18th Century map of present-day Northeastern Mexico and South Texas from the Archivo General de Indias.

By Victor Alejandro Castillo

If you’re a Spanish-speaker in South Texas, you’re probably used to being told that you don’t speak “proper” Spanish. Pero asina hablamos — “but we just speak like that.” Strange words like asina — an archaic word meaning “like that” preserved in certain dialects — are evidence of our dual identities along the U.S.-Mexico border; we are told that we are neither from here nor there, and are inept at speaking either language properly.

Yet over the past five years, people have started to embrace this allegedly peculiar form of Spanish; after all, we’re not speaking “improper” Spanish, we’re actually speaking — as they claim — Ladino, the language of Sephardic Jews.

Originally one of many medieval dialects spoken in the Iberian Peninsula, Ladino developed independently from Iberian Spanish after 1492 when hundreds of thousands of Jews were expelled from Spain and Portugal, prompting dispersions to distant locations including present-day Turkey and Greece. The language developed in the diaspora and was the primary language of Sephardic Jews in the eastern Mediterranean world for almost 500 years before finally reaching endangered status in the past few decades.

Needless to say, Ladino didn’t develop in South Texas; we’re actually speaking a dialect of Spanish that preserves many medieval elements in the same way that Ladino does. Yet the claim that people in South Texas “speak Ladino” reveals an emerging trend among Hispanic Americans, and in many other places throughout Latin America, as well: Latinos are beginning to embrace a form of Sephardic identity. (Hispanic is a common term for people of Spanish descent, particularly in the American Southwest; Latino is the author’s preferred term for all people of Latin American descent.)

My interest in Sephardic studies began in 2015 while I was completing my undergraduate degree in history at the University of Texas. That year the Spanish and Portuguese governments approved laws that extended citizenship to descendants of Sephardic Jews as restitution for the fifteenth century expulsions. Among the applicants are a substantial number of Hispanic Americans with ancestry along the U.S.-Mexico border — including me.

