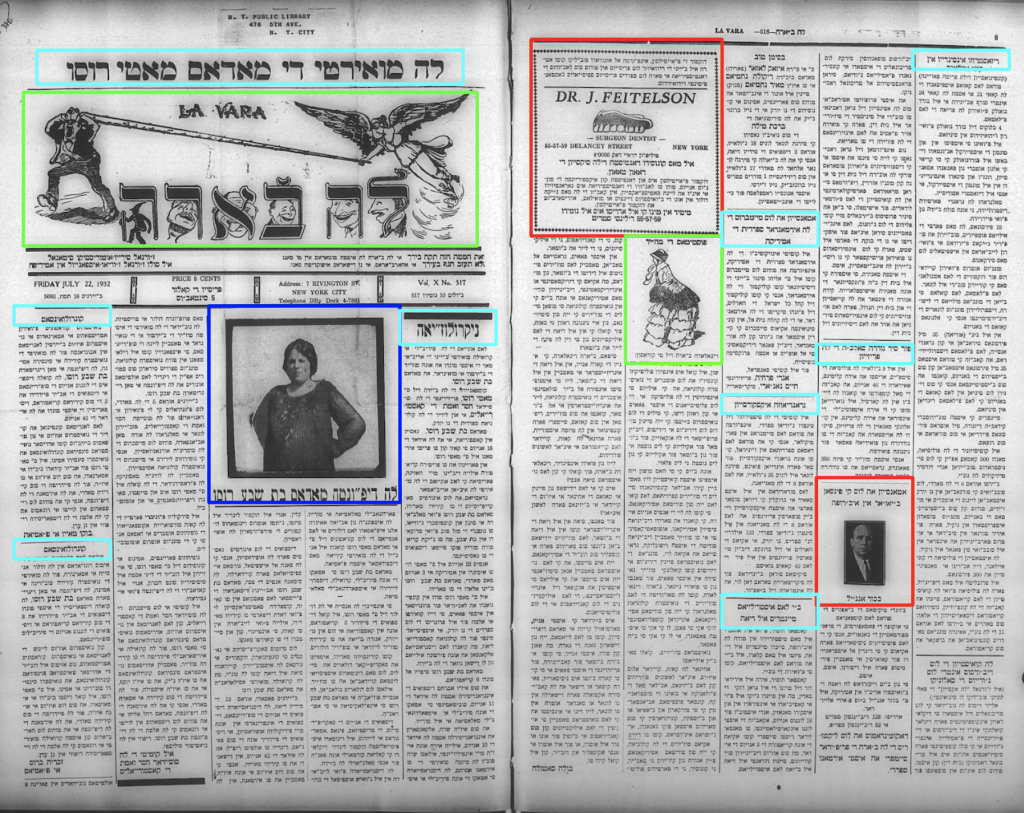

Simulation of a Ladino newspaper — in this case, a 1932 issue of La Vara — in Lee’s Newspaper Navigator tool. (Microfilm copy property of the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection.)

By Hannah S. Pressman

The tech world loves to predict when a wave of innovation is about to crest. For UW doctoral student Ben Lee, the newest blueprint can actually be found in the past: specifically, in the millions of scanned newspaper pages from publications around the country, which are now available digitally with the press of a button.

Lee, a PhD student in computer science, is also a Jewish Studies Graduate Fellow this year.

“Newspapers are the uncharted waters of digital history: there are so many out there and it’s hard to be able to surf through all of them,” Lee, this year’s Richard and Ina Willner Memorial Fellow in Jewish Studies at the Stroum Center, explained during a Zoom interview in October. Through advertisements, photographs, maps, cartoons, and other visual elements, each newspaper can tell a richly textured story about a specific region or city. “You get such a unique slice into daily life that is really hard to capture otherwise.”

To help empower researchers, students, and the public to better search through huge swaths of scanned periodicals, Lee created a powerful search tool called Newspaper Navigator. He fine-tuned the navigator this year as one of the Library of Congress’s two Innovators in Residence. Training machines to perform OCR (optical character recognition) is but one of the many projects Lee is undertaking at the University of Washington’s Paul G. Allen School for Computer Science and Engineering, where he is part of the Artificial Intelligence research group.

