Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Ambassador to China Matan Vilnai and entrepreneur David Leb with a representative of a Chinese investment fund on a 2013 visit to China. Photo from Eco Wave Power.

By Sam Gordon

The election of Donald Trump, coupled with the increasing influence of non-Western powers like Russia and China, underscore a significant shift occurring in the world order. We are moving from a unipolar world order dominated by the United States to a multipolar world order where non-Western powers exhibit an ever-increasing influence on global affairs. Within this context, paradigms and alliances are bound to shift, and Israel’s “pivot to Asia” is a notable example.

During a 2017 visit to Singapore, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced that Israel intends to expand relations with Asia in a very purposeful way. The Jerusalem Post asserts that this realignment is based on Israel’s assumption that Asia will eventually dominate foreign affairs in the region. The first stirrings of this seismic shift are already being felt across the continent, as Israel grows closer with North Asia (Japan, South Korea, China), South Asia (India, Vietnam, Singapore), and even some Gulf states.

What factors precipitated Israel’s reorientation, and what are the potential consequences of this shift?

Seeking new partners

Israeli flag flies near Tiananmen Square, Beijing, during Benjamin Netanyahu’s 2017 visit to China

Israel’s relations with Asian countries — except for Burma and Singapore, which established relations in 1953 and 1969, respectively — date back to the fall of the Soviet Union. Formal relations with India and China, for instance, began in 1992. A significant factor in Asia’s estrangement from Israel was the Soviet portrayal of Zionism as a product of Western imperialism. Soviet propaganda asserted that Western countries had used Zionism as a pretext to extend their colonial rule further into the developing world. According to Abadi, this conspiracy theory “found many adherents in the Asian countries,” which made establishing diplomatic relations more difficult for Israel.

Economic factors in “looking east”

The growing importance of Asia for Israel runs parallel to its emergence as a major force in the world economy. Today, three of the seven largest economies in the world reside in Asia.

Economics, and more specifically trade, are driving Israel closer to several Asian states, notably China, which engaged in $15 billion of bilateral trade with Israel last year. In fact, China (including Hong Kong) is now second only to the United States as a source of imports to Israel and as a consumer of Israeli exports.

Regional expert Mordechai Chaziza asserts that the Israel-China relationship is built around economic, technological, and infrastructure partnerships. Chinese companies have been steadily investing in Israeli industries such as Tnuva Dairy and Ahava beauty products. Chinese investors, wary of trade disputes with the U.S., may increasingly look to Israel for high-tech investments.

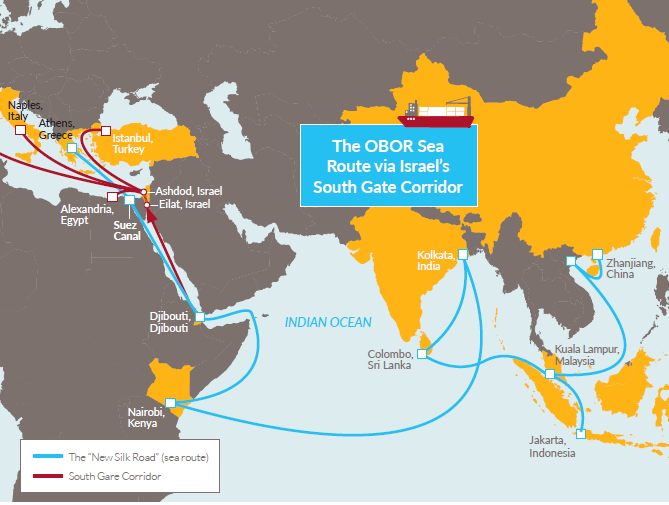

“New Silk Road” sea route

China also sees Israel as a key partner in its One Belt One Road Initiative, which aims to recreate the ancient Silk Road by connecting China with Europe through new land and sea routes. Israel’s strategic proximity to the Red Sea and Suez Canal places it at the center of these ambitions. Chinese investors are also funding the upgrades to the ports in Haifa and Ashdod, as well as a Med-Red railway between Eilat and Ashdod, which will create an overland alternative to the Suez Canal. Chinese investors see a large potential return on investment in these projects, which also cement Israel as avital economic bridge between East and West.

