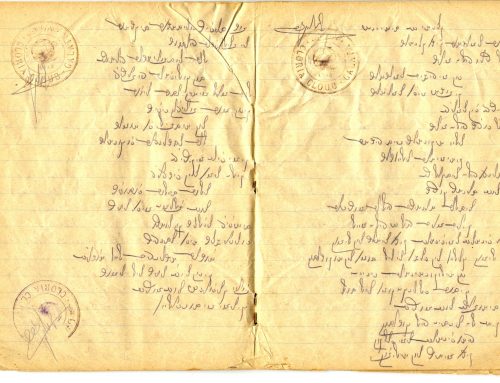

An illustration from a Hebrew primer, “Sefat Yisrael,” published in Canada in 1961. The Hebrew caption reads “Todah Morah” (Thanks Teacher). Image courtesy of Hannah Pressman.

Why don’t more American Jews learn Hebrew?

The answer seems so obvious that the question never gets asked. After all, haven’t we seen the latest Pew survey revealing that soon there won’t be any American Jews left anyway? How much can one expect from a community on life support?

I don’t buy this. The reason American Jews don’t learn Hebrew is because they think they can’t. And I understand why. For much of my life, Hebrew scared me. This became rather inconvenient while I was pursuing graduate studies in Hebrew literature. But I had reasons to be scared.

From childhood I had an intense interest in Hebrew, whose earliest origins were in my mother’s artwork. My mother, a Ph.D. in Jewish studies with a talent for watercolor, created abstract paintings illustrating lines from the Torah and liturgy. She incorporated these verses into her paintings in Torah script—which I, at twelve, learned to read well enough that I became the regular Torah reader for a children’s congregation. Hebrew liturgical phrases became woven through my imagination, often resonating in my daily thoughts. I did not experience this with their English translations, which felt strangely distant to me; my encounter with this “original” Hebrew was so immediate that I later fully appreciated the Hebrew poet Bialik’s comment that reading in translation was like kissing a bride through a veil.

As I got older, I studied Hebrew at every opportunity I could find. These included afternoon Hebrew schools, where I was generally the only student who cared; Jewish summer camps, where Hebrew was largely restricted to public announcements; and later a JCC Ulpan class, where at 15, I was the only student who wasn’t retired. In college I found that my Hebrew was good enough to do what I really wanted to do: slog through Hebrew literature to find authors who lived a modern life while hearing ancient verses in their heads. Fortunately I found them. What I didn’t find was confidence.

You see, I already knew that I could never actually learn Hebrew—real Hebrew, fluent Hebrew, Hebrew where you could understand Israeli TV—simply because only three kinds of American Jews were allowed to learn Hebrew, and I wasn’t any of them.

First, I wasn’t Orthodox. No one was sending me to a gap-year yeshiva; no one I knew threw around Hebrew phrases; no one I knew made aliyah

And then when I was 32, I gave myself a test.

Really Hearing Hebrew

That year I was invited to participate in an international Jewish writers’ conference in Jerusalem. On the first night, the conference hall buzzed with excitement, and also with equipment: everyone’s remarks were being translated simultaneously over headsets into either Hebrew or English. As I entered the hall, I put on an English headset. I needed it, didn’t I? But I quickly found myself distracted by the voice in my ear, and yanked it off. Soon it would be my turn onstage—with another American, two Israelis, and an Israeli moderator who would ask all the questions in Hebrew. I’d wear the headset onstage, I figured. How could I not? What if the moderator or another panelist said something I didn’t understand, and I came up empty in front of 500 people? But as I listened to my fellow writers in the discussions leading up to mine, I thought, lamah lo [why not]?

I went onstage without a headset. During the five-day conference, I was the only American to do so.

It is now very unclear to me why more American Jews do not learn Hebrew. The excuses about assimilation and so forth do not explain why already-committed Jews do not learn Hebrew better, or why we are letting supposed impossibilities stand in our way. And now is exactly the moment when a massive initiative encouraging diaspora Jews to learn Hebrew might actually work. With Israel’s high-tech energy, and with the Israeli government’s eagerness to draw in diaspora Jews, shouldn’t there be an app for that?

As I worked through options for my own children’s Hebrew education, I considered buying the Hebrew version of the commercial language software Rosetta Stone. But why should I have to buy an expensive program which was created without a thought to Jewish culture and which isn’t particularly suitable for children? In a community this creative, shouldn’t there be iPad games and online apps and new learning opportunities that every Jewish kid will want to do, to learn the language they don’t yet know is theirs? Why are there still only three kinds of American Jews who are allowed to learn Hebrew?

At the conference that evening, the canonical Israeli novelist Aharon Appelfeld gave the keynote address. He spoke about learning Hebrew. A native German speaker from Romania, Appelfeld survived the Holocaust as a child and came to Israel in 1946, learning Hebrew as a teenager and consciously choosing it for his fiction. That evening, Appelfeld, who rarely discusses his personal experiences, told us something quite intimate. When he arrived in Israel, he said, he worked on a kibbutz each day and then returned to a small room each night, where he had a notebook and a pen. And there he began to write down the names of each murdered person in his family—not in German, but in the Hebrew he had just begun learning, settling these forgotten people’s names into the ancient letters. And there, he told us, he had them forever, in Hebrew, his.

I listened to him as he spoke, in Hebrew.

