A Bizarro-Superman action figure, with a backwards “S” across his chest. Photo by JD Hancock.

By Forrest Martin

In 1960, Action Comics #263 introduced a new setting to fans of Superman: Bizarro World (also known as Htrae, Earth spelled backwards). On this strange, cube-shaped planet, much is eerily familiar, but entirely backwards from the world that Superman knows. The Bizarro Code sums it up: “Us do opposite of all Earthly things! Us hate beauty! Us love ugliness! Is big crime to make anything perfect on Bizarro World!”

Bizarro Superman is the quintessential inhabitant of the planet: he is strong and flies like Superman, but he is immoral, stupid, and Kryptonite strengthens him rather than being his one weakness.

Bizarro World and its inhabitants can actually tell us a lot about the (or really an) America of the 1960s. DC Comics’ portrayal of a world turned upside down reveals its writers’ own value system and presuppositions about normalcy and goodness. The writers saw their own society as basically good and morally upright, as demonstrated by their imagining an “opposite world” as fundamentally wrong.

Such a “symbolic inversion” (as Barbara Babcock dubbed it) that “contradicts, abrogates, or in some fashion presents an alternative to commonly held cultural codes…” is an inadvertent mirror of our own world and ideals. Because of this, we can discern bits and pieces of how people in the past perceived their societies by looking at their “bizarro worlds.”

In texts, we find a literary device called the “topsy-turvy motif,” that portrays a world upturned. These passages describe a bizarre reversal of normalcy, wherein things are turned “upside down” (e.g., the rich become poor, and the poor become rich).

My research orbits around this motif, observing its form and function within ancient texts. By extension, there is a huge deal that we can learn about ancient cultures through their usage of such a device.

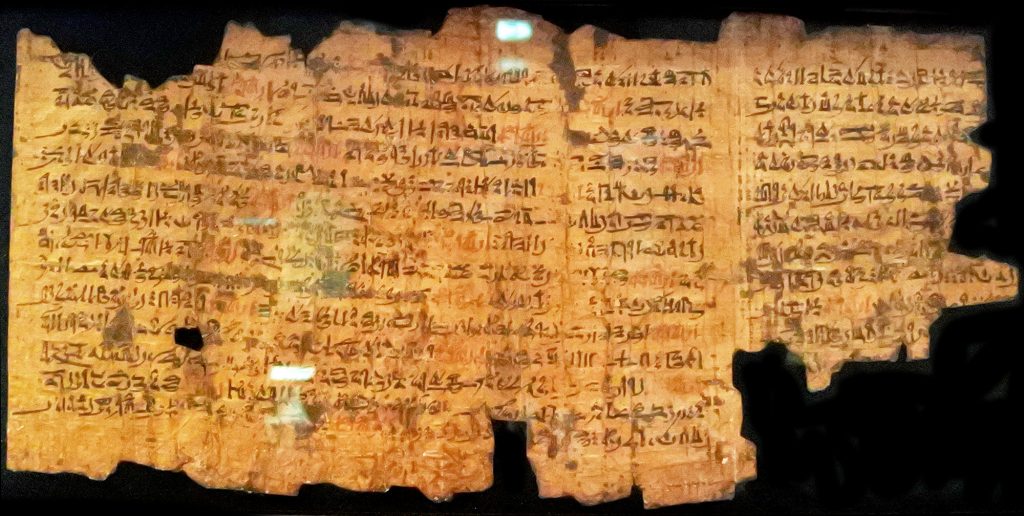

A papyrus containing a fragment of the Admonitions of Ipuwer. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Topsy-turvy in Egypt

The type of bizarre reversal I’m discussing emerged as a literary phenomenon in Middle Kingdom Egypt (roughly 2000-1700 BCE) and beyond. In this period, a few texts (primarily the Admonitions of Ipuwer, a text popularly discussed on account of its parallels with the Ten Plagues, and the Prophecies of Neferti) use this motif to reaffirm the status quo, asserting that social inversion was a sign of chaos infecting the good order of Egypt. This was often connected to the idea of divine abandonment; the texts say that “Re [an Egyptian solar god] had separated himself from the people” (Neferti 51).

