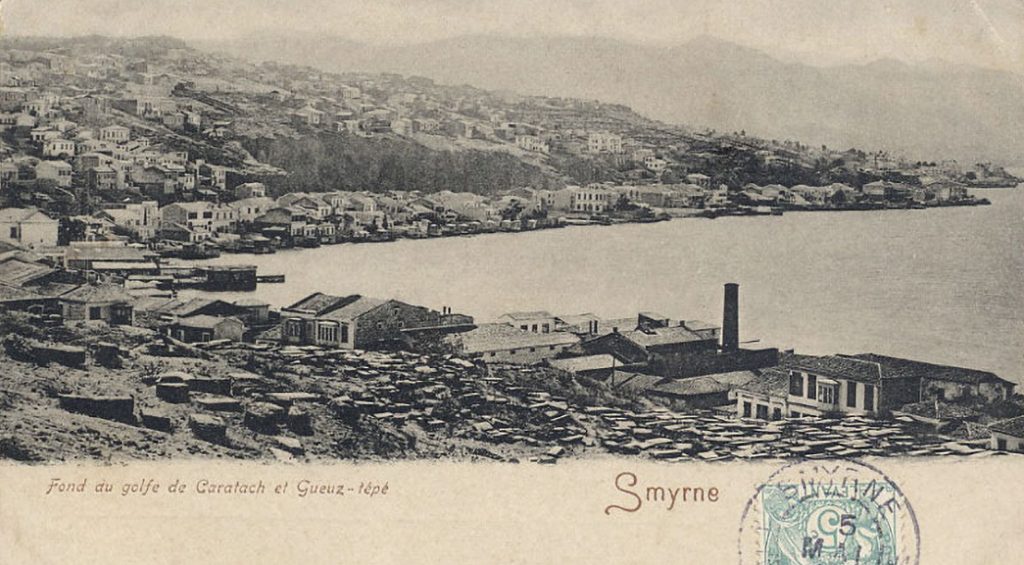

Early 20th-century postcard showing Izmir (also known as Smyrna; present-day Turkey). Via the Levantine Heritage Foundation.

By Canan Bolel

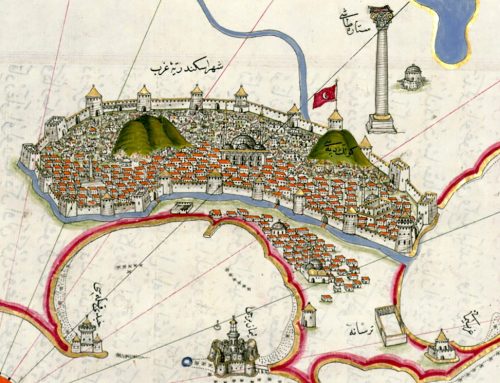

On March 13, on a Friday afternoon at the University of Washington’s Suzzallo Library, I was editing my dissertation chapter on the 1893 cholera epidemic and the Jewish community of Izmir, a major Ottoman port city famous for its figs and grapes, and also the city which I am a native of.

As I was eating my lunch, a bland tuna salad, it became clear that I would have to leave Seattle as soon as possible if I wanted to spend the rest of the COVID-19 pandemic with my family in Turkey, before further limits were put on international travel. I saved the last changes to the sixty-page Word document, finished my coffee, and headed back home to pack my stuff. I left Seattle 60 hours later.

I never expected that my research would connect so closely with my own reality. But now that we’re experiencing a global pandemic, I see unfortunate parallels between how Izmirli residents responded to the disease in nineteenth century and how people are responding today.

Researching the marginalized residents of Izmir, Turkey

For the last three years, I have been researching, reading, and writing on the poor, the diseased, the criminals, orphans, and religious converts of the Jewish community of Izmir (in present-day Turkey) for my dissertation, “Constructions of Jewish Modernity and Marginality in Izmir, 1860–1907.”

My research focuses on bodies and bodily experiences of individuals who did not fall within what was perceived as the “normal” in nineteenth-century Izmir. What was the “normal” of nineteenth-century Izmir? This is a difficult question, but, at the same time, it reveals the instability of the line dividing the normal and abnormal during the nineteenth century.