Dara Horn is the author of four novels: In the Image (2003), The World to Come (2006), All Other Nights (2009), and A Guide for the Perplexed (2013). She is also the author of a nonfiction ebook, The Rescuer (2011), and co-editor of an academic anthology, Arguing the Modern Jewish Canon (2008). A Harvard Ph.D. in Hebrew and Yiddish literature, she has taught these literatures as a visiting professor at Sarah Lawrence College, City University of New York, and Harvard University, and has lectured at over 200 universities and cultural institutions throughout North America, Australia and Israel. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and four children.

Dara Horn is the author of four novels: In the Image (2003), The World to Come (2006), All Other Nights (2009), and A Guide for the Perplexed (2013). She is also the author of a nonfiction ebook, The Rescuer (2011), and co-editor of an academic anthology, Arguing the Modern Jewish Canon (2008). A Harvard Ph.D. in Hebrew and Yiddish literature, she has taught these literatures as a visiting professor at Sarah Lawrence College, City University of New York, and Harvard University, and has lectured at over 200 universities and cultural institutions throughout North America, Australia and Israel. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and four children.

It is basically a question of willpower. I subscribed to the old “Sh’ar L’Matchil” easy Hebrew newspaper and sat down with a dictionary and broke my head on each article. After 2 months, it got too easy for me and I switched to a regular Israel newspaper. I kept working on it and found after a couple of more months I could understand at least part of the Hebrew-language TV show available in my city. If learning Hebrew is important to you, and you are willing to apply some time and effort to it, it can be done. I am now living in Israel and fluent. I don’t have any special aptitude for languages, so I believe anyone can achieve this.

Ma-ammar man-yen! Todah! Ani lamadatee IVRIT me-az gil shlosheem…lo yadatatee shum meelah lifney zeh. Kvar arbareem shaneem v’ha IVRIT adayeen b’touch Ha Lev!

MARDEVEK

Dara-You ask a very good question but it is an even broader question than you think. You should also ask why most Orthodox Rabbis cannot read, speak or understand Modern Hebrew? You can also ask why the Israeli Government does not do more to facilitate the learning of Modern Hebrew in the Diaspora. More importantly why does the Israeli government not publicize the availability of the scholarly works being produced by the professors at their universities? You must know as I do that there are almost no bookstores or even internet bookstores in the United States that sell academic works produced in Israel written in Modern Hebrew. I know of only one. It is a bookstore in Boro Park but you have to give the owner a secret code and he will allow you to go to the back of the store where he keeps a few titles on hand.

In my area of interest, Tefila, I just learned of two important books that were recently published in Israel. Ma Nishtana by Professor David Henshke and the translation of Leopold Zunz’s treatise on Jewish Liturgy. Luckily I have a source in Israel who keeps me advised of new titles in the field of Tefila. He purchases and sends me the books but these are books that should bring great interest to anyone who leads a Seder or goes to synagogue on a regular basis.

What I am suggesting is that if these books were readily available and publicized in the United States , people who wanted to read them would make the effort to strengthen their knowledge of Hebrew.

My current Hebrew teacher, a native Israeli, has commented on the very poor state of Hebrew-language teaching in the United States compared to South America or Europe. She has taught Hebrew to yeshiva graduates at Yeshiva University and states that even orthodox-educated high school graduates can barely speak Hebrew. I know that my own daughter, after 12 years of Hebrew through high school at non-orthodox day schools, could barely speak Hebrew. I’m not sure the answer to Ms. Horn’s question but Americans are terrible at learning languages, not just Hebrew. I would be hard-pressed to name anyone I know (born in the US to American parents) who speaks a foreign language well enough to buy a rail ticket or order a meal.

I came to Israel with little Hebrew, and started reading. Knowing the basic ways a verb is conjugated, you can go far, with a dictionary in hand. Books are your friends. More than 30 years later, I’m fairly fluent (I work as a translator).

There are two groups of Americans here, one with radically better Hebrew than the other. Jews who grew up in Jewish schools, usually have an enormous leg up. But that’s because everyone else ignores Hebrew, beyond reading the letters enough to fake it through the Hagada. Agree, that some good programs/apps would be a boon. But no less important will be creating the desire to learn, and preferably in children, where the learning comes easier.

[…] speaking of Hebrew in America: Dara Horn has recently wondered why don’t more American Jews learn Hebrew? (via the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies at the University of […]

A great app to learn the Hebrew alphabet for decoding purposes is: Alef Bet Bullseye. https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/alef-bet-bullseye/id1081250079?mt=8

[…] believes that this failure stems from a lack of confidence. Even Horn, who tells us in this recent article that she grew up familiar with Hebrew words and that she was one of those rare, truly engaged […]

There seems to be a very strong association of Hebrew with a language of heritage, and religion. Rather than being treated as a regular foreign language people developed a meaning-heavy an attitude to it. It might be a deliberate rejection, based on the external expectation. A parallel example, being Polish I am “expected” to learn Russian, and this expectation is one of the main factors for my lack of will to do so.

Maybe by removing the pressure, and/or changing the association of Hebrew as a language of the state of Israel (an association which might demand a speaker to have a specific political stance), and a language of prayer, more people will be encouraged to take a stab at it?

you could always try Elef Milim (a 1000 words) a book of “day to day Hebrew”

https://simania.co.il/searchBooks.php?searchType=tabAll&query=%D7%90%D7%9C%D7%A3+%D7%9E%D7%99%D7%9C%D7%99%D7%9D“