In short: topsy-turvy in Egyptian texts is a pessimistic reflection on periods of political disorientation (commonly called the First and Second “Intermediate Periods” in the history of ancient Egypt). The reader or listener is invited to reject such a reversal and maintain the usual state of affairs. The texts highlight the chaos and ill-fitting positions that people now find themselves in because of the reversal: “Behold, the one who hears is (now) deaf, (while) the mute one is in front” (Neferti 37-38). This mostly reaffirms what is already known about ancient Egypt: it was a highly stratified society that valued order (ma’at in Egyptian) above all else.

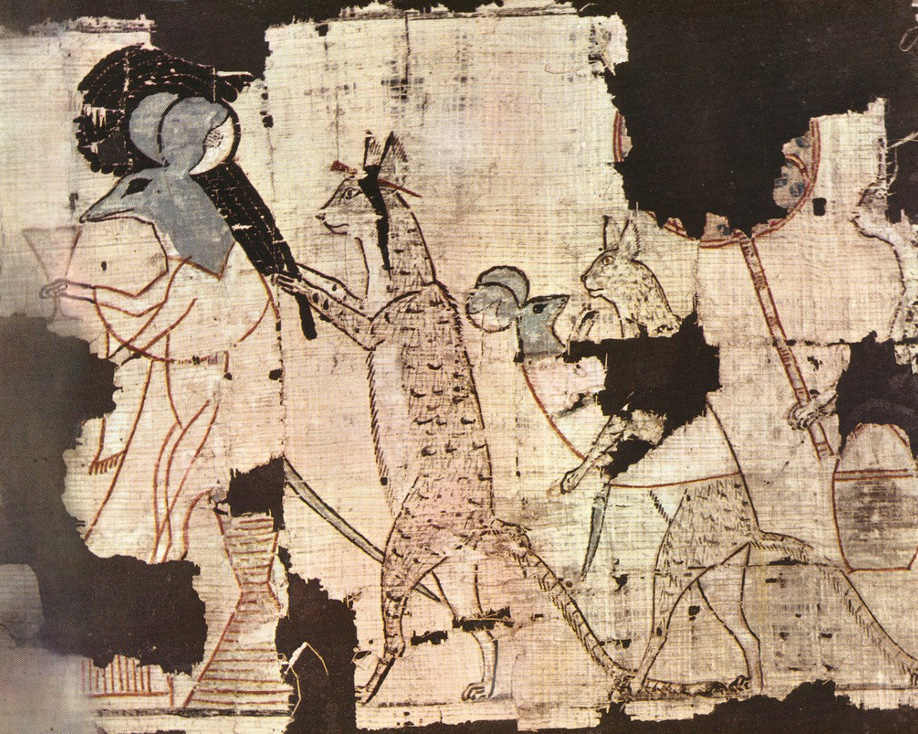

An Egyptian papyrus depicting cats serving mice, circa 1200 BCE. Via the Egyptian Museum (item #2An.013.1a).

Yet, by looking beyond the texts, we see that non-elites may have relished the idea of social inversion. A series of ostraca — pottery fragments with writing or images on them — and papyri depict a positive bizarro world, wherein cats now serve mice as anthropomorphized servants!

These likely reflect a desire of the common people for the disturbance of social order, hence their being based in images rather than texts. This shows us that not everyone was satisfied with the way things were, which is a position quite like that of biblical authors.

Topsy-turvy in biblical Israel

Perhaps the quintessential social inversion from the Hebrew Bible is in Hannah’s Song in the Book of 1 Samuel (1 Samuel 2:4-8):

The bow of heroes is shattered,

and those who stumble gird up with power.

The satiated have (now) been hired out for food,

and the hungry have fattened up.

Until the infertile has borne seven,

and the one abundant with sons has dwindled away.

The Lord brings death and life,

pulls down to Sheol and raises up.

The Lord dispossesses and enriches,

abases and extols,

He raises the poor from dust,

from waste piles he lifts the needy

to make them sit with nobles,

and has them inherit a throne of honor.

