The Olympians receiving Psyche. Ceiling fresco by Raphael at the Villa Farnesina, Rome. Ca. 1518.

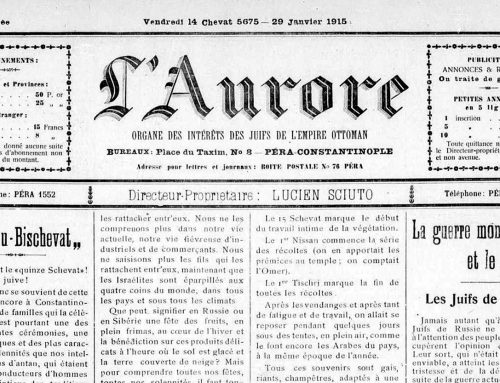

Session 1 of the Stroum Center’s Community Learning Fellowship (CLF) ~ Jan. 14, 2015

ἀλλ’ εἰ χεῖρας ἔχον βόες ⟨ἵπποι τ’⟩ ἠὲ λέοντες,

ἢ γράψαι χείρεσσι καὶ ἔργα τέλειν ἅπερ ἄνδρες,

ἵπποι μὲν θ’ ἵπποισι βοὲς δέ τε βουσὶν ὁμοίας,

καί ⟨κε⟩ θεῶν ἰδέας ἔγραφον καί σώματ’ ἐποίουν

τοιαῦθ’ οἷόν περ καὐτοὶ δέμας εἶχον ⟨ἕκαστοι⟩.

Xenophanes of Colophon, Fr. 15

But if oxen and <horses> and lions had hands,

And could draw with their hands, and do the works of men,

Horses would draw the forms of their gods like horses,

And oxen like oxen, and they would make their bodies

Such as they each had themselves.

In the weeks since the Community Learning Fellowship class I led in mid-January, I have found myself twice in nearly identical, and nearly identically frustrating, conversations—with nearly identical strangers. The conversations were incidental, but each concerned how to read the ‘Bible’ (though in each case my interlocutors actually meant “the Torah,” and most specifically “a few passages of Bereshit”) and, more broadly, how to contextualize ancient Judaism and Christianity within the highly complex world of ancient Mediterranean myth, religion, philosophy, and literature. I spend a great deal of time in this world, and being a teacher by trade, and a fool by practice, I figured it wouldn’t hurt to try to help.

The conversations, as I note above, took a nearly identical course (and it was not a good one). My interlocutors, as I note above, were also nearly identical, in that they both proved to be Biblical literalists. But they differed in the detail that the first was a Strong Atheist (for whom the strong belief in the inexistence of gods is based on a literal reading of the Biblical texts), and the second an Evangelical Christian (for whom the strong belief in the existence of the Christian god is based on a literal reading of the Biblical texts). What I found both astonishing and frustrating was that these two argued—one for the “absurdity” of religion, the other for biblical infallibility—under precisely the same set of assumptions: that Biblical texts are intended to be—and so should be viewed as—historical documents. And, as historical documents, they may be proven, or disproven, solving all the world’s problems, once and for all. Selah.

But I am not a Biblical literalist: I am a Classicist, a social historian, a philologist, and a literary scholar. And so in the course of each of these conversations, I tried to explain what I know about the use of metaphor and analogy in ancient texts; I explained that myths may posses a ‘vital human truth’ without having a drop of ‘historical accuracy’ (a point we began with at my January CLF class—it’s an important point, and one too little recognized, I think); I spoke of the deep humanity of religion—religious ritual appears pretty much everywhere people do, from as early as we can trace them; I pointed out that the notion of ‘belief’ in a god is not one we see expressed in the Torah or indeed any pre-Christian Greek or Roman texts. And in each conversation, at one point, and deeply exasperated, I quoted the Xenophanes, above—

“But if oxen and <horses> and lions had hands,

And could draw with their hands, and do the works of men…”

