Painting [Astronomy] / Louis Duffy, 1953. Source: Creative Commons.

By Shakeah Calluccie

You’ve probably heard of Christopher Columbus (née Cristobal Colon), but have you heard of the Sephardic astronomer who helped him chart his course across the seas?

Abraham Zacuto was a prominent thinker who connected the starry skies to life on Earth and aided in connecting worlds that existed on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

Columbus and his legacy have recently entered a new phase of reconsideration — indeed condemnation and repudiation — for his role in initiating the conquest of the Americas and the displacement and extermination of indigenous peoples across the continents. Statues dedicated to Columbus are literally being toppled across the United States.

How should we understand the role and legacy of Columbus’ Jewish astronomer, himself the victim of persecution, who helped to facilitate not only the connection of the two worlds across the Atlantic but also, however unintentionally, the decimation of one by the other?

Astrolabe of Spanish origin with Hebrew inscriptions. Source: British Museum via Wikimedia Commons.

A Jewish astronomer in the Catholic courts

Abraham ben Samuel Zacuto was born in 1452 in Salamanca, a city in northwest Spain. He would become a well-respected and in-demand astronomer whose work was circulated in Spanish academic circles and in the Portuguese royal court.

At the university of Salamanca, where he would eventually go on to work, Zacuto specialized in astrology and astronomy (at that time synonymous fields). In 1473, at the age of 21, after ensuring that there was no rabbinic prohibition against analyzing the movements of the sun and moon, he began working on what he titled “The Great Composition” (in Hebrew, Ha-hibbur ha-Gadol).

This book of 19 chapters was completed in 1478 and fulfilled Zacuto’s goal of charting the position of the sun, moon, and five visible planets throughout the year. Zacuto created these astronomical tables and the rules for interpreting and interacting with their position in the sky in a way that allowed for ease of reading, similar to that of an almanac.

Zacuto also wrote, in Spanish, “A Brief Treatise on the Influence of Heaven” (Tratado Breve de las Influencias del Cielo), as well as a treatise on solar and lunar eclipses titled De las Eclipses del Sol y de la Luna. In charting the positions of these astronomical entities in an easy-to-read manner, Zacuto allowed navigators to calculate their distance from the equator as well as to set and to maintain their latitude on the open seas.

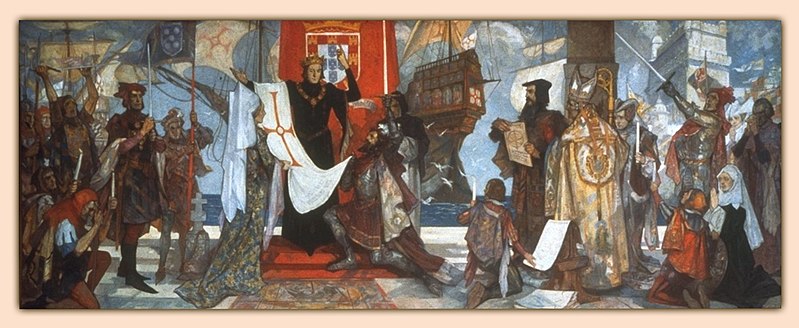

“Vasco da Gama Leaving Portugal,” by John Henry Amshewitz, (1882-1942). In this mural, Abraham ben Samuel Zacuto is shown presenting his astronomical tables to da Gama before his departure from Lisbon in 1497. Source: Archives of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg via Wikimedia Commons.

Knowledge is never gained in a vacuum. Little did Zacuto know that, although his contributions would be used by the Spanish monarchy in advancement of their goals, he would soon be exiled from his homeland, and his treatises would be put to use to colonize the landmasses that came to be known as the Americas.

1492 would mark a turning point for Jews who had lived in Spain for centuries and for indigenous peoples in the Americas. Their fate was not unrelated: A series of papal doctrines issued over five decades would set the groundwork for Christian attitudes towards others, whether in Europe or in the lands they colonized from Africa to India to the Americas.

On March 13, 1492, Isabel I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon ordered that all Jews in Spain either convert to Christianity or be expelled from their kingdoms and territories. Refusing to convert to Christianity, Zacuto moved from his birthplace in Salamanca and was welcomed into the royal court in Lisbon, Portugal. Under King João II, Zacuto became the court astronomer and King Manoel I, the successor to King João II, upheld Zacuto’s appointment.

While in Portugal, Zacuto perfected his model of a copper astrolabe, a tool that measures the altitude of celestial bodies throughout the day and night using the horizon as a beginning point. Those using an astrolabe could identify stars, planets, and the time of day. The devices before Zacuto’s time, however, were impractical to use on the hull of a rocking ship at sea. Zacuto perfected the astrolabe for use on ships, creating what is now known as the mariner astrolabe, which, hand in hand with Ha-hibbur ha-Gadol, enabled far more reliable calculations while navigating at sea.

