African protesters and supporters gather at Tel Aviv’s Levinsky Park on Tuesday (photo credit: AP/Ariel Schalit)

By Oded Oron

According to the United Nations Commission for Human Rights (UNHCR) an unprecedented 65.3 million people around the world have been forced from their homes and nearly 34,000 people are forcibly displaced every day as a result of conflict or persecution.

One of the most rewarding aspects of my job as a researcher and scholar is the chance to interview migrants, listening to their story and learning about their journey. Hearing firsthand from migrants about the circumstances that forced them to flee, their incredible resourcefulness and unbelievable courage, inspires me to document it, talk about it and act in order to change this man-made reality.

It is often said that only when making a story personal it can truly penetrate our minds and hearts. The following story is of Oscar Olivier, a 50-year-old asylum seeker from the Belgian Congo that recently arrived to the U.S. with the intention of finally receiving fair protection and permanent status. Oscar’s journey is unique and his personal account brings together the story of freedom, justice, resistance, rights and embracing of his Jewish past.

[Editor’s Note: This interview was conducted in Hebrew and translated by Oded Oron.] Let’s start from the beginning. Please tell me about yourself: Where are you from? Where did you grow up?My name is Oscar. I was born in 1967 in what is today known as the Belgian Congo. There wasn’t always used to be two separate places but as you know, when Europeans came to the region, they draw a line on the ground and divided it arbitrarily based on their needs. It is the same people, same culture, but now two different nations. In the 1960s, when decolonization began, a president rose to power. He was succeeded by a dictator, and now it is also ruled by a dictator. We have a constitution but it is not really implemented.

But going back to my own story, I was born in Kasai, in the center of the country about 560 miles from the capital Kinshasa. I was born to a very young mother—she was 17-years old when she had me, my father left when I was very young and due to these circumstances, I was raised by my grandmother.

My mother was born in Angola. Her dad was of Portuguese origin and had Jewish roots, his ancestors were expelled during the Spanish Inquisition from Portugal, and her mother was African. Because of this mixed ethnicity and her skin tone, my mother was rejected by the Europeans for not being European enough and by Africans for not being African enough. My grandmother decided to move to Congo with the hope that my mother would be more accepted there. My grandmother learned a lot from the Portuguese colonialists about organizing a society. She developed knowledge of the law, about rights, and about social and political hierarchy; charged with that knowledge she quickly became a central figure as a mediator in our neighborhood. I remember as a child, people coming to my grandmother to pour their hearts and complain, seek advice and resolve disputes. You need to understand that this is very unusual for a woman in African society, particularly in Congo; such a task of arbitration was done by Belgian colonists not by an ordinary local woman. It was through this context that I developed my social and political consciousness and the desire to engage socially and politically.

Did you ever ask her what inspired her?

Not really, I was too young, but reflecting on these experiences I later realized just how inspiring she was. If we were to walk 10 yards, just to cross the street, that could take us 15 minutes, every opportunity someone would stop her and seek her help. When thinking about my own activism, [I consider] her amazing qualities [that were] passed on to me, for example, I remember mediating between kids of different tribes at school.

Can you tell me about the circumstances that forced you to leave?

After high school, I enrolled in the school of architecture. I served as a student representative of the school and that put me in conflict with the local government there. Corruption is a common practice in Congo. A good example is the foreign aid given by international NGOs to support students – that money never reaches the students. As a student representative of the school in 1994, I asked to meet with the minister of education to find out what was happening with the funds. Congo only has three academic institutions, so people come from all over the country in order to go to school, forcing them to live close to campus. A scholarship for them is like oxygen, it helps to cover books costs, transportation, housing, everything. We organized together, several student representatives and demanded to meet with the minister. Of course, our request was stalled intentionally: a date would be finally set and then the appointment would be cancelled with excuses. As students we were getting impatient. We organized a rally, a non-violent protest, but when acts of civil disobedience occurred, the state-run media labeled it as a provocation by students trying to build a political career.

What kind of actions did you take?

We would march, block roads and uses those type of means in order to protest. My involvement as an official student body representative enabled the government to have all the information on me, my name, my whereabouts and where I live. Look, it is hard to understand, but Congo is a dictatorship, and as such, the government has spies everywhere. Whether it is the bank or the post office, even certain classes [at school], people would be there, taking notes, monitoring and reporting to the officials about what is going on. The flip side of it is that as a student body representative, I would engage in active resistance, questioning what is going on. People like us would become an outlet for senior people, bankers, industry men, even the headmasters in our school—an outlet [upon which] to express their grievances. I never realized how powerful of a position it is but that power is also dangerous. You are tempted to think you are invincible, [but] soon I learned just how much risk I was taking.

Was there a moment or incident that changed the circumstances and made you realize you can no longer stay?

