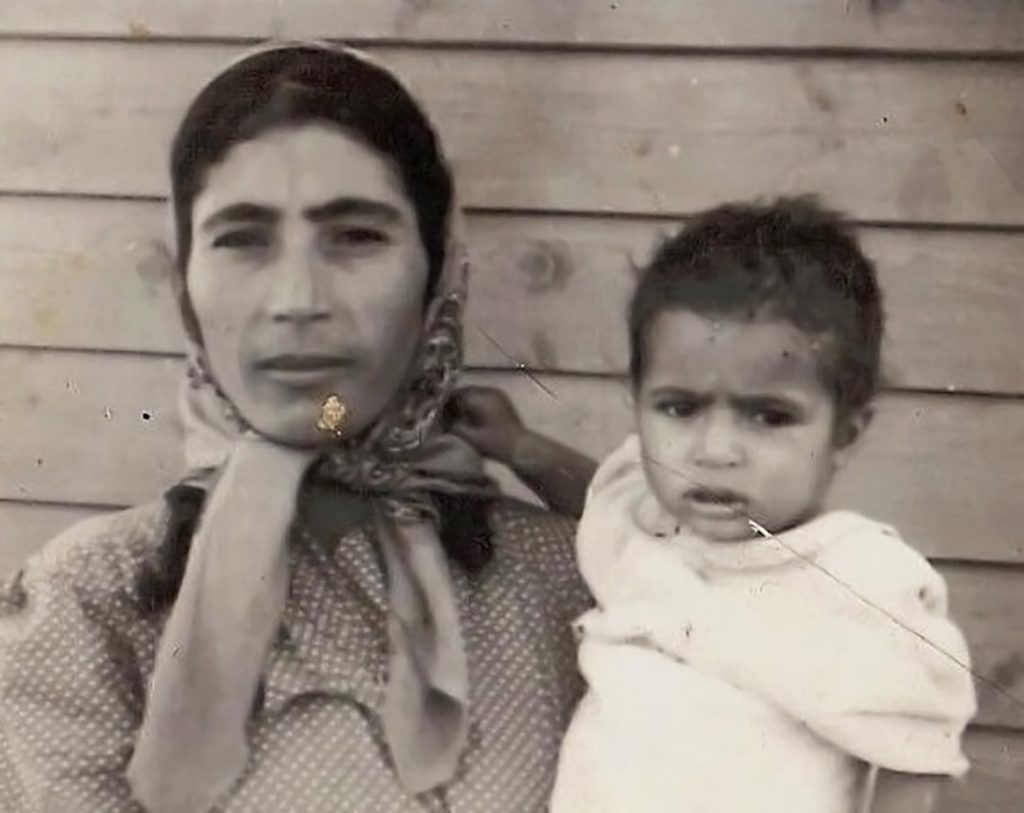

A Jewish Yemenite family in transit to Israel in 1949, part of the mass migration of Yemenite Jews to Israel in 1949-50. From the National Photo Collection of Israel.

By Vincent Calvetti-Wolf

They tried to kidnap my uncle right after he was born. The nurse came in to tell my grandmother that her baby didn’t survive. My grandfather, who had the ability to be very scary when he wanted to, was not convinced. He went over to her and yelled: “Where is my son?!” and was both mad and loud enough to make the Ashkenazi nurse return his son.

–Testimony of Roy Grufi

Many accounts have been written about the large waves of immigration to the State of Israel following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, when Jews from across the Middle East and North Africa immigrated to the new state. Less known is the fact that during those early years, several thousand babies and young children went missing. Nearly all of these children were born to families of recent immigrants, living in the poorly maintained and isolated absorption camps where they were settled by state authorities upon their arrival.

Around two-thirds of the missing children were from the families of immigrants from Yemen, according to Amram, an organization dedicated to documenting and raising awareness of what has come to be known as the “Yemenite Babies Affair.” Every eighth child of a Yemenite family went missing, while “the remaining third of the children were from other Mizrahi families – Tunisian, Moroccan, Libyan, Iraqi and others – and a small number were children of families who immigrated from the Balkans.” A small number of missing children from Ashkenazi families have also been documented.

