The opulent decorations in the living room, Musee Nissim de Camondo, Paris.

By Christina Sztajnkrycer (Sutton)

While in Paris for a month following fall quarter, I had the chance to return to one of my favorite museums, the Musée Nissim de Camondo. It is situated on the border of the 8th and 17th districts in a western section of the city, in one of the more elegant neighborhoods. Considering the panoply of museums found in diverse and intriguing locations throughout Paris, choosing which to visit and then forming a preference based on the collections, setting, and overall experience can be tricky. The Musée Nissim de Camondo, however, easily stands out from the crowd due to the unique history of the Camondo family, the neighborhood surrounding the museum, the museum’s architecture, and the collections it contains.

Moise de Camondo (1860-1935) came from a Sephardic family that ran one of the most successful banks in the Ottoman Empire. He continued the banking business in France.

I first became aware of the Camondo family in reading Edmund de Waal’s The Hare with Amber Eyes. While the story of the amber-eyed hare is a historical work following the trajectory of a Russian Jewish family, the Ephrussi of Odessa, there are many parallels with the Sephardic Camondo family of Venice and Istanbul. Both the Ephrussi and the Camondo families, similar to the Rothschilds, came to inhabit some key European banking capitals undergoing great industrial growth throughout the nineteenth century. Both arriving in Paris early in the 1870s, the two families chose the same and very specific neighborhood in Paris in which to establish their households and businesses. The elected neighborhood is often referred to as la plaine Monceau, loosely translated as the hilly field, with a whimsical park of similar appellation, le parc Monceau, at its center. Living on the rue de Monceau, a street where “Jewish money was a key denominator,” members of the Ephrussi and Camondo families found themselves at home amidst the Jewish aristocracy of nineteenth-century Paris.[1]

At the end of The Hare With Amber Eyes I was left with the impression that I had just barely scratched the surface of a much more complex history of a unique Jewish presence in the plaine Monceau. I wanted to know more about the composition of this supposed Jewish aristocracy that had become such an essential element of this particular Parisian neighborhood. My curiosity led me to another historical work, Le dernier des Camondo, or The Last of the Camondo Family, by Pierre Assouline, a French journalist of Moroccan Jewish origins.[2] It was in this thoroughly researched and intelligently written history of the Camondo family, with particular focus on Moïse de Camondo, that I discovered the existence of the Musée Nissim de Camondo at 63 rue de Monceau and began to uncover the unique and curiously Jewish influence in the luxurious upper-class neighborhood that is la plaine Monceau.

While reading Le dernier des Camondo and researching farther back into the history of the plaine Monceau, I discovered what Edmund de Waal had hinted to as the “Jewish money” behind the origins of the neighborhood. The plaine Monceau is in fact a more recent part of Paris, annexed to the city in 1860 with other peripheral neighborhoods such as Belleville, Montmartre and Charonne. Before annexation, Emile and Isaac Pereire, having “made their fortunes as financiers, railroad-builders and property magnates, creating colossal developments of hotels and department stores,” purchased the plaine Monceau with the park in the center and started to develop the surrounding area.[3] Theses two Sephardic brothers from Bordeaux, also creators of the fancy neighborhood surrounding the Opéra Garnier and the Hôtel de la Paix in Paris, dreamed a luxurious future for this soon-to-be elitist neighborhood. The homes on the rue de Monceau span several street numbers, “for ninety-five numbers, there are only ten” hôtels particuliers, or private mansions.[4] But the Pereire brothers were not just savvy investors with a taste for luxury, they also knew how to attract and convince the wealthiest Jews of France, Europe and the Mediterranean basin to come live in the plaine Monceau along with many other members of the Parisian high society. The outcome of the Pereires’ vision was “an unprecedented mixture of nobility of the Ancien Régime and Empire, Jewish aristocracy, high society Protestants, members of the rich industrial and financial bourgeoisie.”[5]

Musée Nissim de Camondo at 63 rue de Monceau, Paris.

