Left: Detail from the Knesset Menorah in Jerusalem, showing Hillel the Elder explaining Torah to a man on one foot. Photo by Deror Avi. Right: Cover from a translation of “Pirkei Avot” (“Sayings of the Fathers”).

By Naomi B. Sokoloff

Imagine the Hokey Pokey as penned by William Shakespeare. Here’s the opening to a version of just such an imagined text, which was the winning entry in a writing contest sponsored by the Washington Post in 2003:

O proud left foot, that ventures quick within

Then soon upon a backward journey lithe.

Anon, once more the gesture, then begin:

The ending appears this way:

The Hoke, the poke — banish now thy doubt

Verily, I say, ’tis what it’s all about.

Now consider: How would the Hokey Pokey sound if written by Rabbi Hillel two thousand years ago? The answer is easy — at least, it’s easy to identify the last line of the refrain: “zot hatorah kulah.” This rousing chorus, sung by children in Israel and at American Hebrew schools, is, in its own way, a winning adaptation of the original line, “that’s what it’s all about.”

Appealingly pithy, singable, exuberant, the words come from Talmud (Shabbat, 31a), where Hillel explains the golden rule to a potential convert who is standing on one foot. Challenged to teach Judaism in a way that is both brief and comprehensive, the sage pronounces the foundational moral principle, “That which is hateful to you, do not do to others,” for, “that is the whole Torah.”

The English line from the Hokey Pokey did not have to be translated that way. Instead of zot hatorah kulah, the Hebrew lyrics could have been “zeh kol ha‘inyan” – but this phrase sounds more like “here’s the thing,” or “that’s what it’s about,” or perhaps “that’s all it is.” None of these alternatives fully captures the phrase “that’s what it’s all about.”

In contrast, zot hatorah kulah is at once a concise, apt, and inexact reference that calls to mind a very long tradition. Bilinguals will grasp the connotations instantaneously, and smile. The discrepancy between the image of Rabbi Hillel expounding Torah and the image of kindergarteners dancing to a simple, hokey tune makes for comic discordance.

Photo by Robert Couse-Baker.

Amusing? Yes. But not only that. It can spur us to think about the distinctive versatility and power of modern spoken Hebrew: Even in its everyday, most ordinary routines and in the setting of popular culture, this language can spark a cluster of associations. It negotiates constantly between past and present, religious and secular spheres of meaning, Jewish culture and outside influences. It is constantly evolving, and when it comes into contact with innovative ideas and with other cultures, Hebrew absorbs novelty by coining words, by transliterating foreign expressions, by wrestling with translation, or –- as here -– by drawing on its own vast reservoir of traditional sayings.

Is the use of sacred language in a secular ditty offensive? Not to my thinking. The reference to Talmud injects into the song an entertaining, jokingly philosophical dimension (not unlike the slogan often emblazoned on T-shirts, “What if the Hokey Pokey is what it’s all about?”).

More importantly, rather than trivializing a Talmudic saying, the Hebrew Hokey Pokey serves as a reminder about the richness of the word “Torah,” which has many meanings. It can refer to the five books of Moses, or the Bible more generally, or, even more broadly, to Jewish learning as a whole, and it can also refer in Modern Hebrew to other kinds of instruction, as in “torat hasifrut,” the field of literary theory or the academic study of comparative literature. As the Hokey Pokey shows, Modern Hebrew can bring alive the past, and knowing both English and Hebrew can generate awareness of and insight into language.