The marginalized people I met across the brittle pages of books in archives moved (relatively) freely within Izmir’s city center; were called names; hurt others or got hurt by the others; got caught and punished; or tricked the authorities and escaped.

Deciphering long-gone experiences of “particular Jews” of Izmir reveals Ottoman Jewish understandings of communal identity and modernity, especially during periods of crisis, such as intracommunal fights between the rich and the poor, perceived threats to the physical and moral unity of the community from Christian missionaries, or a rise in criminal activities.

During these periods of crisis, survival in the face of perceived threats shaped the social and political setting of communal life. Epidemics were some of these “difficult times.”

Epidemics in 19th-century Izmir

My dissertation’s first chapter, “Diseased Jewish Bodies, Diseased Jewish Spaces,” focuses on the 1893 cholera epidemic in Izmir (also known as Smyrna, in present-day Turkey) and the experiences of the city’s Jewish residents. Focusing on the removal of disease-stricken lower-class residents to the outskirts of the city by local authorities, and the similar treatment of newly arrived Jewish immigrants from Russia by Jewish community leaders, reveals how diseased bodies were understood and dealt with in the society.

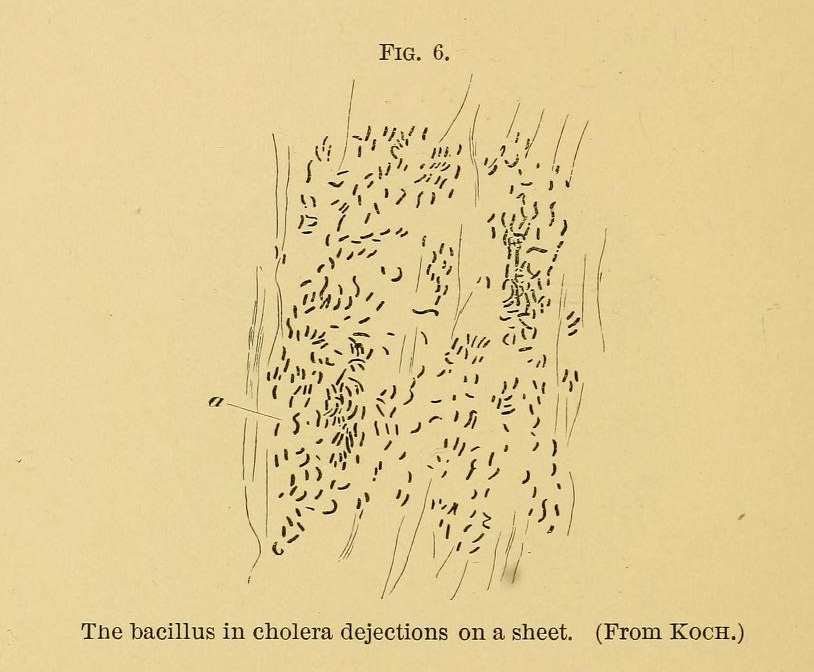

Illustration of cholera bacillus bacteria from the 1893 medical text “Cholera : its causes, symptoms, pathology and treatment.” Via the Internet Archive.

A diarrheal disease, cholera struck Izmir nearly every ten years throughout the nineteenth century, with devastating results, especially in the years 1831, 1865, and 1893. Cholera spread rapidly in the city, especially in overcrowded locations with poor access to sanitation and clean water. People became infected after digesting food or water contaminated by the cholera bacterium.

By the late nineteenth century, sanitation and medical officials of the time had identified a direct correlation between cholera and overcrowding in dwellings, which led to the portrayal of low-income members of the Izmiri Jewish community — who resided in overcrowded dwellings — as the original source and disseminators of cholera to the rest of the city.

The 1893 cholera epidemic in particular, one of the worst epidemics in nineteenth-century Izmir, left its mark on the collective memory of the residents of this eastern Mediterranean port city, culminating in a riot where poor residents of the city plundered bakeries.

My research on the 1893 cholera epidemic relies on Ottoman official documents, medical and sanitation reports, and articles from the local Turkish and Ladino press. It reveals two things: depending on their class, individuals had very different experiences of cholera; and, particular groups were blamed as the original sources or as transmitters of the disease, or both.