When the Camondo family arrived in Paris, from Istanbul by way of Venice, they came into possession of three homes in the plaine Monceau, “at number 61, is the house of Abraham de Camondo, with his brother Nissim at 63 and their sister Rebecca over the street at number 60.”[6] It was Moïse’s father, Nissim de Camondo, who purchased the property at 63 rue de Monceau from a certain Monsieur Violet, a wealthy entrepreneur of the industrial bourgeoisie. Before the Camondo family purchased the Violet home, it had already become famous in Emile Zola’s 1872 novel, La Curée, as the residence of the fictional Aristide Rougon, better known as Saccard, an adept of the Paris stock exchange and reckless speculator who could not have enough gold in his luxurious mansion on the edge of the parc Monceau. Novels like Zola’s La Curée generated a sort of mythical aura of unimaginable wealth surrounding the plaine Monceau that came to be seen as the most stylish neighborhood of the Belle Époque for both foreign and French aristocrats alike.

Despite the celebrity status of the address, Moïse de Camondo decided to have the home razed in 1910 following inheritance from his late mother, Élise Fernandez de Camondo. Working with René Sergent, a neo-classical architect and fervent admirer of all things Ancien Régime, Moïse designed a faithful interpretation of Louis fifteenth’s Petit Trianon palace of Versailles, designed by Ange-Jacques Gabriel and completed in 1769. The use of a royal palace as inspiration for Moïse de Camondo’s family home might seem unusual and potentially very ostentatious for a Jewish residence in a twentieth-century Parisian (albeit elitist) neighborhood. However, this devotion to the most decadent era of France’s aristocracy and the last few kings to reign before the Revolution of 1789 was typical amongst the wealthy classes for the times. The eighteenth century had in fact become very fashionable by the middle of the nineteenth century and there was what one might call a sort of eighteenth-century mania. This passion for the eighteenth-century style can be traced back to the noble art and antiques collector, the baron Léopold Double, who was among the first few collectors to begin seeking out and acquiring eighteenth-century paintings, tapestries, furniture, sculptures and elegant porcelain and silver dinner services as early as the 1840s.[7] The Goncourt brothers, as permanent figures of the Parisian high society social scene who published all their thoughts, impressions, critiques, and gossip concerning their social life and the acquaintances encountered, were essential figures in spreading frenzy for the eighteenth-century style as “the natural décor of the high society”.[8]

The Petit Trianon palace of Versailles, built by Louis XV and completed in 1769, served as the inspiration for Moise de Camondo when he built his Parisian mansion.

For such foreign Jewish aristocrats as Moïse de Camondo, an attachment to the Ancien Régime was also a way of demonstrating an ultimate assimilation and appreciation of French culture. Moïse de Camondo, along with many other affluent Jewish figures of nineteenth and early twentieth-century Paris, caught the eighteenth-century fever, “la passion des collectionneurs.” He slowly began collecting eighteenth-century pieces and, by the time he came into the inheritance of the family home at 63 rue de Monceau, Moïse had accumulated such an immense collection that recreating the ideal setting in which to house all of his eighteenth-century masterpieces was a logical next step. Furthermore, since the Petit Trianon is considered an archetype of eighteenth-century neo-classical French architecture in which analogous masterpieces of art and furniture were found, an authentic interpretation was the only worthy venue for Moïse’s collection. During the three years of construction, Moïse continued to frequent the most exclusive antique dealers, haunting auction halls and estate sales, tirelessly seeking out the most unique pieces of furniture, often recuperated from aristocratic castles and royal domains destined for demolition. When Moïse’s personal Petit Trianon was finally complete in 1914, the ensemble of works by almost all of France’s eighteenth-century master craftsmen gave the impression that Moïse had in fact raided the Royal Furniture Repository of Versailles.[9] The resulting palace in the plaine Monceau, perfectly furnished and decorated with original eighteenth-century pieces, was stunning but not without some significant social implications.

Although the zeal for eighteenth-century taste and style seems to have been universal throughout Paris’ high society, there were some who disagreed with the sale of works of art and furniture once belonging to aristocratic and royal families to those with such foreign, diverse, and Jewish origins. Despite Moïse’s sincere passion for eighteenth-century French style, the accumulation of objects previously found in the castles of the ancient nobility was not well perceived by the majority of what was left of the French aristocracy and vast working class often of once very catholic and peasant origins. Similar to the wealth of the Rothschild family, the financial ability to acquire works of craftsmanship such as the roll-top desk by Jean-François Oeben, the same cabinetmaker who created an almost identical roll-top desk for Louis the fifteenth at the Versailles castle, only fueled anti-Semitic sentiments among many French who had the mistaken impression that their country was being overrun by wealthy and internationally connected Jews.

