Students at the Hand in Hand School in Jeursalem. From Qantara’s profile of the school.

By Rob Keener

I have been interested in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict since I was an undergraduate. As my academic interest has shifted towards education, so has my research focus. Part of my research here at the UW is on how to foster positive intergroup relations across cultures. As a PhD student in Multicultural Education who focuses on teaching the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, I was interested to hear a powerful firsthand account about bridging cultures in Israel.

I first met my friend Afnan Boutrid in a Human Rights and Education class that we took together at the UW. Afnan’s experience as an intern at Project Harmony with the Hand in Hand School in Jerusalem demonstrates the possibilities of teaching for peace through intergroup education, while contrasting that with the real-world societal barriers that often get in the way.

Afnan is a life-long observant Muslim, and she taught at an Islamic school in North Carolina for two years before earning her MA. At the school, she encountered anti-Semitism that often focused on Zionism, which many students saw as the primary characteristic of Jewishness. But Afnan observed how a service project between a Jewish Day School and her school helped her students to decouple the notion of Zionism from Jewish identity.

Afnan was inspired to earn her Master’s in Peace Education at Columbia Teachers College and was influenced by the work of Zvi Bekerman, a notable education scholar at Hebrew University who researches peace education pedagogy and its processes in Israel.

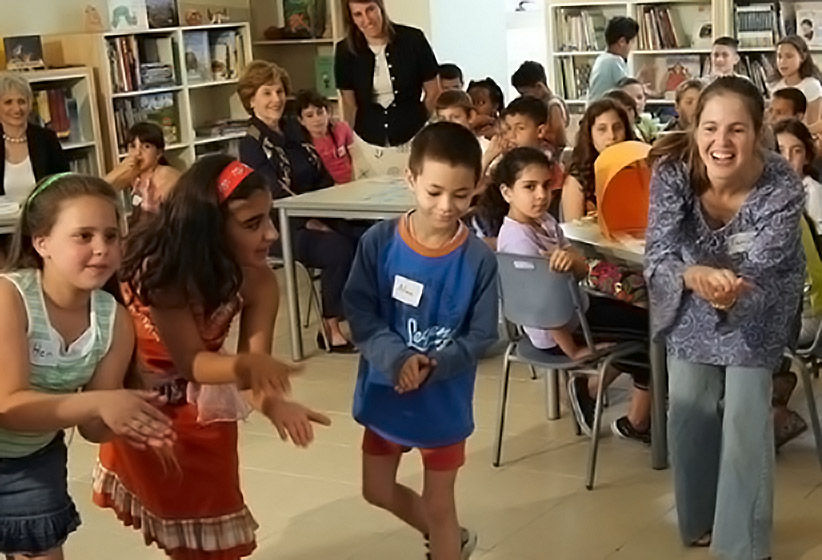

Students of the Hand in Hand School perform a Jewish-Arabic dance. From the White House archive.

With her experiences teaching at an Islamic school and her passion for peace education, Afnan selected Project Harmony for her 2013 summer internship. Project Harmony is an Arab-Jewish summer camp in Jerusalem that seeks to promote positive relationships amongst Israeli youth of all ages through high school. According to Afnan: “The camp was split 50/50 between Arab and Jewish students but was very diverse. Some students were settlers’ kids and had not spent much time with Palestinian people. Some kids were from liberal-progressive families. Some were Arabs who had not spent much time with Jewish children.”

What Afnan saw and interacted with at the camp is a testament to how to create a positive environment where relationships between individuals from opposing groups can occur and prejudicial attitudes can be reduced. According to Gordon Allport’s classic work on creating positive intergroup relations, The Nature of Prejudice (1954), educators can foster positive relationships between students of different groups by allowing them to interact positively (“intergroup contact”). This can diminish prejudice, so long as the positive environment is supported by authority figures, individuals from different groups have equal status, and common goals exist between students.

At Camp Hand in Hand, the kids made quick friendships and spent time learning about each other and developing positive conceptions of one another’s diverse cultures. Afnan saw kids of both backgrounds drawing the Israeli and Palestinian flags, and the students learned each other’s languages: “Young Muslim and Jewish kids took such joy learning to write both in Hebrew and Arabic.”