Yes, absolutely. I used to work as a substitute teacher in a local high school, teaching math. One night, as I was walking home, I was attacked by a group of men. Later I learned those were policemen but they were not wearing their uniforms. I was stabbed in the chest and waist. I was arrested and beaten, look at my hands—you can see that one my palms is slightly deformed—it is from beating and the nasty breakage I suffered while tortured. Later [when] I was released, I acknowledged I can no longer stay.

Intimidation was a common practice. Often police would come to our school and break our equipment, but that did not deter us. The stabbing incident changed everything for me. I first moved to a friend’s house and stayed in hiding. In 1994, reports by foreign embassies already stated that the police are actually a tool used by the government to repress the people. Egypt was one of the few countries that maintained and even strengthened the relations with Congo and getting a visa was fairly easy. At the time, many Muslims in Congo went to a seminary in Cairo to study and I received the contact information of a Congolese guy in Cairo that took me in when I arrived. That guy told me that the brother of the commander of same unit that was in charge of monitoring students back in Congo was a student here in the seminary. He also said that if you are a Congolese in Egypt you are either a student in that institution or a soldier here for training; he insisted I would stand out and if caught [I’d] be sent right back, and that meant only one possible outcome.

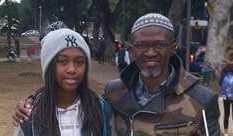

Oscar and his daughter Esther in Tel Aviv

How did you respond, what did you do?

I was scared and frustrated. I spent two more months in Egypt and then thought, in the Middle East, Israel is the only place that is considered a democracy, it is a place of law and that guided me into making my decision. Israel had relations with Congo, mainly because of arms deals. I knew it was possible to get a visa to go there and that is what I did. I applied for a tourist visa and got it. Afterwards, with the little money I had left about $50, I bought a ticket to Tel Aviv.

Nevertheless, when I arrived there in 1994, the issue of refugees was non-existent. There weren’t any refugees in Israel and that issue as a legal category was undeveloped. Even the migrant workers’ community that the country began importing was small and insignificant. The only body that dealt with refugees was UNRWA and I was not a Palestinian. Despite that fact, I wrote them. They didn’t even know how to deal with me but asked for more details and I wrote them back in detail. I was classified by the Israeli authorities as a migrant worker. One of the largest migrant workers’ community in Tel Aviv at the time were Ghanaians. Many worked in cleaning or doing other custodial work. Ghanaians took me in as one of their own, they taught me everything—how to get around, how to find work, housing, and in my first days even provided me with food and shelter.

When I think about how Ghanaians were perceived by Israelis at the time, those that knew they existed I mean, they were liked. Ghanaians were known to be very reserved, soft spoken, obedient and docile. There were good relations between neighbors and between them and their Israeli employers.

What did you do for work?

All kind of jobs—restaurants, hotels, cleaning, I worked for whoever would hire me. It was through my daily interactions with people at work that I learned about Israeli culture and developed basic language skills. By the way, at the time, it was forbidden for people like me to enroll in ulpan [a school for the intensive study of Hebrew], so I bought a book and learned Hebrew at home with the help of my employer’s son who taught me the alphabet and basic grammar. Acquiring the language changed my life and daily existence there. You know when you get utility bills or any type of official documents, it is all in Hebrew, and too often not understanding what it said would cost you dearly. I realized that this language barrier is a source for exploitation.

How so, can you give an example?

Sure. My Ghanaian flat mates, no matter how much time they spent in Israel, could never expand their vocabulary beyond basic phrases, not to mention developing reading or writing abilities. By learning Hebrew, I was soon able to translate for the community, become like a spokesperson and help them, for instance, figuring out the electricity bill. There were too many occasions when Israeli landlords that [owned] more than one property would send us a higher bill and we would end up paying it since we couldn’t read the bill. Learning Hebrew was the start of my liberation, it enabled me to pursue my rights and seek asylum.

Tell me what you did?

I quickly realized that I was caught in limbo. The Israeli government does not know how to deal with me and I didn’t know the language or the structure and did not know how to pursue my asylum case. One day, a friend of mine in Belgium told me that UNHCR has a unit in Tel Aviv and that I should try to find them. These were the pre-Google days I remind you, and it was not an easy task. In 2000, I wrote a very detailed letter to UNHCR. They reviewed my case and I received temporary protection for the first time—a temporary permit that I had to renew every six months.

At the same time, I gained status in the community. My language ability enabled me to be like my grandmother, an organizer and mediator for those who face barriers and have problems.

Were you involved in formal organizing?

