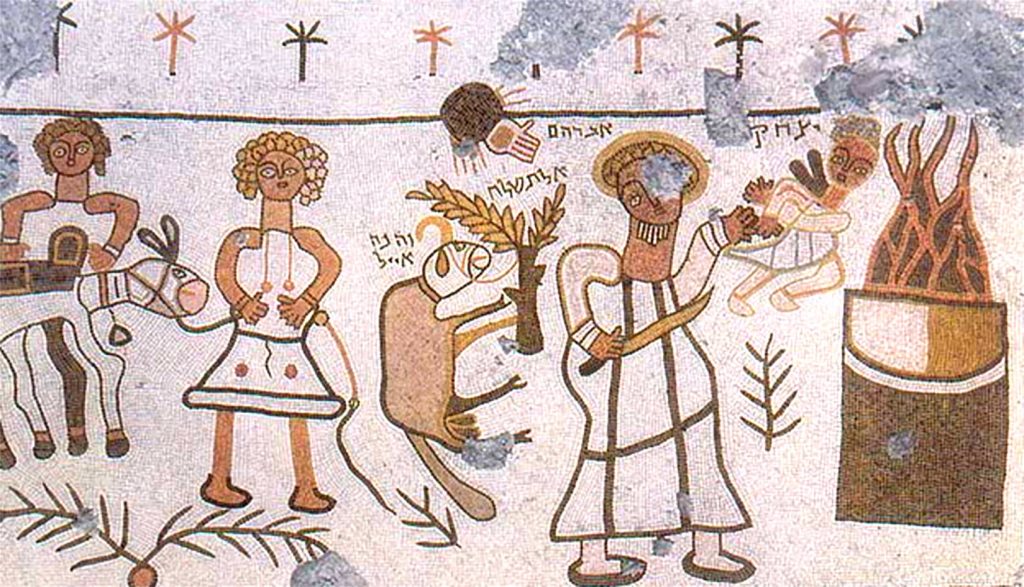

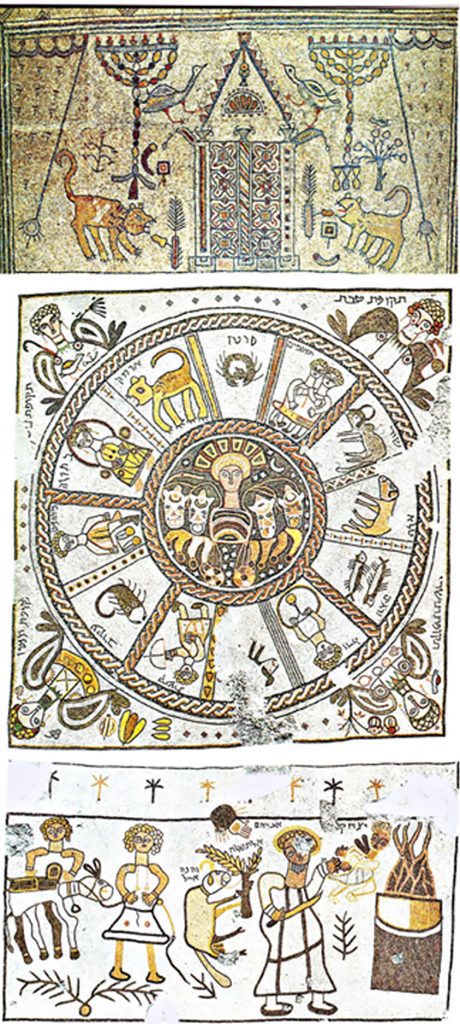

Detail from a 6th-century CE synagogue mosaic showing the story of Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac

By Abby Massarano

There is a perception in some religious and scholarly circles that ancient Judaism was strictly aniconic — that is, lacking images of human figures in art and design. Not only is this false, it often carries with it supersessionist undertones, with some writers arguing that Jewish aniconism was a sign of Judaism’s supposed primitive, precursory status as a religion.