Lesson #1: Vulnerability to disease corresponds with a lack of resources

First, the fear and ambiguity surrounding cholera in Izmir led people to escape the city for the surrounding villages, contributing to the spread of the infection to the hinterland. During an earlier cholera epidemic in 1865, only the dying and the dead had been left behind as other residents fled. In the ghost city, dead bodies piled upon one another as there wasn’t anyone to take care of the dead.

Although flight was the typical response, how the days in the refuge were spent depended heavily on the resources of the individual—in other words, one’s wealth, or lack of it. Wealth determined whether an individual would be spending the following months sleeping under a tree with limited food or in a summer house with the perfect view of the Aegean Sea.

In a similar way, today, the super-rich have turned to private jets to escape coronavirus, taking their personal doctors and nurses with them as they travel to their holiday homes. Some of them have also paid for the construction of underground shelters for their families.

Lesson #2: Outsiders are blamed for the illness

Second, during the cholera epidemic of 1893, particular groups were blamed for the emergence of cholera, and later, its spread to the rest of the city. In this regard, overcrowded lower-class Jewish quarters were put under scrutiny by public health authorities and other local authorities, which led to their inhabitants’ forced removal to the outskirts of the city. Similarly, Jewish community leaders singled out the newly arrived immigrants from Russia escaping pogroms as contributors to the disease and sought ways to segregate them in a place distant from the Jewish community in newly constructed barakas (sheds).

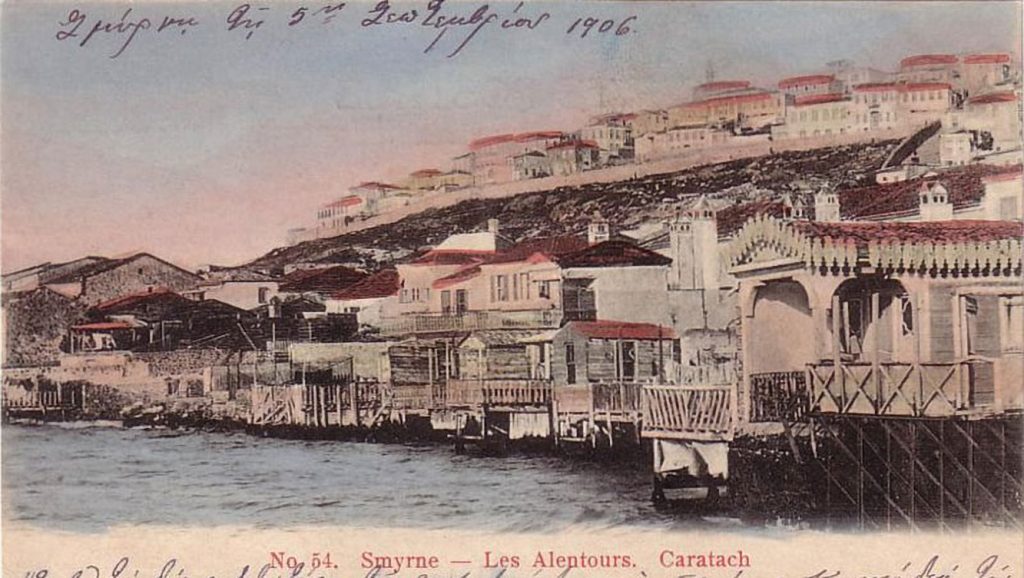

1906 postcard showing the Karataş neighborhood of Izmir. Via the Levantine Heritage Foundation.

Jewish residents’ suspected role in cholera led to a fight in the pages of the local Ladino and Greek-language press in 1893. Yet, the war of words was not limited to the pages of newspapers. The local Greek press’s portrayal of Jews as the originating source and also as transmitters of cholera, led to the beating of a Jewish peddler while he was crossing the Greek quarter of the city in 1893.

During another cholera epidemic in 1898, even upper-class members of the Jewish community took their share of this resentment: Regular Jewish customers of fancy cafes along a waterfront promenade owned by Greeks were harassed and given higher prices. One of the Greek cafe owners even approached a Jewish customer and told him that fellow Greeks had ordered him to triple the prices of the drinks only for his Jewish customers. The objective was to discourage a Jewish clientele. Izmir’s municipal court condemned the owner of the cafe to a day in prison and a fine of 50 francs.