Yet as a family genealogist himself, Lee, who grew up in the Baltimore area, is familiar with the other side of the search screen as well. Starting with his grandmother, a native of Boryslav, Poland (now Ukraine) and survivor of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, Lee has spent considerable time tracing his Jewish relatives. He observed, “A lot of the questions that I think about have stemmed from being on the other side of the archive: doing research, visiting collections, and getting a sense of where the limitations are from my own practical experience.” As a result, Lee has a deeply personal investment in improving how the general public can search through the massive collections available at libraries, archives, museums, and other online catalogues.

Learning from both sides of the archive

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington, D.C. was the locus of key turning points in Lee’s personal and professional evolution. He first visited the museum with his grandmother in 2007, and they began doing genealogical research together in the archive there. Then, as a Harvard undergraduate, Lee continued to explore Holocaust studies while majoring in astronomy and astrophysics. His curiosity was especially sparked by a senior-year class on digital history taught by Gabe Pizzorno. After graduation — and exactly ten years after visiting with his grandmother — Lee returned to the USHMM as its first Digital Humanities Associate Fellow.

His primary project was working on the metadata for the millions of identification cards that comprise the International Tracing Service Digital Archive, a database overseen by eleven countries. It was then that his perspective shifted from user to designer: “I had the chance to think about it as a researcher looking at 40 million documents and realizing that there were rich opportunities to apply machine learning or computational tools.”

While laying the groundwork for his graduate studies in computer science, Lee’s time at the USHMM also introduced him to some of the issues inherent to studying Jewish history in general and Holocaust history in particular. Reflecting on his fellowship year, Lee noted, “One thing I’m appreciative of is starting in an archive with materials that are so sensitive and carry as much weight as materials pertaining to the Holocaust do. It’s been formative in thinking about the ethical considerations: when we’re computing, what does it mean to ‘datify’ people? The fellowship left me with a framework and a sensitivity for these kinds of projects.” Now in his third year in the UW’s Allen School, Lee is focusing on the field of exploratory search while maintaining this crucial awareness that behind every identification card or number is a human being with a unique story.

Lee at the Library of Congress during his Innovator in Residence program. (Courtesy Library of Congress Blogs; photo by Shawn Miller/Library of Congress.)

Another fortunate outcome of Lee’s year at the USHMM was a chance meeting with a UW professor who was in town to deliver a lecture on Jewish Salonica. That professor was (you probably guessed correctly) Devin Naar, Chair of the UW Sephardic Studies Program. Thus began “a larger conversation” with Naar about computing, Sephardic history, newspapers, libraries, and digital humanities — a conversation that has been going on for three years and shows no sign of letting up.

“I find it endlessly fascinating to be able to work with historians and learn from people like Devin,” Lee said. “We each bring something different to the table.”

“Ben has brought such enthusiasm and initiative to our collaboration — from our very first conversation (which he initiated),” Naar recalled. “Working for the last several years on digitizing 140,000 pages of Ladino books and documents, we’ve been looking for ways to apply the latest digital technologies to render our source materials as accessible as possible. As a faculty member working in the humanities and social sciences, I felt like we didn’t necessarily have immediate points of convergence with computer scientists or researchers in other related fields. That is clearly changing — and Ben is helping to bridge that divide and bring content and technology together in new and unprecedented ways, especially for Sephardic Studies.”

Searching in Ladino newspapers

When Lee entered the Jewish Studies graduate fellowship this fall, he had the opportunity not only to learn about the field of Jewish studies, but also to tangibly explore ways that his work on search and discovery tools could be applied to the trove of Ladino publications held by the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection. Lee is especially motivated to develop search engines that will recognize printed Ladino as Ladino. Since Ladino was historically written with rashi script, digital scanners often process it as Hebrew, the more commonly recognized Jewish language, rather than understanding it as a language based in Spanish with elements of Turkish, French, Arabic, Hebrew, and other tongues. This type of error points to the need for computer scientists to better train machines to recognize diversity — and not just when it comes to endangered languages like Ladino

What exactly does this mean? We may think that our machines operate from a neutral stance, but unfortunately this is not always the case: bias from the surrounding culture can impact the artificial intelligence tools that we build. If a society tends to marginalize a particular language or group of people, that skewed perspective can be built into the underlying data of the machines that help us search and research. The risk, consequently, is further excluding — or totally erasing — a particular community, its story, or its language.