The Birds’ Head Haggadah, c. 1300, is a German Ashkenazi illuminated manuscript currently at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Not all ancient Jewish communities were aniconic. Figural art — art that depicts people and animals — has been found throughout Jewish history in numerous settings, from ancient burial sites to medieval manuscripts, and seems to have played a significant part in how some Jewish communities engaged with their sacred spaces and religious practices.

Dedicatory inscriptions found in several synagogues all over the Levant — the eastern Mediterranean region encompassing modern-day Syria, Israel, and Jordan — tell of congregant donations funding synagogue art and décor. Visual imagery from neighboring and ruling polytheistic societies such as those of Greece and Rome are interwoven with identifiably Jewish symbols. There is no doubt that these works of Jewish art held significant religious and civic value.

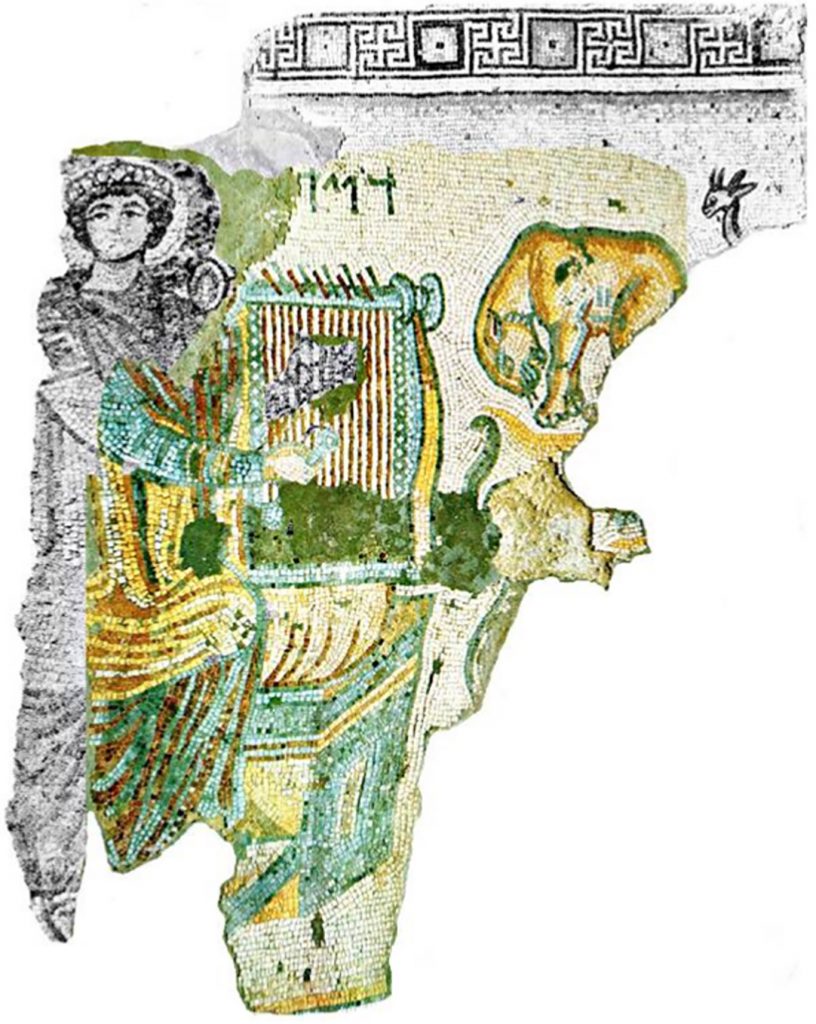

King David, as identified by his name written in Hebrew, is portrayed on a late antique Gaza synagogue floor mosaic as the Greek poet and musician Orpheus. His pose, clothing style, and act of playing the stringed instrument are iconographic elements distinctly associated with this pagan character.

In my current research, I explore this notion of civic and religious engagement in ancient Jewish communities through the use of figural art. I analyze how three Late Antique synagogues, active in the period from around the 2nd to 8th century CE, used and interacted with depictions of one biblical narrative taken from the Torah, Akedat Yitzchak (shortened to Akedah), or the Binding of Isaac, the story of Abraham’s attempted sacrifice of his son Isaac and God’s intervention.

