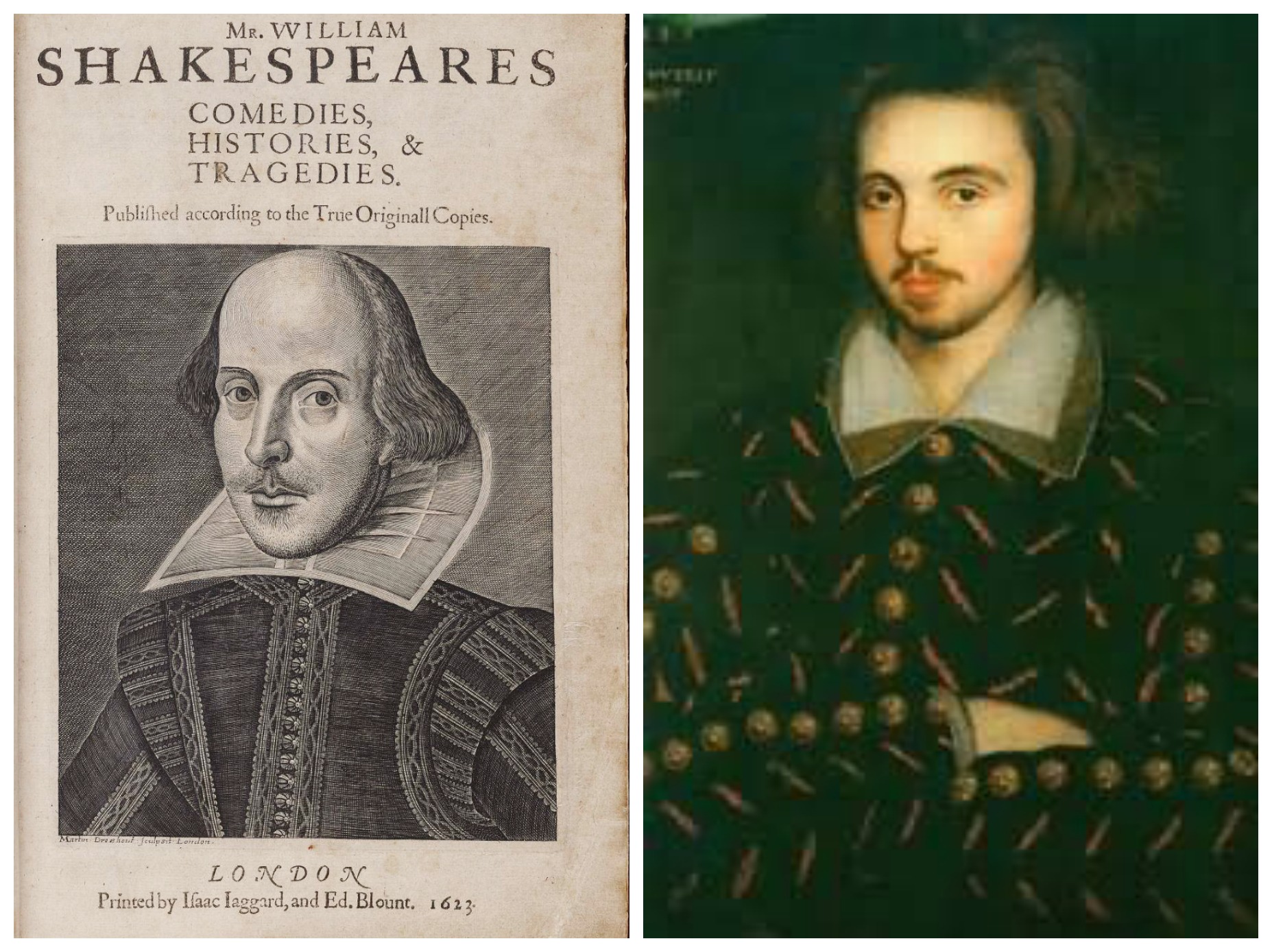

Elizabethan rivals: William Shakespeare (1564-1616) and Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593) are making headlines together.

By Zachary Tavlin

Editor’s Note: On December 8th at 12:00 pm, Zachary Tavlin will be presenting his research on Spinoza’s philosophy and Borges’ literature at our first public research workshop of the year. Prof. Michael Rosenthal will facilitate. Find out more about this new lunchtime event series here!

When Oxford University Press announced that its forthcoming edition of Shakespeare’s complete works will credit Christopher Marlowe as co-author on all three Henry VI plays—the first time a major publishing house has done so—the wheels of the long-running Shakespeare authorship industry recommenced their turning. This new development resulted from digital stylometric analyses or “linguistic computing” based on diction (counting selected words, adjusted for spelling variants) instead of the traditional attention given to collocation or comparisons between ostensibly unique literary styles.