Israel’s reputation as a reliable source of military equipment and a partner in intelligence-sharing is also helping to raise its profile in Asia. Israel is now the second-largest arms exporter for both India and China, and Asia is now the largest arms market for Israel, totaling $4 billion in 2014, compared to $2 billion combined in America and Europe. Israel’s commitment to a “no strings attached” policy, which eschews specific political stipulations as part of any deal, has made it an attractive partner for these countries. Israel is also crucial provider of intelligence for nations facing the threat of terrorism. Israel hopes that helping other nations to combat terror will strengthen its diplomatic relationships.

Political factors

With rising anti-Semitism and anti-Israel sentiment in the West, the Asia-Pacific region is growing in political importance for Israel as well. When Prime Minister Netanyahu visited India this year, he proclaimed, “Jews in India have never witnessed anti-Semitism.” This speaks to the fact that there has been comparatively little anti-Semitism in Asia, a factor that has implications for the political sphere.

Relief workers from IsraAID search for survivors following the 2015 Nepal earthquake

While the prevalence of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement and disagreements over the peace process have reduced relations between Israel and the European Union, and perceptions of excessive military force during the 2014 Operation Protective Edge in Gaza have led to condemnation in Latin America, Asian countries have declined to comment on these issues. This neutral response has encouraged Israel to seek broader and deeper ties in the region. Israel is working hard to increase political ties with Asia through tourism and humanitarian outreach via NGOs such as IsraAID, which has offered significant aid in the wake of disasters following the 2015 Nepal earthquakelike the Nepal earthquake in 2015.

However, viewing these moves as just a “pivot to Asia” is missing the larger picture. While Israel’s relations with the West are waning in some respects, 63% of Israel’s trade is still with the U.S. and Europe. It is more accurate to understand this pivot as part of what Chaziza calls a “strategic hedge” against the West. Israel is, in effect, creating an insurance policy in Asia, reducing the risks of being too closely tied to a single region by pursuing diverse diplomatic opportunities elsewhere. Part of this hedge includes joining new multilateral institutions such as Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB), a World Bank alternative, which Israel formally joined in 2016, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which Israel has applied to join.

Chaziza asserts that China or any other Asian nation cannot become Israel’s chief ally because of the “considerable dependence on the great diplomatic and security-related support [Israel] receives from Washington.” But viewing Israel’s diplomatic strategy as a choice between aligning with either the East or West is misleading. Israel’s geography and culture, and the fact that it identifies with the West while residing in the East, makes it uniquely placed to act as a bridge between these two hemispheres.

Sam Gordon is the Stroum Center’s Rabbi Arthur A. Jacbovitz Fellow, and is currently a first-year master’s student at the Jackson School for International Studies, concentrating on the Middle East. He is from Florida and attained a bachelor’s degree in 2014 from Florida State University majoring in History and International Affairs. After graduation, Sam moved to Jerusalem and worked as a research assistant at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. He conducted research on topics including diplomacy and human rights in the Middle East. He also spent nine months living and working in Prague, where he absorbed a great deal about Jewish communities of Central Europe. For his Graduate Fellowship project, Sam plans to investigate the role Israel will play in the newly forming international order as well as the challenges and opportunities it faces on a global scale. His research interests include Israeli foreign policy, geopolitics of the Middle East, and the intersection between technology and foreign policy.

Sam Gordon is the Stroum Center’s Rabbi Arthur A. Jacbovitz Fellow, and is currently a first-year master’s student at the Jackson School for International Studies, concentrating on the Middle East. He is from Florida and attained a bachelor’s degree in 2014 from Florida State University majoring in History and International Affairs. After graduation, Sam moved to Jerusalem and worked as a research assistant at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. He conducted research on topics including diplomacy and human rights in the Middle East. He also spent nine months living and working in Prague, where he absorbed a great deal about Jewish communities of Central Europe. For his Graduate Fellowship project, Sam plans to investigate the role Israel will play in the newly forming international order as well as the challenges and opportunities it faces on a global scale. His research interests include Israeli foreign policy, geopolitics of the Middle East, and the intersection between technology and foreign policy.

Antisemitism has existed in Europe for approximately 2000 years, and whenever Europe has experienced hardships and upheaval, such as for instance the two world wars, the bubonic plague during the 14th century, the Wall Street crash in 1929 and so on, Antisemitism always rears it ugly head!

Israel is wise to look for allies and partnerships in the Asia region, and not to rely too much on the Christian West!

Right now Antisemitism is on the rise again in the West, thanks to the Corona virus pandemic and the ensuing violence and social chaos in its aftermath, which is quite predictable of course!