Each of the synagogues, found at Dura-Europos (in present-day Syria) and Sepphoris and Beit Alpha (in present-day Israel), display versions of the Akedah that include commonly used visual tropes found in Akedah scenes throughout the Levant, North Africa, and Europe in both Jewish and Christian Late Antique settings.

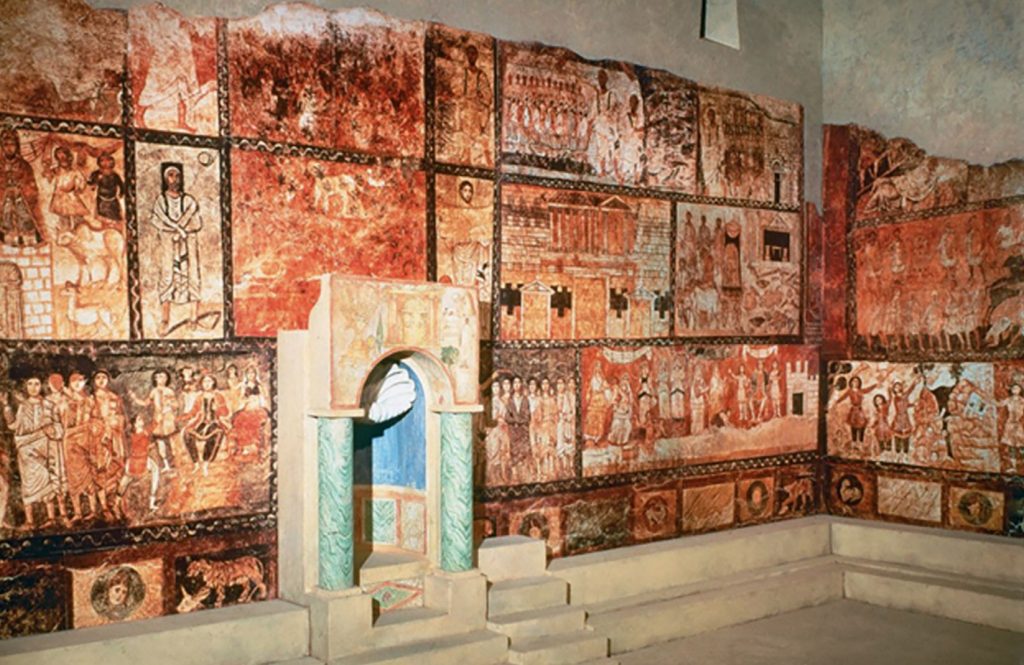

The walls of the main assembly room in the 3rd-century synagogue at Dura-Europos were covered with vibrant frescoes of important Jewish figures, biblical stories, and historical events. The Akedah is depicted on the top right of the Torah niche. The frescoes were reconstructed in the National Museum of Damascus in Syria.

While there is plenty to discuss for all three of these synagogues, I will focus on the example found at Beit Alpha and its use of Hebrew quotes from the Torah within the image.

Depictions of the Akedah

The Akedah, found in Genesis chapter 22, verses 1 through 19, is one of the paramount scenes in Judaism, and is likewise important in both Christianity and Islam, though for very different reasons. Abraham is told by God to sacrifice his son Isaac. He takes Isaac to the designated site, sets up a sacrificial altar, and binds Isaac’s hands. As Abraham has the knife raised and is ready to strike, a messenger, or angel, of God stops him. Abraham has proven his devotion to God and sacrifices a nearby ram tangled in a thicket instead. In Judaism, this is the moment where Abraham proves his faith in God – where, because of this faith, his descendants would be blessed.

The majority of visual depictions of the Akedah – in both Jewish and Christian Late Antique contexts – consistently portray several key narrative elements of the story, though visual interpretations vary based on community context and differing religious commentary on the biblical text.