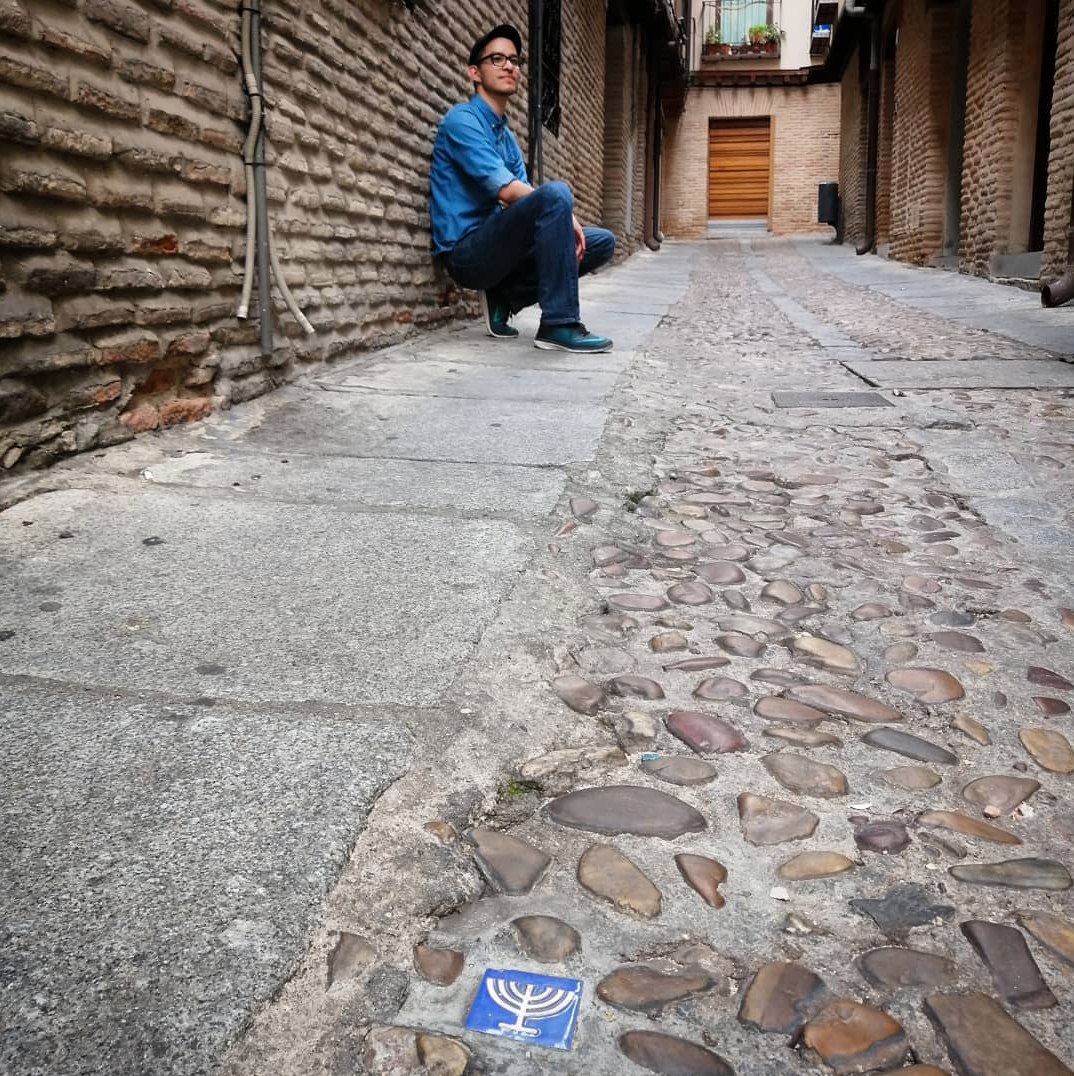

Victor visiting the old Jewish quarter in Toledo, Spain.

The fact that there are descendants of Sephardic Jews in South Texas is largely due to a little-known consequence of history: the 1492 expulsion also prompted mass conversions to Catholicism by Jews who chose to remain in the Iberian Peninsula. For the following century, the conversos, or “the converted” as they became known, were a suspected class and were barred from traveling to the New World out of fear that they would relapse to Judaism.

Still, many managed to slip past the authorities and formed secret communities in remote locations throughout Latin America. In response, the Spanish and Portuguese governments set up Inquisition tribunals all across their colonial holdings in South and Central America that sought to snuff out the clandestine practice of Judaism (and Islam). Many conversos eventually assimilated into their respective communities, thereby wiping out virtually all traces of their Jewish origins; although it is not uncommon to find communities — particularly in the American Southwest — that retained some elements of crypto-Jewish practices, like lighting candles on Friday nights.

For five years now, these populations have been the subject of my research as I’ve helped repatriate dozens of Latinos with Sephardic ancestry to Spain and Portugal. I named my work Sefardí Latino, an ongoing project that focuses on Judeo-converso genealogy, history, and identity. This project has allowed me to witness the emergence of Judeo-converso identity among Latinos firsthand.

Within the Latino community, there is a real yearning for Sefarad, the Hebrew word for the Iberian Peninsula as well as the rich Spanish Jewish culture that developed in the diaspora. This yearning is characterized by the belief that something was taken from us over 500 years ago. The personal nature of learning about our family history and knowing the names of our ancestors who were persecuted by the Inquisition has fueled this phenomenon. And like so many others who have been involved in this process over the past five years, I also believe that many Latinos will have an important role in the preservation and promotion of Sephardic culture.

As interest in Ladino continues to grow — largely in part to preserve this endangered language — I believe there is a sizable community of Latinos who are uniquely positioned to study Ladino while exploring aspects of their own culture and family history. This summer, I am happy to be among the first group of students who will be taking the Ladino Language and Culture class at the University of Washington. For many people in my community, learning Ladino is an act of restitution.

Stay up-to-date with new digital content from the Sephardic Studies Program. Subscribe to our quarterly e-newsletter.

Victor Alejandro Castillo is an MLIS candidate at the University of Washington studying Library and Information Science. His graduate work includes developing a genealogical database that will facilitate Judeo-converso research in order to trace the converso diaspora throughout Latin America. He is a student in the UW’s summer Ladino Language and Culture course with Professor David Bunis.

Victor Alejandro Castillo is an MLIS candidate at the University of Washington studying Library and Information Science. His graduate work includes developing a genealogical database that will facilitate Judeo-converso research in order to trace the converso diaspora throughout Latin America. He is a student in the UW’s summer Ladino Language and Culture course with Professor David Bunis.