“There are many documented cases in which machine learning yields biased search results,” Lee explained. “This can lead to racist or sexist notions [from society] being reflected in search results,” as Safiya Umoja Noble, PhD demonstrated in her 2018 book “Algorithms of Oppression.” “It’s become abundantly clear that machine learning not only incorporates some of these biases and real erasing factors, but also perpetuates those biases. Ladino is a perfect example of erasure,” Lee continued. “OCR prioritizes certain languages, for example, English, whereas a language like Ladino has suffered from the fact that it hasn’t been as well studied from an OCR perspective. That, of course, is its own form of erasure.”

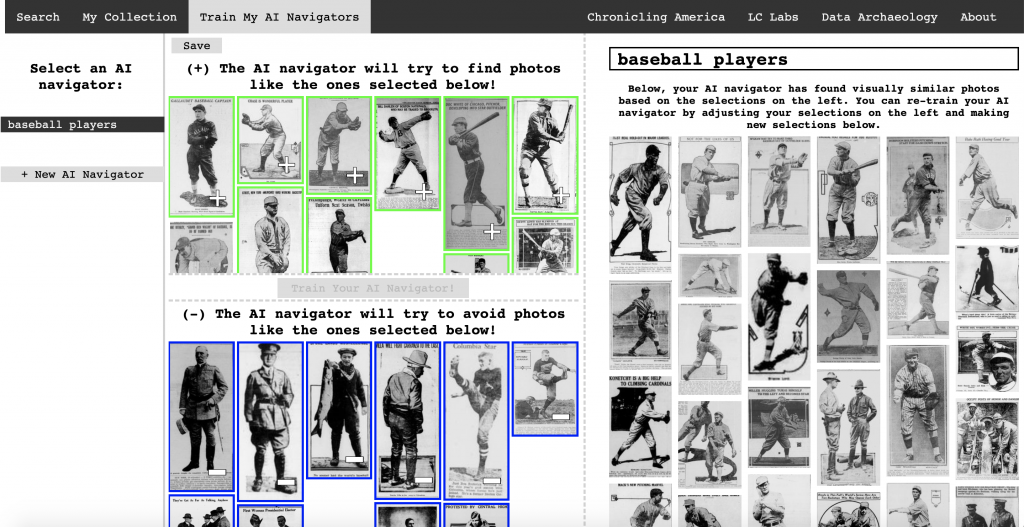

Screenshot of Lee’s Newspaper Navigator tool, which, in this case, is picking out images of baseball players from American newspapers.

Naar agreed: “What’s really exciting about our collaboration with Ben is that we can begin to challenge some of the ‘algorithms of oppression.’ Take the groundbreaking Historical Jewish Press website, which has digitized several hundred Jewish newspapers. The directors of the project [Naar is on the board] had to make a very concerted effort to include a selection of Ladino newspapers among the many titles in Yiddish, Hebrew, and other languages. But now that a handful of Ladino titles are available, the problem is with those algorithms. The OCR technology to date does such a poor job identifying Ladino. This is another place where I hope Ben will come to the rescue!”

One solution Lee advocates is to highlight the rich visual content offered by Ladino newspapers, since “visual print culture speaks to everyone in a way that’s hard to get at through just language.” His Newspaper Navigator tool excels at locating images of all kinds, tailored to specific search criteria. Photographs, advertisements, cartoons, and other elements together comprise a distinct visual language that exists in dialogue with the printed news stories. This powerful lens empowers readers to engage with newspapers like La Vara (published in New York) and El Tiempo (published in Istanbul) regardless of their linguistic skills, granting them access to the regional and transnational Sephardic history captured in these pages.

This kind of empowerment is part of the core mission of the digital humanities, which tries to harness humanities research to better serve communities. Lee’s focus on “how the query process happens” has potential ramifications not just for Sephardic studies, but for any kind of computer-supported inquiry conducted by scholars and the public at large. For that reason, he says, “I’m trying to think about it as an interdisciplinary project that could impact multiple fields.” Encouraged by the Jewish Studies Graduate Fellowship, Lee is collaborating with Naar on a research paper about machine learning, visual content, and the Ladino press. They will co-present at the #DHJewish Conference, a January 2021 gathering of scholars and practitioners examining the state of “the digital turn” in Jewish Studies.

The future of writing history

As someone who knows firsthand the ups and downs of searching for family history, I appreciate Lee’s commitment to bringing others closer to the past through newspapers and other archival materials. Indeed, we are lucky to live in an age where new tools and formats can help ensure that the stories of the past will be retold and will be accessible to anyone who wants to find them in the future. Lee’s work to refine how computers answer questions, particularly his goal to make searches more inclusive and less biased, could be a game changer in the ever-evolving process of generating public history. “Cultural heritage is something collective that we all have ownership over,” he emphasized.

