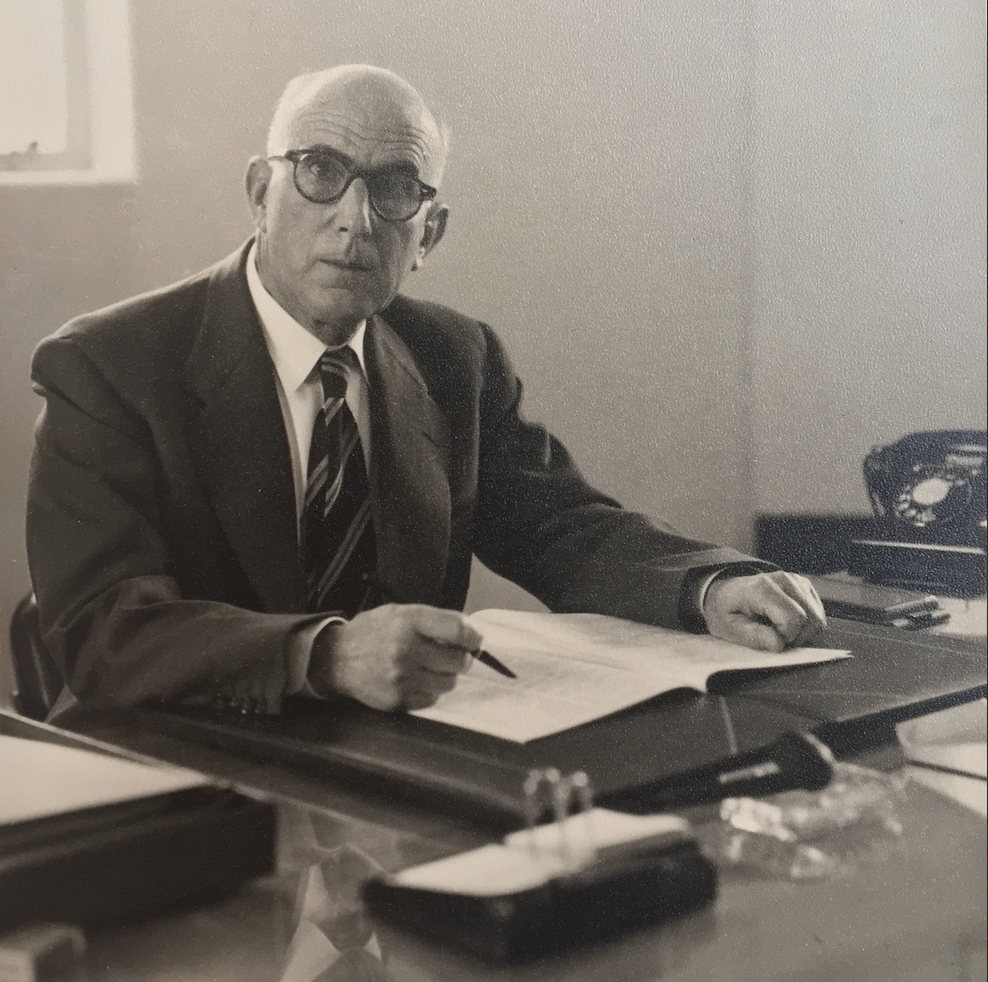

Haim Galante (1890-1980) at his desk. Galante was born in Bodrum, Turkey. After immigrating to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in the early twentieth century, he built an import-export business. Photo from the author’s private collection.