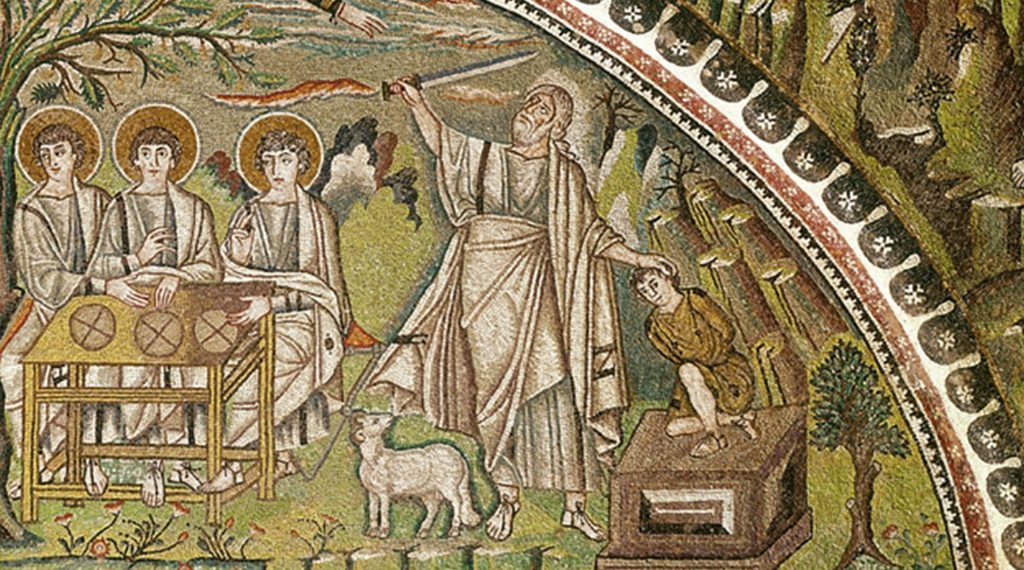

This Christian version of the Akedah in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy was created around the same time as Beit Alpha and displays many of the same tropes, including the Hand of God. However, there are distinctions here, such as the ram at Abraham’s feet, tugging on his robe, instead of near the tree.

Abraham and Isaac are always present, though their appearances and ages vary. Most depictions also include an altar, Abraham holding a weapon, and the Hand of God in the sky — a common visual stand-in for God at this point in history – in place of the messenger or angel.

On the left, a 4th-century coin depicting Constantine being crowned by the Hand of God. On the right, a fresco at Dura-Europos of Moses at the burning bush talking with the Hand of God.

The ram and the thicket are often present, and some depictions include two young men and a donkey, who are mentioned earlier in the chapter as the two other people Abraham took along for the journey.

The Akedah in the Beit Alpha synagogue

With this background on the Akedah narrative and its common visual tropes, we can examine the version at Beit Alpha, a sixth-century synagogue in modern-day northern Israel. On its floor is a large mosaic, likely completed sometime between 518 and 527 CE, which includes significant figural imagery as well as dedicatory inscriptions in Aramaic and Greek. These inscriptions identify the artists, and state that the mosaic was funded by the community as a whole.

The main part of the floor mosaic is separated into three panels. Closest to the entrance of the synagogue is the scene from the Akedah, followed in the center of the floor by the zodiac and four seasons surrounding a sun god, and finally, a depiction of the Torah ark, where the Torah scrolls were kept, surrounded by various animals and significant Jewish symbols, such as menorahs and shofar horns, on either side of the ark.

This Akedah scene was likely meant to be “read” from right to left, as is conventional for reading Hebrew. Accordingly, starting from the right, we see a flaming altar with a young Isaac hovering above it, his hands bound in front of him. Abraham stands to the left of the altar, grabbing at Isaac’s bound hands. A knife is held in his right hand, pointing directly toward Isaac. Abraham is staring upward to the Hand of God at the top center of the panel, underneath which is the ram tied to a tree. On the left of the panel stand the two young men and the donkey, positioned at a distance from the main action of the scene. There is very little background imagery to indicate setting — only a few branches strewn throughout the panel and a decorative row of palm trees at the top.