The sheer scale of information encompassed by machine learning is vast, but for this impressive student, the real wonder still lies in what we can find on the micro level: how one newspaper page can open up a whole world. “The coolest stuff for me is, for example, opening up a random page of La Vara from 1930,” Lee said with a smile. “One of the really valuable and incredible things about newspapers is their ability to bring us back into the moment, whether it’s to a place or to a time.” Lee’s passion for exploring the past is one reason why his connection to the Sephardic Studies Program and the Stroum Center will likely last beyond his year as the Willner Memorial Fellow. As a side project, Lee and Naar have been working with Makena Mezistrano, Assistant Director of the Sephardic Studies Program, to develop a crowd-sourcing platform for Ladino materials.

The Ladino expression bushkar kon kandela literally means to search with a candle; it references the small amount of light used during bedikat hametz (checking for leavened bread, an activity often involving young children) before Passover starts. Particularly for the survival of the Ladino language, it is essential to keep searching and shining as bright a light as possible on the near and distant past. The technologies developed by Ben Lee and his Allen School colleagues will potentially provide exactly that kind of illumination for the precious texts and images of Sephardic culture.

As computers and humans continue to forge the writing of history together, it is comforting to know that thoughtful scholars are tackling not just the technical issues, but also the ethical and social issues raised by machine learning. After all, at the end of the day, it’s a real human being who clicks the empty box, types in the word, name, or phrase they’re looking for, and — unsure who or what will appear on the screen — holds their breath and starts the search.

Interested in learning more about the intersection between Ladino and technology? Join us for the 8th Annual Virtual Ladino Day.

To hear Ben speak about his research, watch this recording from a Fall 2020 Stroum Center virtual student coffee hour.

Stay up-to-date with new digital content from the Sephardic Studies Program. Subscribe to our quarterly e-newsletter.

Hannah S. Pressman writes about modern Jewish culture, religion, and identity. She earned her Ph.D. in modern Hebrew literature from New York University and has published her work in a broad range of academic and journalistic venues. Recent publications include contributions to What We Talk About When We Talk About Hebrew (and What It Means to Americans) (University of Washington Press, 2018); The New Jewish Canon: Ideas & Debates, 1980-2015 (Academic Studies Press, 2020); and Sephardic Trajectories: Archives, Objects, and the Ottoman Jewish Past in the United States (University of Chicago Press, forthcoming in 2021). She is currently at work on Galante’s Daughter: A Sephardic Family Journey, a multi-vocal memoir that traces her family’s twentieth century travels from the Levant and Lithuania into southern Africa and beyond. This project was recently recognized with a Research Award from the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute. Dr. Pressman is the former Communications Director, Graduate Fellowship Coordinator, and Hazel D. Cole Fellow at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies.

Hannah S. Pressman writes about modern Jewish culture, religion, and identity. She earned her Ph.D. in modern Hebrew literature from New York University and has published her work in a broad range of academic and journalistic venues. Recent publications include contributions to What We Talk About When We Talk About Hebrew (and What It Means to Americans) (University of Washington Press, 2018); The New Jewish Canon: Ideas & Debates, 1980-2015 (Academic Studies Press, 2020); and Sephardic Trajectories: Archives, Objects, and the Ottoman Jewish Past in the United States (University of Chicago Press, forthcoming in 2021). She is currently at work on Galante’s Daughter: A Sephardic Family Journey, a multi-vocal memoir that traces her family’s twentieth century travels from the Levant and Lithuania into southern Africa and beyond. This project was recently recognized with a Research Award from the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute. Dr. Pressman is the former Communications Director, Graduate Fellowship Coordinator, and Hazel D. Cole Fellow at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies.

Hi, I am Jacob Rosen from Jerusalem. In recent years I published on avotaynuonline.com several surnames indexes of Jewish communities in the Levant including of Alexandria and Cairo. I am told that there was a Ladino publication in Cairo. The Historical Jewish Press website has nothing on it. Do you have any idea where I can find more about it? Thanks

Hi Jacob, I don’t see a Cairo-centric Ladino newspaper in our collection or records, but I do see that the satirical Ladino newspaper El Djugeton (or El Jugueton) was edited by Elia Karmona, who has some works published in Cairo and who seems to have had a printing house (Estamparia Karmona y Zara) located in Cairo — or one that worked with other printers in Cairo. Here is a little bit of info about this newspaper.