For the pillars of the earth belong to the Lord,

and he has placed the world upon them.

Here, Hannah celebrates (in anticipation) a topsy-turvy world, one in which God reverses fortunes — those on top are brought down, while those on the bottom rungs are invited into comfort and power. All these reversals are attributed to her god, who has absolute freedom to change a person’s situation for the better (or worse). So, for Hannah, social reversals are not a sign that God has abandoned his people, but a sign that he is faithful to them. The world she inhabits is already off-kilter, and so a reversal would result in the world being put right.

This passage is characteristic of much of the Bible’s prophetic sentiments. That is, transformation is good, of divine source, and necessary for the here-and-now as well as for the distant, idyllic future (since Hannah’s song, with its royal imagery, anticipates the rise of the monarchy that takes place in the rest of Samuel). The low should be lifted up, and the haughty should be brought low. In other words, “upward mobility” is fundamentally good. This is more reminiscent of the cat-and-mouse ostraca than the motif in Egyptian texts. So while the form of the motif remains largely the same, its function is entirely upended.

However, the Hebrew Bible speaks with many voices and from many perspectives. I offer here one Israelite text among a very small number that create a dissonance when it comes to the “topsy-turvy.” As he does on so many topics, Qoheleth (the orator of the book of Qoheleth/Ecclesiastes) speaks with the voice of a provocative dissenter (Qoheleth 10:5-7):

There is a disaster I have seen under the sun,

like a mistake that goes out from before the ruler:

The moron is placed in many high places,

but the affluent sit in lowly places.

I have seen slaves upon horses,

yet officials walk like slaves on the ground.

Qoheleth views the reversal of social order in certain terms: it’s a “disaster,” or “evil” (raꜤah in Hebrew). If we were to ask Qoheleth what the “reverse” of a slave is, he responds, “an official!” Fair enough; this comparison resonates with the rest of the biblical texts. What about the “reverse” of a rich person? “A moron, a fool,” grumbles Qoheleth.

This stands in stark contrast to such a “reversal” in the biblical prophets, wherein the rich serve as an amoral foil for the poor, hungry, and afflicted. For Qoheleth, those on the lower rungs of society are fools. This betrays his elitist view of the world, and by extension something about the culture of ancient Judah during the time of his writing (around the 4th century BCE during the Persian Period). A reversal for Qoheleth spells personal disaster, since someone like him has everything to lose. Because of this, Qoheleth’s deployment of the topsy-turvy motif has more in common with its usage in Egypt a millennium earlier than with his fellow biblical authors.

Topsy-turvy as a reflection of the world that is

When someone imagines a world upturned, they are really reflecting on their own world from their own perspective. The textual and iconographic data from ancient Israel and Egypt shows us that people of different times and societal standings related to the idea of reversal very differently. They creatively reversed common ideologies of their own time and place to make sense of life’s absurdity.

As medieval Spanish philosopher Balthasar Gracian so eloquently said: “The things of this world can be truly perceived only by looking at them backwards.”

Forrest Martin is a second-year M.A. student and teaching assistant in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilization. He received his B.A. summa cum laude in Hebrew Bible and Ancient Near Eastern studies with a second major in Greek from the University of Washington. His academic interests include a variety of ancient Near Eastern and Mediterranean languages and literatures, particularly as they relate to ancient religion and conceptions of cosmology. As a 2021-2022 Stroum Center graduate fellow, Forrest is researching utopian and dystopian texts’ use of dramatic and unusual reversals, especially those found in the Hebrew Bible.

Forrest Martin is a second-year M.A. student and teaching assistant in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilization. He received his B.A. summa cum laude in Hebrew Bible and Ancient Near Eastern studies with a second major in Greek from the University of Washington. His academic interests include a variety of ancient Near Eastern and Mediterranean languages and literatures, particularly as they relate to ancient religion and conceptions of cosmology. As a 2021-2022 Stroum Center graduate fellow, Forrest is researching utopian and dystopian texts’ use of dramatic and unusual reversals, especially those found in the Hebrew Bible.