How does the dividing line between a disease and an individual disappear? When do people start to embody a virus or a bacterium, a walking microorganism, a microbe in the eyes of others? If the Jewish body was perceived in the image of the disease it was associated with during the summer of 1893, was a peddler’s beating a manifestation of locals’ fight against cholera, with kicks and punches? When café owners wanted to discourage Jewish clients, were they in fact preventing the spread of the cholera bacterium?

Echoes of the past in the present pandemic

I realized that things were changing in January 2020 when I decided to have lunch at my favorite restaurant in Seattle’s Chinatown-International District. I ate my food — sweet and sour chicken with broccoli — in total silence as I watched the nearly empty bubble tea shop across the street. The situation got worse in the following weeks, as Asian businesses continued to lose customers. Before mandated closures and stay-at-home orders, some people had started avoiding other people, particular places.

Coronavirus-related racism, xenophobia, and stigmatization were (and still are) everywhere. In February of 2020, Turkish media outlets shared the video of a young man in Istanbul and his LED-pixelized backpack. On his backpack was written “I’m NOT Chinese,” both in English and Turkish, followed by “Ben Tayvanlıyım (I’m Taiwanese).” His video was shared as a “funny” news story by Turkish news media to lighten the mood amid coronavirus-related fear and stress. Soon afterwards he appeared on a late-night talk show.

Coronavirus-related racism, xenophobia, and stigmatization were (and still are) everywhere. In February of 2020, Turkish media outlets shared the video of a young man in Istanbul and his LED-pixelized backpack. On his backpack was written “I’m NOT Chinese,” both in English and Turkish, followed by “Ben Tayvanlıyım (I’m Taiwanese).” His video was shared as a “funny” news story by Turkish news media to lighten the mood amid coronavirus-related fear and stress. Soon afterwards he appeared on a late-night talk show.

That individual, Tsai Yen-chen, a 22-year-old graduate of Turkish language, was visiting Turkey to find a job. In fluent Turkish, he said that in Ankara people had run away from him screaming. In Istanbul, taxi drivers refused to pick him up. Offended by people’s reactions, he decided to wear this backpack with the pixellated phrases on it. Throughout the show, “jokes” about his Asian identity and rosy cheeks (see, signs of high fever) were made repeatedly. He was asked if Taiwan is close to China. He was asked if he had fever. Towards the end, the host said, “Not every Chinese, every slant-eyed is sick.” A couple of minutes later the host asked him to put the name of the talk show on his backpack’s LED display, encouraging him to do this for a week as he was looking for a job. On camera, Tsai Yen-chen put the name of the show on his backpack. Everyone applauded. The backpack was made in China.

There are many similarities across space and time in responses given to outbreaks of deadly diseases, as the fear of the unknown remains at the middle of everything, unmoving. The same forces at play in historic Izmir are at play in the present, too: resources and privilege impact vulnerability, and fear of the other as an embodiment of the disease is unfortunately common.

As a social historian who traces the course of a 126-year-old epidemic, I wonder, how are we (and the next generations) going to remember, and talk about, the COVID-19 pandemic?

I do not have an answer yet.

Canan Bolel is a doctoral candidate in Near and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Washington. Her dissertation project, “Constructions of Jewish Modernity and Marginality in Izmir, 1860–1907,” focuses on embodied marginalities, and questions how Ottoman Jews constituted their identities within imperial and communal settings by focusing on the Jewish diseased, criminal, and converts to Christianity of Izmir. She is currently a doctoral fellow at the Posen Society of Fellows and the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies of the University of Washington.

Canan Bolel is a doctoral candidate in Near and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Washington. Her dissertation project, “Constructions of Jewish Modernity and Marginality in Izmir, 1860–1907,” focuses on embodied marginalities, and questions how Ottoman Jews constituted their identities within imperial and communal settings by focusing on the Jewish diseased, criminal, and converts to Christianity of Izmir. She is currently a doctoral fellow at the Posen Society of Fellows and the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies of the University of Washington.

Leave A Comment