By Jennifer Hunter

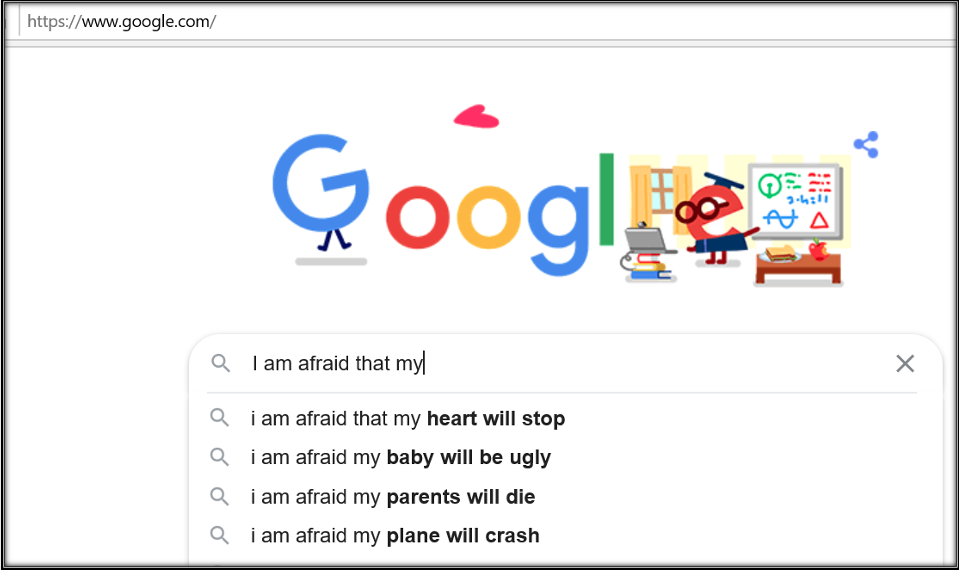

Google knows people’s deepest fears, and apparently one of them is “ugly” babies.

I first discovered this when on Google’s homepage I entered the search terms “I am afraid that my…” That is as far as I got before Google generated a list of popular suggested search terms. Second from the top, after “I am afraid that my heart will stop” was “I am afraid that my baby will be ugly.”

If Google search has any kernel of truth to it, people are more afraid of having an ugly baby than of their parents dying or their plane crashing. Bethany Ramos, an author for Mommyish.com, seems to confirm this with her blog post titled “On The Inside, We Are All Afraid Of Having An Ugly Baby.”

Why do people fear having an “ugly” baby? Certainly, we can place a great deal of blame on America’s far-reaching, yet unattainable, beauty standards, which seem to extend even to developing infants in the womb. Yet, historical studies of ancient sources reveal that while ancient people may not have shared our culturally constructed standards of beauty, anxiety over a baby’s looks is not a new phenomenon. Jews, Christians, and other inhabitants of the Greco-Roman world all shared anxieties over the appearance of their yet unborn children.

Ancient theories of vision & fears around conception

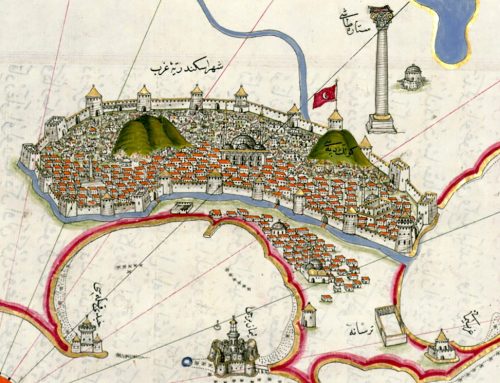

While modern parents may worry about the role of genetics, in the ancient world, beginning as early as the 5th century BCE, nothing posed a greater risk to a child’s appearance than what the expectant parents saw in the moments before or during the act of conception. Vision was viewed as a powerful tool in the reproductive process because of ancient scientific theories of sight. Ancient peoples in the Mediterranean — including Greece and Turkey, and the Near East, the region spanning from northeastern Africa to western Asia — understood sight as a natural, active force that had the power to impact both the viewer and the object being viewed.

Rachel Rafael Neis, associate professor in history and Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan and author of “The Sense of Sight in Rabbinic Culture,” explains that these theories of vision were not limited to the philosophical or medical elites, but that they prevailed across late-antique society (from roughly 200 CE to 700 CE), including among Greek scholars, rabbis, and Christian thinkers.

Bust from the Acropolis in Athens, Greece

According to ancient theories of vision, sight was a two-way street, in which the image that a person saw traveled along the optic nerve and imprinted itself upon the soul. Vision took on extra significance during sexual intercourse, when an imprintable soul was being embodied in a mothers’ womb. The ancients believed that expectant parents could influence the looks of their child by controlling what they saw with their eyes, or visualized in their minds, shortly before and during the moment of conception.

Empedocles, a fifth century BCE Greek philosopher, appears to have been the first to suggest that even an image in the imagination of a woman, spurred by the earlier sight of an actual material object, could affect the formation of her embryo. As a proof of this phenomenon, he recounts stories of women whose children resembled statues that they had fallen in love with, whose images were still in their minds when they conceived children with their husbands.

Sex and sight in the Talmud (and beyond)

A thousand years later, a similar consequence of sight and its lingering impact in the imagination can be seen in a number of conception stories in the Babylonian Talmud. These traditions seem preoccupied with controlling sight, both what women see and what men see, prior to sexual relations.

Illustration by J. Chapman, 1821.