My sister Rachel was three months old. She had a fever, so my mother took her from Nahariya to Rambam Hospital in Haifa. We lived in a shack in the transit camp and my parents didn’t speak any Hebrew. There was transportation only once a day. My mother went to visit her after a week and found her healthy. She wanted to take her home, but she was told to come back in two weeks. A week later she received a letter saying that the baby died. She asked to see a body, but there was no body. Eighteen years later an army draft notice arrived.

-Testimony of Herzel Doniari

In many of these cases, a common pattern emerged. From Shoshana Madmoni-Gerber’s book “Israeli Media and the Framing of Internal Conflict: The Yemenite Babies Affair,” a “typical scenario was as follows: a baby was taken to the hospital despite parental assertions that the child was healthy. The baby was then taken to one of several institutions around the country, such as Wizo, an international women’s organization with centers in Safed, Jerusalem, and Tel Aviv. The parents were told that their baby had died.”

Shulamit Arami holding her daughter Mazal. Arami lost a newborn daughter in 1954.

In some cases, a child who was said to have died was later returned to their family when a parent made enough of a disruption. In other cases, parents were told their child had died and been buried by hospital staff, with families never shown a burial spot or death certificate. And in others, nurses have testified that they thought they were “doing the family a favor” by finding another, more well-off family to adopt their child. As a result, many families of missing children have accused establishment-linked hospitals and clinics of systematically kidnapping their children and giving them to Ashkenazi families in Israel, Europe, and the United States.

Madmoni-Gerber describes how assertions by families with missing children were dismissed in the media, often by dismissing the families as misled by superstition or urban legend. Quite often, a family’s background as Mizrahi Jews — those Jewish communities with ancestral roots in the Arab and Muslim world, widely acknowledged to have faced structural racism at the hands of a largely European, Ashkenazi establishment during the first decades of the state of Israel — was referenced to discredit these testimonies.

Public conversation around the affair changed in December 2016, when Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu, in response to growing pressure, announced that he was ordering the Israeli State Archives to declassify 210,000 files from government inquiries into the disappearances — records that were originally scheduled to be de-classified only after 2071. Netanyahu described this decision as “fixing today an historic injustice, of ignoring, of disappearance and of discrimination… We don’t know what the fate was of the Yemenite children. For close to 60 years, people have not known of the fate of their children. We are not prepared for this to continue, which is why we decided on transparency and justice.”

Since then, members of the Israel’s legislature, the Knesset, from as far left as Tamar Sandberg of the Left Wing Meretz Party to as far right as Naftali Bennett of the Right Wing Jewish Home Party, as well as members of the Arab Joint List like Jamal Zahalka, have called for official recognition of the kidnappings.

Certain things you feel whether they are true or not with a clear gut feeling. The power relations in that generation did not allow them to raise their voice, but little by little the grandchildren wake up and demand answers–and if not answers, at the very least memory.

-Testimony of Shlomi Hatuka

My previous research on groups like the Israeli Black Panthers had made me deeply aware of the ways that social movements need to constantly find innovative and creative new ways to maintain strong connections to their audiences in order to maintain momentum for work that can often take years to bring to fruition.

Long interested in how social movements build the capacity for social change, my research looks at the ways social media has transformed how activists can educate and mobilize the public. By using Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube to share personal testimonies of the families of kidnapped children, groups like Amram can take their cause straight to the people in a way never possible before.

Protestors in Jerusalem on June 2017. Photo by Emil Salman, from the Haaretz newspaper article covering the event.

Such potential was evident this past June, when Amram called for activists to demonstrate in support of the families in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. Many families showed up and shared the stories of their children’s abduction publicly for the first time while activists blocked traffic, creating a new public space for these narratives.

More personally, I have been surprised by how many people in my own life have been affected by this issue. Upon hearing of my research, friends, Hebrew teachers, and sometimes even strangers have confided in me the pain and heartbreak a disappearance had caused their families. While this has been treated as an exclusively “Yemenite affair,” it’s important to note the deep societal effects of such a widespread event. Even the upper echelons of Israeli society has not been exempt — a fact driven home when it was revealed that Israel’s former President, Moshe Katsav, is among those seeking to discover the truth of his brother’s mysterious disappearance as a child.

He was informed that the child had died; he couldn’t understand how such a minor injury caused a young child to die in one day. My grandfather, who didn’t know local customs and spoke only Yemenite Arabic and according to my uncle Yitzhak was still in mourning over the passing of his wife, was returned to the camp and did not inquire any further. Just like in so many similar stories, there was no body and there was no grave. But years later, as they found out, the child’s military conscription order arrived at their doorstep.