It is not as if, however, there were a shortage of critical theories about the working relationship between Shakespeare and Marlowe before new stylometric techniques confirmed this particular hypothesis. Harold Bloom represents just one node—albeit a hefty one—in widespread influence debates that attempt to isolate turning points in the former’s career where the bard came out from under his rival’s overdetermining shadow to claim an aesthetic and dramatic philosophy of his own.

Yet new discoveries (which we are led to imagine might increase exponentially in the near future) provide opportunities for scholars to re-draw the tired maps of the Elizabethan theatrical world. In the context of the Renaissance “Jewish question,” for instance, the Henry VI plays—around which we can now more properly assume the high volume mixing and mingling of ideas—were written in and around 1591, contemporaneous with Marlowe’s infamous The Jew of Malta.

“The Merchant of Venice, Shylock and Jessica,” by Johann Heinrich Ramberg. Watercolor ca. 1829. Image via Folger Shakespeare Library.

Might recent advances in isolating stylistic contributions to what was clearly a collaborative archive generate new hypotheses about staged anti-Semitism in the Elizabethan period? A few of the longstanding questions about Marlowe and Shakespeare is whether the Shylock of the latter’s The Merchant of Venice (likely written between 1596 and 1598 but not published in quarto until 1600, nevertheless clearly of an ascendant period in Shakespeare’s growing originality, contemporaneous with the Henry IV plays and shortly preceding the high tragedies) was a Jewish type or antitype, a primarily serious or comic figure, a sincere portrait of a societal class or an ironic revision of a popular revenge genre character.

The hope is that every quasi-definitive node in the history of professional meetings between these two enormous dramatic minds—even for those of us who find every naïvely renewed query upon the bard’s status as either an anti- or philo-Semite to be tedious, as if the answer could ever be decisively determined—will add real grist for the specialist mill and provide, if not any clear answers about Shakespeare’s ethnic politics (the dearth of personal correspondence left to posterity seems to put such dreams beyond our ken forever), more precise questions to ask.

I will advance one conjecture here, safely enough away from the fiery furnace of peer review, as a mere example of what such a momentous editorial decision might suggest. Consider one of Malta’s most outrageous passages, Barabas’s conflation of his love for his daughter with his love for gold, followed by a similar passage from Merchant:

O my girl,

My gold, my fortune, my felicity,

Strength to my soul, death to mine enemy;

Welcome, the first beginner of my bliss!

O Abigail, Abigail, that I had thee here too,

Then my desires were fully satisfied.

But I will practise thy enlargement thence:

O girl! O gold! O beauty! O my bliss! Hugs his bags. (Marlowe, The Jew of Malta, II, i, 47-54)

My daughter! O my ducats! O my daughter!

Fled with a Christian! O my Christian ducats!

Justice! The law! My ducats and my daughter! (Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice, II, viii, 15-17)

The speaker in the second quote is not Shylock, as one might assume, but the character Solanio poking fun at the Jew. It has been noted extensively by critics that a local period audience would have recognized in-jokes like this while at least acknowledging the levels of complexity contained in such elusive allusions.

But while the former passage, as I’ve mentioned, was written during a time we now accept as one of professional comradeship on the part of the playwrights, the latter was composed after the grisly death of Marlowe. What would change for us if we re-considered a joke at the Jew’s and Marlowe’s expense as a posthumous tribute to a time when the great rivals were productive in collaboration? What sort of figure does that make the Jew? And for what sort of reader might this matter?

Zachary Tavlin is the 2016-17 Richard M. Willner Memorial Scholar at the Stroum Center. He is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at the University of Washington. He received his BA in Philosophy from The George Washington University in 2011, and his MA in Philosophy from Louisiana State University in 2013. He is currently writing a dissertation on nineteenth-century American literature, the visual arts, and embodied phenomenology. He has published numerous articles and book chapters on topics including psychoanalysis, Victorian materialisms, eco-criticism, poetics, philosophy and American literature, and film theory. Zachary’s project for the Jewish Studies Graduate Fellowship is entitled “Jewish Philosophical Collectives through the Gate of Heaven: Herrera, Spinoza, and Borges.”

Zachary Tavlin is the 2016-17 Richard M. Willner Memorial Scholar at the Stroum Center. He is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at the University of Washington. He received his BA in Philosophy from The George Washington University in 2011, and his MA in Philosophy from Louisiana State University in 2013. He is currently writing a dissertation on nineteenth-century American literature, the visual arts, and embodied phenomenology. He has published numerous articles and book chapters on topics including psychoanalysis, Victorian materialisms, eco-criticism, poetics, philosophy and American literature, and film theory. Zachary’s project for the Jewish Studies Graduate Fellowship is entitled “Jewish Philosophical Collectives through the Gate of Heaven: Herrera, Spinoza, and Borges.”

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)

Leave A Comment