What is curious here are the four Hebrew inscriptions within the image. From right to left, they read Yitzhak, Avraham, al tishlakh, and v’hineh ayil, which respectively translate to Isaac, Abraham, Do not stretch out [your hand], and Here is a ram, the last two being quotes from the Torah. While it was not uncommon to include Hebrew within synagogue floor mosaics to identify objects or characters, the inclusion of direct Hebrew quotes from the Torah within the Akedah narrative seen here is unique to Beit Alpha.

To note: The Hebrew language was not historically used as a spoken language in daily life, instead serving a religious purpose. In fact, the vast majority of Jews in this region would not have been able to actually read Hebrew script at this time. They would have known the narratives of Torah and other biblical writings mostly through contemporary oral traditions, such as liturgical poetry – some of which focuses on the Akedah – and weekly oral readings from the Torah scroll.

On top of that, due to the prominence and conventional nature of these visual tropes throughout the Late Antique Jewish and Christian communities it is likely that people would have recognized the events of the narrative from the visual elements alone.

So why are the inscriptions here? What was the purpose of including direct, textually accurate quotes from the Torah within the visual imagery if so few people could read it? How was the community meant to engage with this scene?

While there are several other possibilities, I argue in my research that the placement of the direct quotations was meant to act as a prompt for members of the community to reflect on, or actively engage with, the Akedah narrative and its significance as they entered into this sacred space.

The physical placement of the sacred words in the center of the scene may have signified the exact moment when God acknowledges Abraham’s devotion, drawing the eye to the pinnacle of the story, and emphasizing the narrative’s significance. In addition, the Hebrew quotations may have acted as glyphs, where their overall meaning of the text was known by viewers, if not the individual letters, and these may have held religious power for the viewer.

Connecting with Judaism and community through art

Each depiction of the Akedah stands by itself as a nuanced form of biblical and social commentary, a record of how its commissioning community (Jewish and otherwise) understood the significance of the narrative.

Beit Alpha and its counterparts at Dura-Europos and Sepphoris, in their use of figural art, speak to a deep engagement in the religious and civic life of some Late Antique Jewish communities that complicates assumptions of a “visually restricted” Judaism. Not only do the dedicatory inscriptions within the visual décor speak to the communities’ deep connection to the synagogues themselves, but also to an active interest in having this type of art within their sacred spaces. Further, the use of Hebrew quotations within the narrative art at Beit Alpha demonstrates the congregation’s connection to the words of Torah and to their religious history, in the form of the story of Abraham and Isaac.

Judaism has never been completely aniconic. Jewish art reflects the constant evolution and forward movement of Jewish communities, past, present, and future.

Abby Massarano is a graduate student in the School of Art, Art History, and Design at the University of Washington, where she is pursuing her M.A. in art history. Her research is focused on the interplay of image and biblical text in Mediterranean and Near Eastern Abrahamic art in Late Antiquity. She received her B.A in psychology with a minor in art history from Mills College in Oakland, CA. After moving to Seattle, she worked in art conservation and preservation before deciding to return to academia. For her fellowship project, Abby is researching the interplay of text and image in late antique Abrahamic art of the Near East and the Mediterranean through scenes of the Akedah (The Binding of Isaac) in synagogues and other worship spaces. In addition to the Stroum Center graduate fellowship, Abby is also a recipient of the Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship for Hebrew.

Abby Massarano is a graduate student in the School of Art, Art History, and Design at the University of Washington, where she is pursuing her M.A. in art history. Her research is focused on the interplay of image and biblical text in Mediterranean and Near Eastern Abrahamic art in Late Antiquity. She received her B.A in psychology with a minor in art history from Mills College in Oakland, CA. After moving to Seattle, she worked in art conservation and preservation before deciding to return to academia. For her fellowship project, Abby is researching the interplay of text and image in late antique Abrahamic art of the Near East and the Mediterranean through scenes of the Akedah (The Binding of Isaac) in synagogues and other worship spaces. In addition to the Stroum Center graduate fellowship, Abby is also a recipient of the Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship for Hebrew.

Beautifully written Abbey…….

Thank you