The most well-known of these stories is associated with Rabbi Yohanan (b. Baba Metsia 84a):

Rabbi Yohanan used to go and sit at the gate of the ritual bath. He said, “When the daughters of Israel come out from the bath, they will look at me in order that they will have children as beautiful as I am.”

In this Talmudic story, the rabbis portray the sage Yohanan as inserting himself into the reproductive process of creating beautiful, pious Jewish babies. The two-way power of vision means that the lingering mental image of handsome Rabbi Yohanan will have a very real impact on the physical appearance of these Jewish women’s yet- to-be-conceived children, who will not be born ugly, but beautiful, like Rabbi Yohanan. What the daughters of Israel would have thought about R. Yohanan’s self-positioning is left untold.

The conception story of the children of Imma Shalom and her husband Rabbi Eliezer serves as another example of the impact that sight and mental images could have on the perceived quality of a child’s appearance. In Nedarim 20a-b, the rabbis ask Imma Shalom why her children are exceptionally beautiful:

She replied: “He converses [a euphemism for intercourse] with me neither at the beginning nor at the end of the night, but at midnight; and when he ‘converses’ he uncovers a handbreath and covers a handbreath and he resembles one driven by a demon. And when I asked him why [he behaves this way] he answered, ‘So that I may not set my eyes on another woman and my children come to be like bastards.’” (As translated in Neis, p. 132)

In this story, Rabbi Eliezer keeps his sight pure by avoiding looking at his wife’s body, preserving her modesty, and tries to complete coitus as quickly as possible (“as if driven by a demon”). This in turn keeps his imagination pure, by preventing his mind from producing images of other women, inadvertently leading to adultery. The beauty of his children give witness to the purity of his image-producing mind.

The rabbis worried not only that lingering mental images of men could negatively impact a child’s appearance, but also those of women. The following story seems to betray the male rabbis’ fears that they cannot control the gaze of their wives. In Genesis Rabbah 26:7, Rabbi Berekhayah recounts the following story:

A woman would go out into the marketplace, and she would see a young man and lust after him. She would go and have intercourse and bring forth a young man resembling him. (As translated in Neis, p. 155)

After returning home, the woman has sexual intercourse, presumably with her husband, but instead of resembling her husband in appearance, the resulting child resembles the handsome young man she saw in the marketplace, whose image was still lingering in her imagination at the time of her child’s conception.

For the rabbis, seeing was dangerous and had real implications in the creation of progeny, whether that impact be that one’s children were ugly, beautiful, or did not resemble their parents.

A similar concern seems to be behind a passage in the Gospel of Philip, which is a non-canonical Christian text that belongs to a set of manuscripts known as the Nag Hammadi collection:

The children a woman bears resemble the man who loves her. If her husband loves her, then they resemble her husband. If it is an adulterer, then they resemble the adulterer. Frequently, if a woman sleeps with her husband out of necessity, while her heart is with the adulterer with whom she usually has intercourse, the child she will bear is born resembling the adulterer.

Like the woman in Genesis Rabbah, the Gospel of Philip expresses a similar angst that a woman’s child may not bear the appearance of his father if the woman’s thoughts are filled with mental images of another man.

Overcoming anxieties around appearance, past and present

While they may have pinned the source of the problem on vision rather than genetics, the attempts of ancient Jews and Christians to control the gaze of married men, and especially women, demonstrate that, like Googlers today, ancient people worried about having a baby whose appearance fell short of the ideal.

Maybe what these traditions show is that fear about ugly babies is really just fear that babies won’t look like us; that we won’t be able to love our babies as our own … or that we will have no control over our babies’ health.

Whatever the reason, maybe it is time that we set aside this ancient anxiety. Let’s stop worrying about ugly babies, and instead think about the detrimental societal effects that this obsession with appearance has on our children. If we work to conquer this anxiety in ourselves, we will be better able to raise our children to have healthy conceptions of their own bodies, and the bodies of others.

Jennifer Hunter is a Ph.D. student in the interdisciplinary Near and Middle Eastern Studies Program. She earned her B.A. with a double major in religious studies and modern languages (Spanish and German) from Northern Arizona University. After earning her undergraduate degree, she attended Harvard University Divinity School, where she earned a Master of Theological Studies with a cross-comparative focus on religions in Late Antiquity (2nd-8th centuries CE). Post-master’s, Jennifer made her way back to Northern Arizona University, where she served as a lecturer in religious studies in the Comparative Cultural Studies Department for five years. Her commitment to the comparative study of religion is what drew her to the UW, and her current research interests focus on the study of ritual among Jews, Christians, and other religious groups of the ancient Near East, especially domestic rituals of the home that help shed light on the role of women in religious life.

Jennifer Hunter is a Ph.D. student in the interdisciplinary Near and Middle Eastern Studies Program. She earned her B.A. with a double major in religious studies and modern languages (Spanish and German) from Northern Arizona University. After earning her undergraduate degree, she attended Harvard University Divinity School, where she earned a Master of Theological Studies with a cross-comparative focus on religions in Late Antiquity (2nd-8th centuries CE). Post-master’s, Jennifer made her way back to Northern Arizona University, where she served as a lecturer in religious studies in the Comparative Cultural Studies Department for five years. Her commitment to the comparative study of religion is what drew her to the UW, and her current research interests focus on the study of ritual among Jews, Christians, and other religious groups of the ancient Near East, especially domestic rituals of the home that help shed light on the role of women in religious life.

Leave A Comment