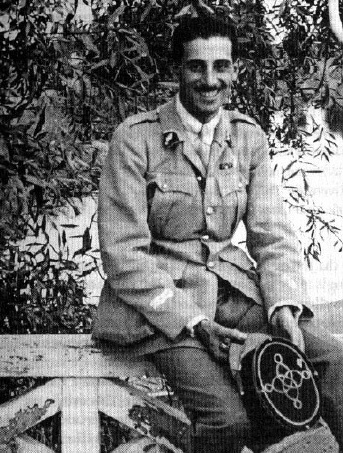

Lieutenant Nissim de Camondo (1892-1917) was supposed to enter the family business in France, but died in an air battle in 1917. The museum was created in his honor.

When Moïse passed away in 1935, he left the Camondo home at 63 rue de Monceau with the entire collection inside to the French State. His only stipulation was that it be maintained untouched as an artistic dwelling of pure eighteenth-century style. Moïse chose the name in homage to his father and son, both named Nissim de Camondo, the latter having died in 1917 as a pilot in the French army. Surviving Nazi occupation from 1940 to 1944, the museum bordering the parc Monceau remains today miraculously intact. Walking through the lavishly decorated and furnished rooms of the Camondo home, one has the impression of being transported in time and space to the noble era of Louis the fifteenth, immersed in the delicate, refined, and intelligent “art of living” that so characterized the golden century of French Enlightenment.

Creating a setting nearly identical to that of the Petit Trianon and furnishing it with masterfully crafted eighteenth-century furniture was Moïse de Camondo’s way of showing more than just allegiance and gratitude to France and the Enlightenment ideals that lead to liberty and prosperity for countless Jewish families following the revolutionary Jewish emancipation of 1791. Fully immersing himself in the eighteenth-century ambiance was his manner of becoming more French than the French, more noble than the modern aristocrats.

At the conclusion of Le dernier des Camondo, the significance of the title, The last of the Camondo family, becomes clear. The Musée Nissim de Camondo is one of the few tangible pieces of evidence of the Camondo family’s existence in Paris. Their long and meandering journey departing from Spain during the Inquisition culminated in Nazi-occupied Paris. The Camondo family line ended tragically when Moïse’s daughter, Béatrice, and her two children, Fanny and Bertrand, were deported to Auschwitz in 1943. Not one Camondo returned. For many who visit this peculiar museum, the unique Jewish identity of its creator remains unknown, hidden beneath the opulence of the eighteenth-century French style. In the whole house there are only a few items indicating Moïse de Camondo’s Jewishness. There are two pairs of separated sinks in the vast kitchens and there are two beautifully bound books of Hebrew prayers and rituals for Rosh Hachana, Yom Kippur and Pesach, the 1867 edition by the Parisian rabbi Élie-Aristide Astruc, stamped with the initials “M. de C.” in gold and crowned with flowers and pearls.

I view the Comandos’ story through the lens of nineteenth-century French literature; my research focuses on Paris and the way in which French authors integrate Jewish characters into their fictional representations of Parisian society. For me, the true story of the Camondo family seems to confirm a Jewish predilection for France, the Enlightenment, and the Revolution. Within the novels of many writers of nineteenth-century France, from Honoré de Balzac in the first half of the century all the way to Marcel Proust and the early years of the twentieth, Jewish characters fill the roles of antique dealers, art collectors, bankers, journalists, politicians and more. What is common to all these Jewish figures is their ability to thrive within French culture and traditions, sometimes forsaking Jewish principals, sometimes maintaining deep connections to the Jewish faith and sustaining memories of Jewish history.

An archway with an architectural flourish reveals the name of the museum, named in memory of Moise De Camondo’s father as well as his son.

After visiting the luxurious Camondo family home, one might think that Moïse de Camondo had made his best attempt to trade his Jewish origins for those of an Ancien Régime aristocrat, but the history of the home, the park, and the surrounding neighborhood tells another, much more complex story of post-revolutionary French Judaism and the Jewish men who became the Jewish princes of French culture. The Musée Nissim de Camondo is not just a lingering trace of the Camondo family and their tragic destiny; it is the magnificent confirmation of the great contributions that the Jewish community of Paris offered to France throughout and beyond the nineteenth century.

Notes:

[1] Edmund de Waal, The Hare with Amber Eyes, New York: Picador, 2010, p. 27.

[2] Pierre Assouline, Le dernier des Camondo, Paris: Gallimard, 1997.

[3] Edmund de Waal, p. 27.

[4] Pierre Assouline, p. 23.

