Canadian National rail service connecting Toronto with Sarnia and other cities in Ontario. 1970. Via Wikimedia Commons.

By Wendy Zierler

In the summer of 1970, my parents did the unthinkable, at least according to the logic of their own little world.

For all of my father’s forty-two years and for the full eighteen years of my parents’ marriage, they had lived in Sarnia, Ontario, a small petroleum city on the Ontario-Michigan border. My father’s parents had emigrated from Galicia to Sarnia in the 1920s and had established a successful retail furniture business in downtown Sarnia, which my father joined after high school.

In Sarnia my family lived a comfortable, pleasant, slow-paced life, with friendly gentile neighbors and a small but reasonably active Jewish community. True: my parents were an oddball couple, my mother having been raised in an observant Jewish household. To survive in retail, my father needed to keep the store open on Shabbat, but while he minded the store, my Mom and the rest of us observed Shabbat according to Orthodox practice.

Downtown Sarnia in the 1970s. Via the Sarnia Historical Society.

With the exception of the rabbi, who changed every few years or less and often wasn’t even a rabbi, we were the only observant Jewish family in town. But as my siblings grew older, my parents began to despair of their chances of being able to impart a sense of Jewish commitment to their kids in the absence of a broader Jewish community. They grew frustrated with the limitations of small-town life when it came to Jewish education.

When my grandmother and then my grandfather passed away, my father struggled to gather together a daily minyan to say Kaddish. On Simchat Torah the year my grandfather died, my father took my older brother to synagogue for services, only to find that they were the only two people who had shown up for the minyan. Right there and then, my father decided that enough was enough. They would have to make a move.

And that was what they did.

They sold the house, liquidated the store, rented out the building, and moved the family three hours away to Toronto. They had no real plan as to where to live or work. All they knew is that they wanted to live in a good Jewish community within walking distance of a synagogue and to send at least some of us kids to Jewish schools.

For my two older sisters, the Jewish school option proved impossible because they had already missed too many foundational years, but my older brother and I were both enrolled that fall in Jewish day schools. My brother was ten years old at the time, so catching up on five missed years of Hebrew and Jewish studies proved to be no simple task. I had it relatively easy. I was only five years old and was able to start at the beginning, in kindergarten.

Still, I had my own difficult transition. In late summer, 1971, after a year of renting a house in a suburb closer to downtown, my parents bought a house uptown, necessitating a transfer right before the beginning of grade one to the northern branch of the Associated Hebrew Day Schools.

Because of the last-minute transfer, the school administration placed me in the only class in the grade that seemed still to have an opening, one which was designated for slower language learners. (Remember: these were the days of unabashed academic tracking with nary a notion of differentiated learning or teaching.) For weeks, I sat in this class where it seemed all we did was utter meaningless monosyllables — Ba, Bo, Bi, Be, Bu. Sha, Sho, Shi, She, Shu —, growing more and more stir-crazy with each passing day.

I will be forever grateful to the teacher of that class, whose name I am sad to say I cannot remember, who had the good sense to call the principal, who then called my parents with the idea that I be placed in another class. The teacher could see that I was bored and that if something wasn’t done soon to get me out of there I’d become an outright discipline problem.

So there I was, early in November in 1970, being escorted down the hall to Mrs. Zuckerman’s class, the “highest class” in the grade. Having spent two months sitting in rows and doing nothing but reading out monosyllabic babble from a maroon-colored Hebrew primer, I now found myself in a room where students sat at desks that were pushed together in clusters of four, where they read and spoke Hebrew to each other and to G’veret Zuckerman in full fluent sentences.

The students in this class had come into kitah aleph (first grade) knowing nothing but a few letters of the aleph bet (the Hebrew alphabet), but within two months, they had managed to acquire the basic elements of Hebrew fluency and literacy. I sat there perplexed and dumbfounded, not understanding a single word and completely at a loss for how I ever would.

The next day my mother, not one to let things simply happen to her kids, marched into the principal’s office to ask Mr. Deutsch whether it made any sense at all to plunk a child who didn’t know a word of Hebrew into a class where the other kids were already reading Hebrew stories. Mr. Deutsch simply smiled and told her that soon enough, I’d be doing the same.

I cannot tell you how it happened, but Mr. Deutsch was right.

A week or two later, I came home from school singing a song first in Hebrew, then in English, then in French:

?איפה הבית ואיפה הרחוב

?איפה הילדה שאהבתי מאד

הנה הבית והנה הרחוב

והנה הילדה שאהבתי מאד

Where is the house and where is the street?

Where is the little girl that I think so sweet?

Here is the house and here is the street

And here is the little girl that I think so sweet.

Où est la maison et où est la rue

Où est la jeune fille que j’aimais beaucoup?

Ici la maison et ici la rue

Et ici la jeune fille que j’aimais beaucoup.

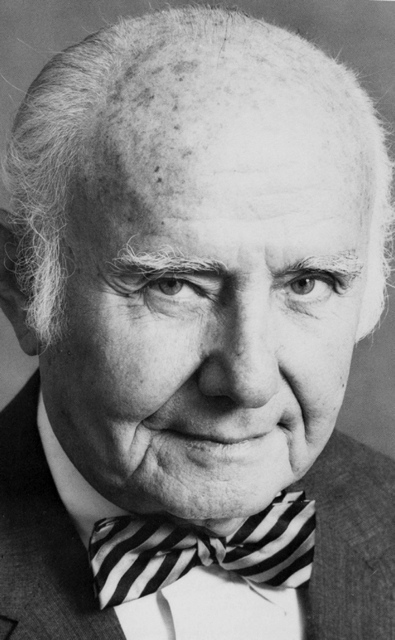

Shalom Secunda, a composer known for his work in the American Yiddish musical theater in the early 20th century. Via the Milken Archive of Jewish Music.

Only later, from my father, did I discover that all three versions were based on Vu is duz gessele, a lament by composer Shalom Secunda and Israel Rosenberg that was itself based on a Yiddish folk song. My father was kind enough not to demand that I tack the Yiddish version onto my repertoire.

I cannot tell you exactly how many times and in front of how many people he and my mother asked me sing that trilingual jingle, but it was a substantial number. There were some in the lot who made it their business every time they saw me to ask me to sing it again.

Perhaps it was because my parents had given up a business and made that epic move from small town to big city, and because it had all been for the sake of Jewish education, that they took such pride in their youngest daughter belting out this ditty in three languages over and over again about a house, a street, and a beloved girl. No matter that the Yiddish original was about the end of the Eastern European shtetl. My parents had had their own rough year, replete with adjustments, and setbacks as my father, formerly his own boss, now searched for a way to make a living.

Still they had these small victories: a new house on a nice street, and what’s more: a little girl they loved who was learning exactly what they had always wanted her to learn, and Hebrew most of all.

Wendy Zierler is Sigmund Falk Professor of Modern Jewish Literature and Feminist Studies at HUC-JIR in New York. She is the author, most recently, of “Movies and Midrash: Popular Film and Jewish Religious Conversation” (SUNY 2017), which was a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award.