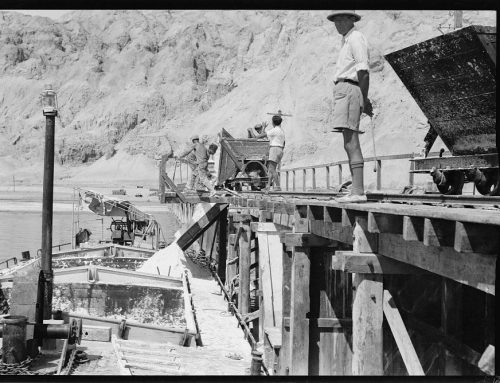

Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Jerusalem

By Berkay Gülen

I was on the bus number 25 from Tel Aviv University to the city center when I read on my phone that Israel had expelled the Turkish consul-general in Jerusalem on May 16, 2018. It was a day after the Turkish ambassador to Israel had been recalled for further consultations in Ankara and Turkey requested that Israel’s ambassador to Turkey temporarily leave the country as a protest against the deadly clash on the Israel-Gaza border.

I spent last spring in Israel in order to discuss Turkish-Israeli relations with Israeli foreign policy-makers. In terms of hearing first-hand analyses from foreign policy experts, it might have been the best time to arrive in Israel, but I had another struggle to deal with: How would I convince those high-profile experts to discuss strained Turkey-Israel relations that have been based on accusations, Twitter fights, and sometimes-deadly tension? Would my (Turkish) identity become an obstacle in building relationships of trust with the respondents? What if they did not find my questions about policy-making interesting enough and preferred to only speak about the turmoil of the last couple of days?

Interviewing in tough times

My research is on how foreign policy decisions are made when the bureaucratic elite and the political party in power have different expectations for policy, but have to work together. The changing relationship between the state bureaucracy and the party in power is the focal point of my research interests, and I discuss those issues by examining Turkish and Israeli foreign policies as case studies, and by using interviews as a source of data to understand the narrative of policy-makers.

Interviews are useful for understanding the perceptions of foreign policy-makers — diplomats, bureaucrats working for different state departments, and sometimes journalists, businesspeople, and academics — but there are not many studies focusing on Turkish-Israeli relations, and only a few of them use interviews to analyze decision-making mechanisms in those countries.

The new United States embassy in Jerusalem, opened in 2016

After interviewing policy-makers in Turkey for six months, I spent the first few weeks in Israel contacting potential interviewees with the help of my colleagues in Tel Aviv. First responses were encouraging and most of the potential interviewees seemed likely to share their perceptions. My concern about being a non-Israeli/non-Jewish researcher in Israel lessened when the respondents suggested that I contact their colleagues for further discussion. Sociological lexicon calls this method “snowball sampling,” but I prefer to call it, “why don’t you talk to my friend?” Usually contacting potential respondents via someone I had already talked to helped me to build a relationship of trust more efficiently.

In my second month in Israel, preliminary findings of my research were okay, although some of my interview requests were declined (though eventually, every researcher has to learn to live with this reality). On the morning of May 16, I was thinking about how to organize the interview notes and about sending last requests to the inboxes of potential respondents, when Israel expelled the Turkish general-consul in Jerusalem. The veteran Turkish diplomat, who also represents Turkey to the West Bank and Gaza, was requested to leave Israel following a short visit to the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Israeli Ministry used the same phrases Turkey had used when requesting that Israel’s ambassador to Turkey leave the country a day earlier, on May 15.

Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Jerusalem

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had recently exchanged furious words on Twitter regarding the opening of the US embassy in Jerusalem, and the duel over expelling diplomats was not a good sign regarding Turkey and Israel’s relations. The diplomatic relations had been cut off between 2010 and 2016, and the ambassadors had only recently been appointed following the reconciliation agreement in 2016.

Moreover, I aim to refrain from discussing current political developments in my research, and to focus instead on in-depth questions about how the foreign policy elite made its decisions between 1991 and 2014. My main concern at the time was to finish my appointments with the last respondents and navigate through current political debates.

A great colleague that I worked with at that time in Tel Aviv encouraged me to continue contacting possible respondents. She suggested that I focus on my own research questions and politely refrain from asking detailed questions about the last couple of days. I am still not sure how many respondents declined my request due to the developments in bilateral relations on those days, but, contrary to my expectations, most of the interviewees that I met after May 16 told me that in-depth questions on Turkey-Israel relations were timely and crucial. Though some of them preferred to discuss only recent events and did not comment on issues beyond the latest news, they still open-heartedly shared what they thought. All these experiences taught me that surprises are always on the way while researching.

Why interviews matter

Nowadays, diplomacy and international crises are being discussed on Twitter, and non-career foreign policy elites are preferred in the hope that they might find fast, efficient, miraculous solutions to multi-lateral problems. My research experience has taught me that, while diplomacy does need to change and embrace more pluralist discourse, career diplomats and bureaucrats are still valuable in adopting more nuanced approaches that go beyond the angry, daily, and usually very masculine-coded battle of words.

Four months have passed since I left Israel, and the diplomatic instability still goes on between Turkey and Israel, although there are rumors that both sides are willing to return to normal ties.

I still think that human interactions are vital in understanding and analyzing policy-making in the Middle East, especially when the academic literature on foreign policy analysis tends to understand actors through their attributed roles alone. Interviewing the political elite has taught me how to approach political concepts academically and ethically, without judging highly politicized perspectives.

Though policy-makers are subject to the heated political climate of a turbulent world, my experience suggests that they are more eager to discuss arguments and hear alternative approaches than we might think.

Leave A Comment