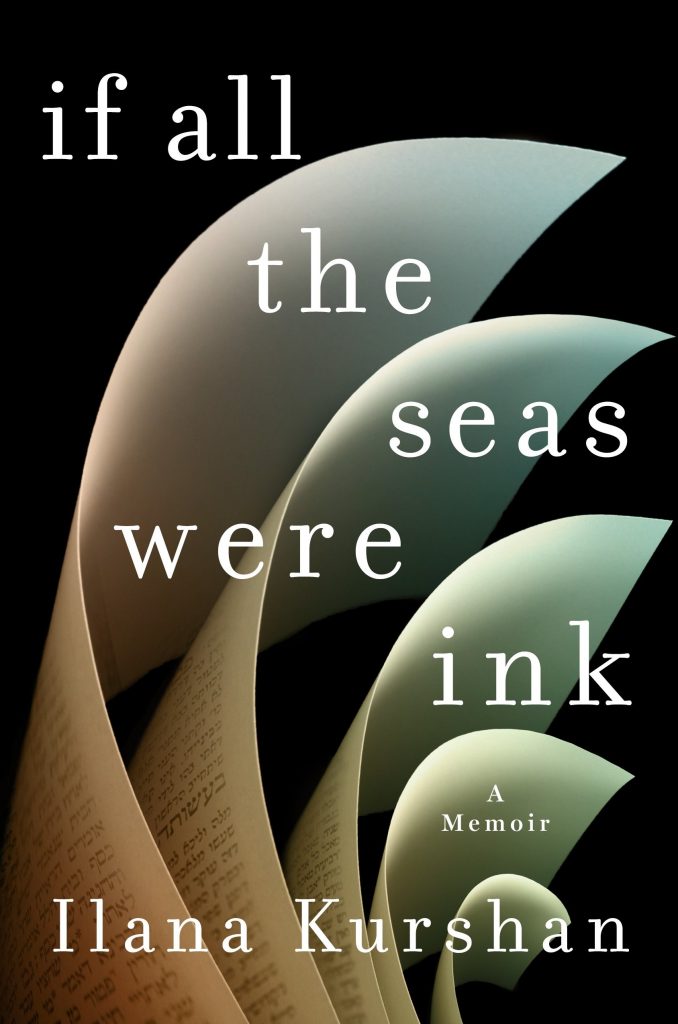

An example comes from a book I recommend highly: Ilana Kurshan’s memoir, “If All the Seas Were Ink.” Kurshan is an American who moved to Jerusalem. After a few years people asked her, are you staying for good? Their question, in English, was intended of course to inquire if Jerusalem had become her permanent home. But, as a speaker of both English and Hebrew, Kurshan heard the question not only that way but also as a translation of the expression “letovah” – meaning, for the sake of goodness or, as in the rabbinic saying “gamzu letovah,” is it for the best?

An example comes from a book I recommend highly: Ilana Kurshan’s memoir, “If All the Seas Were Ink.” Kurshan is an American who moved to Jerusalem. After a few years people asked her, are you staying for good? Their question, in English, was intended of course to inquire if Jerusalem had become her permanent home. But, as a speaker of both English and Hebrew, Kurshan heard the question not only that way but also as a translation of the expression “letovah” – meaning, for the sake of goodness or, as in the rabbinic saying “gamzu letovah,” is it for the best?

And she deliberated on all those meanings. Bilingual understanding not only sharpened her wit: It made her more thoughtful; it brought the wisdom of the past into the present; it enriched it inner life; and it built bridges between her American background and her Israeli experience.

Talmud is often referred to as a sea. That metaphor may apply also to the Hebrew language as a whole. There are many points to wade or to dive in to its great literary tradition, and endless possibilities once inside for exploring new depths. Dip your foot into the sea of Hebrew and, in any direction, discover more. Or, might we say, put your left foot in, put your left foot out, put your left foot in and shake it all about. Even standing on one leg or doing something as easy as the Hokey Pokey, Americans can benefit a great deal from learning Hebrew and learning about Hebrew.

In “Pirkei avot,” “The Sayings of the Fathers,” Rabbi Ben Bag Bag notes the capaciousness of Torah and exhorts: “Turn it and turn it again, for all is in it.” The Hokey pokey urges: “Turn yourself around.” Wherever you start with Hebrew — with the twirls of a children’s dance or the rigorous demands of Talmud study, the language will lead you in ever new directions.

And here’s where I prefer the Hebrew Hokey Pokey over the “Shakespearean” version. The latter insists on authoritative knowledge (“Verily, I say, ’tis what it’s all about”), but the Hebrew version, with its Talmudic echoes, emphasizes that there is always more to learn. After all, Rabbi Hillel starts with the basics, the golden rule, and notes, “Zo hi kol hatorah kulah,” “This is the whole Torah,” but he also adds: “The rest is commentary, go and learn.” That’s what it’s all about.

Naomi Sokoloff‘s new book, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Hebrew (and What It Means to Americans),” co-edited with Nancy Berg, presents ten essays on the past, present, and future of the Hebrew language in the United States and globally. It is available now from the University of Washington Press; read a recent review and interview with Naomi Sokoloff. Read more short essays on Hebrew by the contributors here.

Further reading

- Wonder Woman and the superpower of Hebrew by Naomi Sokoloff (2018)

- “This one facing the other”: Learning Hebrew through translation by Adriana X. Jacobs (2018)

- Other essays on Modern Hebrew

Leave A Comment