Victor, I enjoyed this piece. I was particularly excited to see you are working on your MLIS! My family (the Romeros’) settled in Northern New Mexico/southern Colorado and were one of the families chronicled in Stanley Hordes’ “To the end of the earth”, 2005. My 3rd cousin had our genealogy done while ambassador to Spain during Clinton’s administration. I wish you the best in your studies and career. CAMILA. ALIRE. ALA Past President, 2009/10

Thank you so much! I’ve recently learned we are Sephardic Jew and although my family was in Mexico hundreds of years we actually have a Greek last name and most of us don’t look “Mexican”. I’ve also been fascinated with the Mediterranean area since I was a little girl and decades before I learned this. I almost want to cry as I read your article. Thanks for what your doing!

I was born in San Diego, Texas, and was always told that “Asina”,“muncho” and many other Spanish words were slang.

In the 1990’s I lived in Bulgaria for 4 years. My neighbors were the Ambassador of Israel to Bulgaria and his wife who were originally Bulgarian Sephardic Jews. They told me that Sephardic Jews in Bulgaria still speak Spanish. When we spoke Spanish I was surprised to hear that they used the same South Texas “slang” I remembered! My friends explained that they were speaking the old Spanish spoken since they were expelled from Spain.

Victor, thank you so much for this article – it is so informative and eye opening! My family “Tovah” is Sephardic and am wanting to take a genealogy test to find out more!

My ancestors were from southern France but I suspect (unfortunately) can’t prove or disprove my French ancestors were Sephardic Jew converts. 1 French ancestor had the last name Achim, one was a Paquette, 1 was a Deganais and another was a Fafard. I’ve seen lots of people online living in Portugal with those surnames.

The ways of my Mother were not typical Mexican ways, and some of the words we sometimes used we tried not to because we were told that they were slang.

I have wondered if some of my ancestors were part of the people that changed their name in order to stay in Spain…

Hello. Thank you for writing this article. I’m not from the South West but also share conversó ancestry. I’m from Costa Rica and there was a strong converso community due to the fact that the colony did not receive much attention from Spain. Both of my grandparents ancestry have Sephardic ancestors according to my family tree. It seems that they kept the religion until the late 1700s until they converted and they were part of the first of two Sephardic migration, the second happening in the mid 1800s. From my Pereira side I share ancestry with Sisnando Davides, who was born in Portugal and was known in that place. His father was David Ben Zakkai who was one of the first ones Exilarchs that arrived to Iberia after they started killing this Davidic line in Iraq in the 900s. It was really cool learning about them, their names, and histories. I’m going g to apply for either Spanish or Portuguese citizenship but I’ve heard that Spain has modified this law.

Btw, I grew up hearing “ansina mesmo” by the older folks. I personally don’t use it but I say “eso se descochero (des-koshero)” to say that something turned bad or that it broke. I also say “jupa (huppa)” instead of “cabeza” to imply what goes “on top of you” like a “huppa” (canopy). These are Costarriqueñismos that come from Ladino that we are trying to preserve and the national media are trying to save them by using them on television.

Interesting article.

I’m from San Antonio TX., a Baal Teshuva who lately discovered an “obvious connection” of our Crypto-Jewish ancestors to Tora. Namely, the name of the county in which San Antonio is located. Bexar (county) pronounced in Spanish like the Tora Parashat “Behar” (Leviticus 25:1-26:2). The Name served as a beacon for Bnei Anusim fleeing the inquisition. That is in part why so many Bnei Anusim exist in the Southwestern US today.

I’m happy to see that people are still interested in this topic. We applied for citizenship over two years ago (thank you for your help, Victor!) and are still waiting for approval.

The Society for Crypto Judaic Studies offers an annual conference and will hold a Zoom seminar this November 6, 2022.

Please direct any questions to lagranada.scjs@gmail.com. Free, but registration required.

My book based on family history, Spirits of the Ordinary, as been brought back into print this year, and is available through bookstores or the publisher at https://www.ravenchronicles.org/books

Please consider delivering this article at the 33rd Conference of the Society for Crypto-Judaic Studies in El Paso, Texas this summer, Augsut 13-15.

Go to cryptojews.com for the Call for Papers.

Great work!

My father’ still held Jewish. Beliefs passed down through his grandmother in south Texas. I’ve since found a pocket of surviving crypto Jews who’ve kept a religious continuity. I don’t know how many are left but they have ties to both Nuevo León Mexico, the remote southeastern counties in Texas and San Antonio Texas

I have been searching the origins of my sir name Colon, my great grandfather was born in Paris, France. When I look up location of my sir name Colon, it always takes me to Spain. I was raised catholic. I wonder if a lot of conversos

fled spain for france?