[5] Ibid. p. 23.

[6] Edmund de Waal, p. 28.

[7] P. L. Jacob Bibliophile, Catalogue des objets d’art, tableaux anciens, livres composant la collection Doubledont la vente aura lieu les lundi 30, mardi 31 et mercredi 1er juin 1881, Paris : Pillet et Dumoulin, 1881. (View here.)

[8] Pierre Assouline, p. 28.

[9] Ibid. p. 49.

Christina Sztajnkrycer (Sutton) is the 2014-15 Richard M. Willner Memorial Scholar at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. She is a third-year PhD student in the Department of French and Italian Studies, having earned her MA from the University of Washington in 2011. In her studies, she became interested in the recurrence of Jewish characters in 19th-century French fiction centered on the rapidly evolving Parisian society. Fascinated by the intrinsically linked histories of France and French Jews of the 19th century, Christina is now working on the representation of Jewish identity in French and Francophone fiction of the larger 19th century. The literature Christina is studying spans from the 1789 French Revolution all the way to the arrival of the North African French-speaking diaspora in France in the 1950s.

Christina Sztajnkrycer (Sutton) is the 2014-15 Richard M. Willner Memorial Scholar at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. She is a third-year PhD student in the Department of French and Italian Studies, having earned her MA from the University of Washington in 2011. In her studies, she became interested in the recurrence of Jewish characters in 19th-century French fiction centered on the rapidly evolving Parisian society. Fascinated by the intrinsically linked histories of France and French Jews of the 19th century, Christina is now working on the representation of Jewish identity in French and Francophone fiction of the larger 19th century. The literature Christina is studying spans from the 1789 French Revolution all the way to the arrival of the North African French-speaking diaspora in France in the 1950s.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)

Thanks! I’ve been interested in the transformation of Paris during the 19th C but have not previously seen it from a Sephardic perspective. Plus you have to wonder at how the museum managed to escape requisitioning and looting by the Nazis in WWII. A sad story that recalls of “The Garden of the Finzi-Continis”.

Good luck in your work going forward!

Philip Ferrato

Most interestingly, I lived at 7rue Vezelay chez d’Aubared in 1974. My boyfriend Pierre went to the Camondo school studying industrial design with the son of Charles Jordan. We used to meet at the corner cafe! Many years later I went back to visit & saw it was a museum! It was FABULOUS! Always just thought it was a school!

While the author alludes to it, the Camondo family contributed immensely to the culture and life of France, including a massive donation of priceless impressionist and Japanese print art to the Louvre, including works by Cezanne, Delacroix, Manet and others. They helped finance the Paris Metro’s initial construction and funded numerous artists and artistic endeavors. There is much we can learn from their lives and times. I am writing a book (historical fiction) about the family and would welcome any input.

Totally fascinating , read the de Waal book a while ago but had no inkling of the whole Monceau area and story.

Thank you much

Camondo family greatly contributed to istanbul and Turkey beginning oend of 19th century. Thanks

Being originally from Istanbul, as being Greek from mother, and as being Turk father, going to French School in Istanbul, being in Paris several times, knowing Monceau Rue, and has been living in the USA, 50 years, but unfortunately not knowing Camondo family and learning all these informations in this article gave me tremendous plaisir. This article today gave me the feelings more clearly who I am and how I have been influenced by all those cultures. Thank you so much, so interesting.

.

We’re so glad to hear that. Thanks for reading!

S. Bolger. Dublin. Ireland

Very interesting. Who is the publisher of The last of the Camondo? I would like to read it.

My mother lived with Beatrice and her family while studying dressage. She was Frances leading Equestrian at the time. When the war started she tried to get them to come to England with her but they decided to stay. The French interned them and later deported them to Auschwitz. The daughter died of typhoid on arrival her father and brother were gassed 3 months later. Beatrice never got to the camp at some point she was sent to the Polish salt mines where she was shot by the guards before they could be liberated by the Russians. It took a while for my mother to finally find out their fate. Because she had been living in Paris and her younger sister worked in the Forien Office she to joined the British SIS & was transferred to the SOE. I have a picture of Beatrice my Mother always kept. On the back is a letter from a French cousin of Beatrice’s family telling my mother of the family’s fate. My mother thought of them as a second family. Her background was Scottish Presbyterian and her grandfather a leading Glasgow banker her mother’s family owned the Stag Line shipping company (the first to build an iron steamer on the Tyne!