-Testimony of Tal-Zahra Lavie

As I conducted my research, I have been startled to find that the problem of the trafficking of children of marginalized communities is not limited to one country or government. From Ireland to Argentina to Canada to Appalachia, the kidnapping and trafficking of children from marginalized communities is a global issue that demands a global response.

The struggle by Yemenite, Mizrahi, and Balkan families in Israel to continue to demand justice, in spite of decades of denial and dismissal, and the innovative methods they have used to successfully transform the way the public thinks about these disappearances, have much to offer other activists working on similar issues in their own countries.

Vincent Calvetti-Wolf is a first-year student in the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Interdisciplinary Ph.D. Program. He holds a B.A. in Liberal Arts from The Evergreen State College and obtained a Master of Arts in International Studies, with a focus in Comparative Religion, from the University of Washington in 2017. His research explores the histories and politics of social movements led by Mizrahi Jews in Israel. His current project focuses on the strategies used by grassroots movements in Israel to raise awareness about the Yemenite, Mizrahi and Balkan Children Affair that took place in the early 1950s. Vincent is graduate student co-coordinator of the Israel/Palestine Research Colloquium.

Vincent Calvetti-Wolf is a first-year student in the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Interdisciplinary Ph.D. Program. He holds a B.A. in Liberal Arts from The Evergreen State College and obtained a Master of Arts in International Studies, with a focus in Comparative Religion, from the University of Washington in 2017. His research explores the histories and politics of social movements led by Mizrahi Jews in Israel. His current project focuses on the strategies used by grassroots movements in Israel to raise awareness about the Yemenite, Mizrahi and Balkan Children Affair that took place in the early 1950s. Vincent is graduate student co-coordinator of the Israel/Palestine Research Colloquium.

Very well written. Touches on a subject that I know nothing of but was very interesting to read.

If there were thousands of “brown” Mizrahi babies being raised by “white” Ashkenazim, it would have been noticed by now – especially in a country as tiny as Israel. The children are dead. They got sick in the refugee camp tents and were given low priority by the Ashkenazi hospital staff. When they died, Ashkenazi bureaucrats thought the Mizrahi parents “all looked the same” and didn’t want to be bothered. Israel should declare the children dead and set up a compensation fund, not that anything can actually make up for what the families have suffered.

To “DMYCCV” – if you would actually read the article, you’d find the author claimed the babies were often given to families in the US and Europe also, not just in Israel. (And that has been the claim of others writing on the subject.) In fact, you do have a point – about those who would have been raised in Israel – but it doesn’t PROVE anything. It’s just evidence contrary to the author’s (and those who believe in this) thesis. I personally have no problem believing it COULD have happened; I have been here long enough to learn how badly Mizrahi families were treated on their arrival and for years afterward. My problem is: after all this time and publicity, why have we not “found” scores of these children? I’d think that many would have questioned their heritage once grown or at least some time down the road and, by now, they’d all be over 50, right? Any time there’s a conspiracy theory, you have to think it all the way through. The vast majority of them fall by the wayside with some thought and research. I am sympathetic to this one but I really think we need to meet – publicly – at least a handful of these folks.

Hi David, thank you for your comment. You might be interested in the oral histories from people affected by this event that are available via the Israeli organization Amram. Here is the link: https://www.edut-amram.org/en/categories/all/

I’m a Yemeni American my grandparents told me our neighbors were Jewish in the village in yemen and when they left to Israel they all cried that they were leaving their home and us Muslim neighbors my grandparents were crying too they told me they were like family and I feel very sad that when they arrived in Israel they were treated bad and had their babies taken . May god be with them and protect them from wrong

To me, these are the real Jews.

💯% right. And a pristine biblical tradition.

Ashkenazim constantly lump Sephardic Jews in with Mizrahi Jews because it seems they don’t consider it worth learning about the differences.

But far more pernicious is the way the Ashkenazi Left treats Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews. Left wing Ashkenazic Jews often accuse Sephardic and Mizrahi progressives who don’t toe their line point-for-point of being fake progressives, “posturing as people of color” or, just like in when familys arrived from the Ottoman Empire, they tell those of us from brown countries that we’re ignorant or backwards.