Students of the Project Harmony summer camp

“Jewish kids took the hand of their Arab friends and told them they were not going to leave their side and would protect them if anything happened. … The school was a sanctuary where the students could escape their social pressures … a place where they could just be kids.”

Camp Hand in Hand serves as one example of how intergroup friendships can occur when the right conditions are in place: relationships were sanctioned by authorities (parents, teachers, administrators), all youth were given equal status, and students shared common goals as campers. Students were able to claim their positive intergroup identity – as Hand in Hand campers – as a means of rejecting the social norms in the region that keep people separated.

However, what is disheartening about Afnan’s story is how much outside social pressures worked against the progress that Project Harmony made. The summer camp was safe space for many students, where they did not have to face the day-to-day pressures of life in Israel: the large presence of security forces in public spaces, the effects of cultural segregation, and regular missile drills.

Nevertheless, this sense of security changed when the older Jewish students came to the camp dressed in military fatigues right before their mandatory military service was set to begin following their final year of high school. This sign of outward social forces – Arab citizens of Israel are not conscripted to the military, while Jewish citizens are – immediately sowed divisions between the older Israeli and Arab students: “When the older kids came in their uniforms, the whole attitude of the school changed and became more socially segregated.”

Afnan came to Israel with the notion that it was a beacon of democracy in the region and left with the feeling that it was more of an “ethno-democracy” that used a variety of unjust structures – expanding Jewish settlements in the West Bank territory, a growing number of security walls, and social segregation – to maintain itself.

However, her time with the campers at Project Harmony has given her hope that peace is attainable if we want it, especially if we can work in schools to promote positive intergroup relationships.

There is a lot of research on how to promote intergroup friendships by scholars such as Gordon Allport, Thomas Pettigrew, Janet Ward Schofield, and Walter and Cookie Stephan. Since Allport published The Nature of Prejudice in 1954, theories of peace education have been tested and have achieved positive results.

The knowledge of how to teach kids from opposing groups to get along and grow together as a society exists, and Afnan believes that kids want it. It is the social world outside of them that continues to drive them apart.

Robert Keener was born in Houston, Texas, where he attended St. Thomas High School and Texas Tech University. After college, Robert spent two years working in the oil and gas industry in Houston before academia came calling. He attended Ole Miss in Oxford, Mississippi, where he took two courses on the history of the Middle East that sparked an interest in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The multi-sided presentation of the conflict by his mentor, Dr. Nikolas Trepanier, was far different than the single-sided polemics that he had previously heard. While at Ole Miss, Robert focused on studying systems of oppression such as apartheid, Jim Crow and imperialism. After earning his MA in history, Robert enrolled in the University of Washington’s Multicultural Education doctoral program, where his research centers on teaching controversial topics in social studies, global citizenship education, and the construction of knowledge. When he is not working as a research assistant at the Center for Multicultural Education or trying to earn his doctorate, Robert enjoys hiking in the mountains with his wife Emily and their chocolate lab named Rylee.

Robert Keener was born in Houston, Texas, where he attended St. Thomas High School and Texas Tech University. After college, Robert spent two years working in the oil and gas industry in Houston before academia came calling. He attended Ole Miss in Oxford, Mississippi, where he took two courses on the history of the Middle East that sparked an interest in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The multi-sided presentation of the conflict by his mentor, Dr. Nikolas Trepanier, was far different than the single-sided polemics that he had previously heard. While at Ole Miss, Robert focused on studying systems of oppression such as apartheid, Jim Crow and imperialism. After earning his MA in history, Robert enrolled in the University of Washington’s Multicultural Education doctoral program, where his research centers on teaching controversial topics in social studies, global citizenship education, and the construction of knowledge. When he is not working as a research assistant at the Center for Multicultural Education or trying to earn his doctorate, Robert enjoys hiking in the mountains with his wife Emily and their chocolate lab named Rylee.