Absolutely. My language skills offered me an opportunity to be the voice of the community, or I should say communities. My engagement in politics reached the peak in the early 2000s when I was involved in the protest to stop mass deportations of undocumented labor migrants in Israel and more specifically, to get status for children of migrant workers. I met the mother of my child in Israel, a South African woman [who] worked in Israel; my daughter Esther was born in 2003. It is true that I had a personal interest, since Esther was facing deportation, but it was a matter of justice and lending voice to those who are invisible in Israeli society [as well]. I was on reporters’ call-list every time they needed an “African” representative; I even met and told my story to the Minister of the Interior.

Oscar holding a Torah in Tel Aviv

There are many non-Jewish migrants living in Israel but almost all of them don’t even consider converting and if I am not mistaken you have to be a legal resident in order to even ask for it. What inspired you to convert to Judaism?

You know, considering my track record with the Orthodox-run Ministry of the Interior in Israel and the insults I received from bureaucrats, most notably by former minister Eli Yishai, that sees the presence of non-Jews in Israel as a threat to the integrity and identity the state, you would think that conversion would be the last thing I would pursue. But the desire has been in my heart for some time. I knew, however, that without a legal status I [would] not be allowed to begin the conversation process.

It all started in 2011. I was involved in the social protest and was one of the permanent residents in the encampment at Levinsky garden. The encampment chose me to be one of their spokesperson specifically because this encampment has been the bastion of South Tel Aviv residents expressing their grievances—those who are really at the bottom of the social ladder—and I knew this neighborhood and its problems inside out.

One night I was giving a talk and a reporter in the crowed came to me at the end of my talk and gave me his business card. He said he was from Kibbutz Gezer and that he would like to invite me to speak about the reality in South Tel Aviv. A few weeks later he called me and I gave a talk in the local synagogue of their kibbutz. That moment—the energy in that synagogue—the only thing I could think about is that I want to meet the rabbi [to begin the process of conversion]. After we met, she put me in touch with a rabbi in Yafo (in the southwest neighborhood of Tel Aviv) and I began the process [of studying for conversion] with the help of the Reform movement. Over the course of five years, I studied twice a week. It was through these intense, emotional and educational encounters that I learned. You see, every Jew remembers three things: the destruction of the Temple (commemorated as the holiday of Tisha B’Av), the expulsion of Jews from Spain and Portugal, and the Holocaust. I learned about our connection as a people, the meaning of our distinct identity, and most importantly the difference between Judaism—its rich culture—and the interpretation of Judaism used by the Orthodox in Israel as a political tool.

Oscar reading from the Torah in Tel Aviv

My daughter grew up as a full Israeli, both because she grew up in the Israeli school system and also because we practice Judaism at home. At the end of a long struggle, she received permanent residency but she can never become a citizen there. My status remained unclear: I had temporary protection—a permit I have to renew every six months—subject to the Israeli government’s political whims. I felt it was time for me to seek permanent status because the instability of the political system could deprive me of my rights at any given moment. It was important for me to become Jewish, and I knew I couldn’t leave Israel without it.

Today, I am in Washington State. I filled an official asylum application and waiting for my application to be approved so I may finally have a permanent legal status and the opportunity to live with dignity.

What has been your impression of Washington State?

I like it here. People are kind and very polite. Because of my appearance—an African man wearing a big yarmulke—people say to me Salaam Alaikum in the street–thinking I am Muslim. I smile because I am not sure how I am supposed to respond?

Another impression is that American Jews don’t really speak Hebrew. I was so surprised. I remember when I went to the DMV and I saw an Orthodox guy wearing a big black yarmulke, I went up to him and started speaking in Hebrew. He smiled, apologized and said – “I am sorry, I don’t speak Hebrew” so we switched to English.

I was very fortunate to have found a Reform synagogue in the Seattle area where I go to pray regularly. The congregation is very nice and people always ask me to speak in Hebrew. My story is so unusual they have to hear me speak and witness it for themselves–an African Jewish man. My hope is that my status will be cleared soon and then I will be able to learn even more about the community here and to be able to more fully take part in Jewish life here.

Oded Oron

Oded Oron was born and raised in the Tel Aviv suburbs, and his research focuses on the political mobilization of irregular migrants (labor migrants, asylum seekers and undocumented migrants) in Israel and the USA. He holds degrees in Political Science and Communications as well as in Politics and Government, and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in International Studies. Oded was a Stroum Center Graduate Fellow in Jewish Studies in 2016-2017.

For Further Exploration

- Read “Teaching the Politics of Migration” by Oded Oron (Jan. 2017)

- Read Oded’s blog post, ““Native” author Sayed Kashua on Immigrant Identity.”

- Learn more about the Graduate Fellowship at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies

- Read more online articles written by Stroum Center Graduate Fellows

Amazing story you have shared with the community in Seattle. I would be very interested in hearing you speak on these subjects. Please add my name

to your postings.