To be fair, this happens to be one of all-time favorite quotes, and as a result I try to slip it into nearly every conversation I have. The point of the quote—that we all create our gods in our own images—is an important one. It’s a point I tend to agree with—and one we discussed early in our CLF seminar, to great effect—and one that, I think, is valuable in its ability to recast inquiry into Biblical (and indeed classical) texts. For when we consider these to be texts that may contain humans truths that exist independently of historical fact, we can move from “Did this happen, or didn’t it? Let’s settle this once and for all” to “What can I learn about the people who wrote this? Why write a god (or gods) this way? What questions are they asking of themselves and the world they live in? Who were they? (And so, by extension, who are we?)”

Looking at Bereshit and Theogony

These are the questions we discussed during my January CLF seminar—and I found the discussion a lively, engaging, and occasionally challenging one (I admit to enjoying discussions more when I am challenged by them myself). After we considered Xenophanes’ 6th-century BCE musings on the nature of the gods (in short, he rejects Homeric polytheism, notes that different peoples create different gods, and finally posits that “G-d is One; the greatest among gods and men / like mortals neither in body nor in thought” Fr. 23), we turned to a close reading of Bereshit 1-3, investigating what we might make of the worldview that is presented in these paired creations. The ‘first’ creation, Bereshit 1.1-2.4, presents—upon close reading—a surprisingly stable, orderly, rational worldview. It seems to suggest a people deeply interested in the origins of the universe, of their world, of everything in within this world, with increasingly complexity and differentiation. It is a world in which language is powerful, and speech creates. It is a world that is constructed through continuous separation and differentiation (in some ways this reads much like early Presocratic inquiry), and one that is advanced through ongoing aesthetic (“it is good”) and ethical judgment.

After a quick jump to Bereshit 2.5 and following—where we see a very different representation of the Hebrew god, this time as a caring, protective parental figure again interested in the ethical maturation (Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil) of the offspring—we turned finally to about twenty lines of Hesiod’s Theogony, a 7th-century BCE epic poem that is responsible for most of what people think about when they think about “Greek creation myths.” In this text, the product of one of those “rational Greeks,” we see a worldview entirely at odds with that presented in Bereshit. Although there is some effort to present a universe that evolves in complexity (we begin with Chaos, the Yawning Void, and move quickly to the creation of sky and earth), the Theogony presents a world without an organizing divine principle, one in which material production is achieved through sexual reproduction, a reproduction so unmanageable that it can be stopped only through violence. It is a world in which the gods are in constant strife with each other, engaging in the sort of scheming, stalking, gossip and character assassination that would do Twitter proud. It is—for a good while, in fact—a world blissfully devoid of human beings, and one in which human beings would do best to steer clear of the gods they have created for themselves (as I tell the students in my myth classes: “You don’t want a personal relationship with a Greek god. If you see a Greek god, you are about to be killed or impregnated”). It is a world in which one suspects that humans were created primarily as props in the ongoing drama of Gods Behaving Badly. It is a world that arose in close geographic and temporal proximity to the world of Bereshit, but it is also a world away.

It is with these observations that our seminar ended. I don’t expect that we really answered any questions about the earliest depictions of the Hebrew god—that was not my goal, and such is quite frankly outside my areas of expertise—but we did dip our feet into what I’ve always found not merely an important and productive way of approaching ancient texts, but one that allows us to wrestle with texts without ridiculing or belittling them.

For I’m with Xenophanes here: I suspect that people do create their gods—and their myths—in their own image. And so in examining such creations critically and respectfully, we may not merely learn more about our intellectual and cultural forebears—we may learn more about ourselves.

Links for Further Exploration

- Community Learning Fellowship page

- “The Myth of Tradition” – JewDub Talk by Prof. Sarah Stroup (2012)

- Digging for the Past, Looking to the Future – Profile of Prof. Sarah Stroup and the Tel Dor Field School (Sep. 2012)

- Opening the Floodgates – blog post by Prof. Sarah Stroup (Sep. 2012)

Leave A Comment