By Michael Rosenthal

Most citizens of the United States, especially those who belong to religious minorities, like the Jews, believe that religious tolerance is a central value of our liberal society. But what exactly does it mean, and what are the limits of tolerance? Recent debates over the immigration of Muslims to our country have put these questions at the forefront yet again. Philosophers can help us understand both the nature and the extent of tolerance.

The legal basis of religious tolerance is at the heart of our system of government. The First Amendment of the US Constitution states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…” The fact that this is the very first line of the Bill of Rights shows that our Founders thought it was of the utmost importance to ensure that there would not be an official (i.e., an ‘established’) church and that the government would not use its coercive powers to interfere with the practice of different religions. The First Amendment guarantee of religious freedom is the cornerstone of our practice of toleration.

The authors of this document were certainly influenced by their recent past. They were not that distant in time from the Wars of Religion that had plagued Europe after the Reformation, and they had seen how government interference in religious life led to conflict and instability. The authors of the First Amendment have also influenced—whether they intended to or not—how we think of tolerance more broadly. As the recent history of the culture wars over homosexuality shows, many of our fellow citizens believe that the liberal society is one in which we tolerate not only beliefs but also practices or lifestyles. However, the more offensive or controversial the speech or the ‘lifestyle,’ the more likely that the words or practices will be deemed ‘intolerable’—that is, something that cannot be accepted. Hence, many debates about toleration also raise questions about the limits of toleration. Are there beliefs or practices that ought not to be tolerated?

The fact is that what it means to tolerate something—not only its legal basis but also its moral justification—is something that we are (or ought to be) always discussing in a liberal society. And philosophy is essential to that discussion. When authoritarian governments tried to impose religious beliefs on their citizens in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, philosophers explained why this was both impractical and unethical. They helped conceive of new political mechanisms—like the social contract—that helped resolve conflicts democratically. It should not surprise us, then, that the Founders were deeply influenced by philosophers like Locke and Voltaire who had written treatises on toleration.

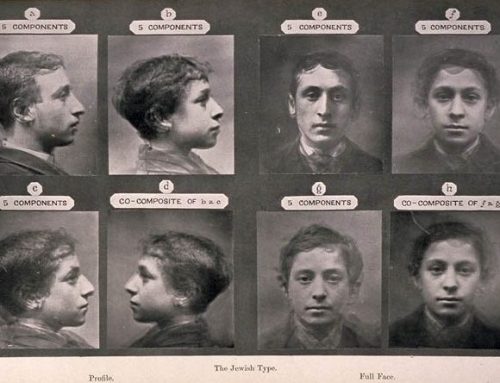

Spinoza’s 17th-century ideas of tolerance helped to shape modern society. How are these ideals being challenged today? Art by Bøger.

My research on the history of political philosophy focuses on a seventeenth-century thinker, Baruch Spinoza, who was a victim of intolerance and became the advocate of a new idea of tolerance that shaped modern society. Spinoza defined a new relation of church to state, one in which there was a broader scope of religious expression and practice than before. He provided a rational critique of religion, which eventually helped loosen the church’s grip on earthly power. Although Spinoza was ultimately expelled from the Jewish community for his unorthodox beliefs, he helped create the conditions in which Judaism could adapt and even flourish in the modern world. I am currently finishing a book on Spinoza’s Theological-Political Treatise (1670) and an important section of it addresses his views on toleration.

As democratic majorities push back against liberal policies regarding immigration—witness the recent “Brexit” decision—it is crucial to discuss the role that xenophobia and religious intolerance plays in these debates about national identity. Since the very foundation of American government was created in response to just these kinds of crises, I believe that talking about their historical origins is highly relevant to our contemporary challenges.

Prof. Michael Rosenthal is the new Samuel and Althea Stroum Chair in Jewish Studies as well as professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Washington. He is organizing an international conference on “Spinoza and Modern Jewish Philosophy,” which will take place at the UW in May 2017.

Editor’s note: A shorter version of this article appeared in the “Tolerance Roundtable” section of the Stroum Center’s Jewish Studies Impact Report, Fall 2016. View the entire report here.

Links for further rxploration

- “Was Spinoza a heretic or a theologian?” by Michael Rosenthal (March 2015)

- “The Limits of Tolerance” – Roundtable Introduction by Noam Pianko (Nov. 2016)

- “Jews, Muslims, and the limits of tolerance” by Devin E. Naar (Nov. 2016)

- “The importance of welcoming refugees” by Kathie Friedman (Dec. 2016)

- “Teaching the politics of migration” by Oded Oron (Jan. 2017)