Zacuto’s works in Columbus’ hands

Columbus famously set sail in 1492, in the same month as the expulsion of Jews from Spain. Before Columbus embarked on his voyage, Zacuto’s student, José Vizinho — a Portuguese Jew — gave Columbus a translation of Zacuto’s work. These astronomical tables, as well as Zacuto’s new astrolabe model, were invaluable to Columbus’ voyage across the Atlantic. In his diary, Columbus states that Zacuto’s work proved useful for sailing across the ocean as well as traversing the land.

Deploying denigrating language and evincing his doctrine of (white) Christian superiority, Columbus wrote that when approached by allegedly “menacing” native people (like in Jamaica), he was able to use Zacuto’s knowledge of an approaching lunar eclipse to threaten the tribe that his God would take the moon away. When the moon was eclipsed, the tribe was said to have retreated due to the imagined superiority of Columbus’s God. Zacuto’s tables with Columbus’ notes, and the diary Columbus kept during his voyage, were found in Columbus’ diary after his death.

What would Zacuto have thought about his calculations being used to uphold the superiority of the Christian God, when keeping his own Jewish faith had led to his exile from Spain?

The same prejudices that uprooted the life of Zacuto and other Jews in Spain and Portugal also shaped the devastation of the indigenous peoples of the American continents. Despite Zacuto having had privileges in the Spanish and Portuguese courts through his work, those privileges were temporary and only afforded him protection for as long as he was seen to be useful to the ambition of the royal courts.

Illustration of Columbus charting his voyage. Source: “Ibn Ezra, Maimónides, Zacuto, sefarad científica : la visión judia de la ciencia en la edad media” by Mariano Gómez Aranda (2003).

Astronomical legacies

On December 5, 1496, King Manoel I of Portugal followed Spain’s lead and signed a decree ordering that Jewish people convert to Christianity or leave. And once again, after publishing invaluable work and being in service to the royal crown in Portugal, Zacuto was sent into exile.

Zacuto left Portugal in 1497 but did not arrive in his next destination – Tunis, Tunisia – until 1504, following a path shared by many other Jews and Muslims exiled from the Iberian Peninsula. Once in Tunisia, Zacuto composed no further major astronomical works, only a few astronomical treatises. His last major work was Sefer Yohasin (“The Book of Genealogies”), where his focus shifted from navigation of the stars to the Jewish luminaries of his own past.

Zacuto’s astronomical tables, however, were re-printed and discussed in Latin, Spanish, Castilian, Arabic, Hebrew, and even in Ladino. In 1568, in the city of Salonica, located all the way on the eastern end of the Mediterranean and then part of the Ottoman Empire, Daniel ben Perahia published a Ladino version of Almanah Perpetuum. Today, Zacuto’s most prominent presence is on the surface of our moon: the moon’s crater Zagut is named after Zacuto.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when Jews were facing expulsions and the era of European exploration and conquest of the Americas began, Abraham Zacuto inhabited a liminal position. His influence reached across different cultures, religions, academic disciplines, and professional fields. His work proved to be influential on major figures within Portuguese, Italian, and Spanish history and, by extension, the history of the American continent.

His scientific influence is not recognized much today, but nevertheless, this Sephardic astronomer’s work made the famous voyages of Columbus possible — and also shows the price of producing knowledge for institutions who are not guided by a sense of our shared humanity.

Stay up-to-date with new digital content from the Sephardic Studies Program. Subscribe to our quarterly e-newsletter.

Shakeah Calluccie is an M.A. candidate at the University of Washington studying International Studies: Comparative Religion. Her graduate work investigates the relationship between late antique astrology/astronomy and religious practices within Jewish and early Christian communities of the Near East and Mediterranean in an attempt to better understand how the widespread, cross-cultural, and cross-religious practice of astrology/astronomy integrated with or separated from the growing and evolving religious practices of Judaism and forms of early Christianity.

Shakeah Calluccie is an M.A. candidate at the University of Washington studying International Studies: Comparative Religion. Her graduate work investigates the relationship between late antique astrology/astronomy and religious practices within Jewish and early Christian communities of the Near East and Mediterranean in an attempt to better understand how the widespread, cross-cultural, and cross-religious practice of astrology/astronomy integrated with or separated from the growing and evolving religious practices of Judaism and forms of early Christianity.

Very interesting article and research, thank you Ms. Callucie! Especially appropriate for me to have read it today, Columbus Day.

Beautiful study, and very well written, rich story telling that keeps us enthusiastically reading until the end.

Thank you.