By Hannah S. Pressman

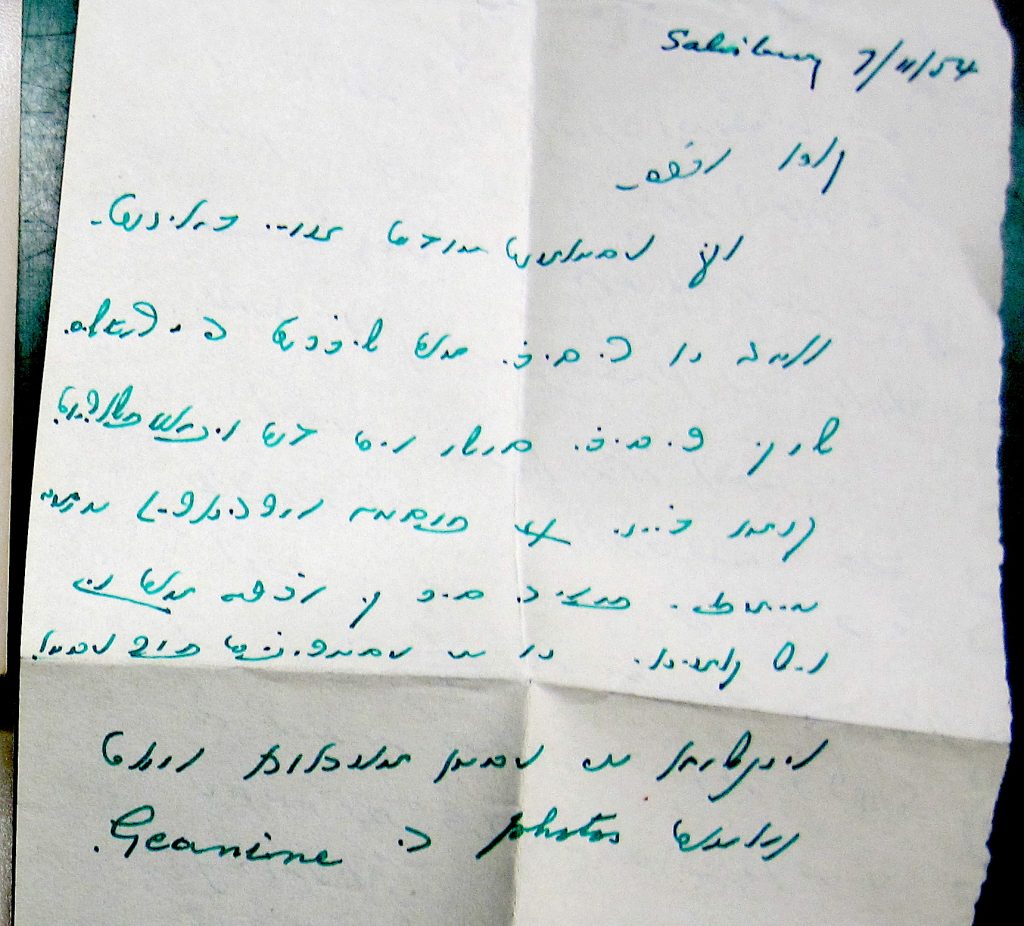

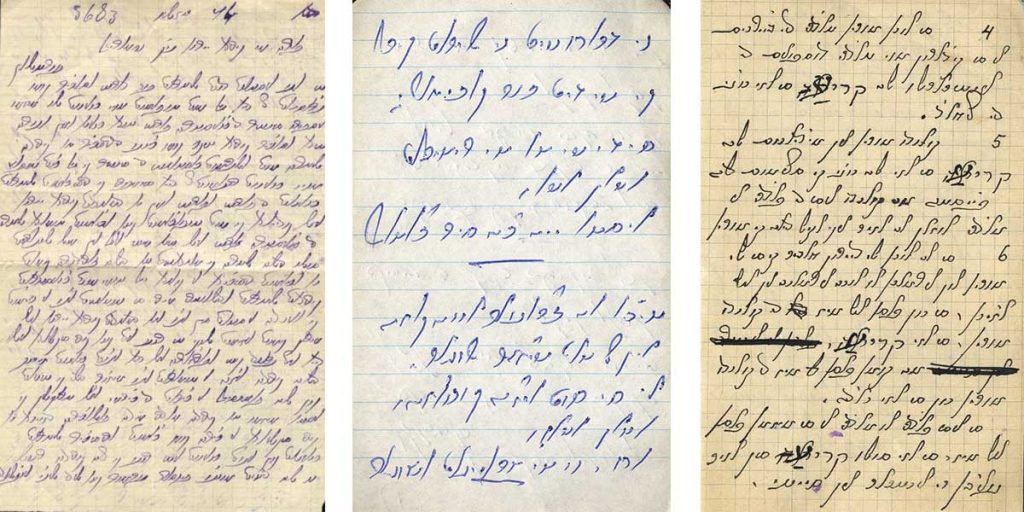

The letter in front of me was dated 1954 and appeared to be written in Yiddish or Hebrew. However, when I looked more closely at the neatly inked sentences, I could tell this was not the case: nearly all the letters looked like lines — shorter lines and longer lines, lines that turned and swooped beneath words, as if bearing whole streams of thought along with them. There were also occasional waves and loops that curlicued off the ends of words, adding a springy sense of playfulness to the text.

Portion of the letter from Haim Galante to his brother, Abraham. (ARC. Ms. Var. 411 Abraham Galanté Collection, Archives Department, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem.)

I couldn’t assimilate the appearance of this script to my knowledge of reading other Jewish languages; I had learned Hebrew as a child and studied it intensively in graduate school, where I also acquired Yiddish. The insistent parade of lines and ligatures on the page before me did not magically coalesce into the Ladino (or Judeo-Spanish) that I had been studying since the start of the pandemic. The only words I could read easily were the ones that the author had penned in English: Jeanine and Linda, Lilian and Hilda. While the letter’s contents were mysterious, these names were not; they belong to women on the Sephardic side of my family, who came from the island of Rhodes.

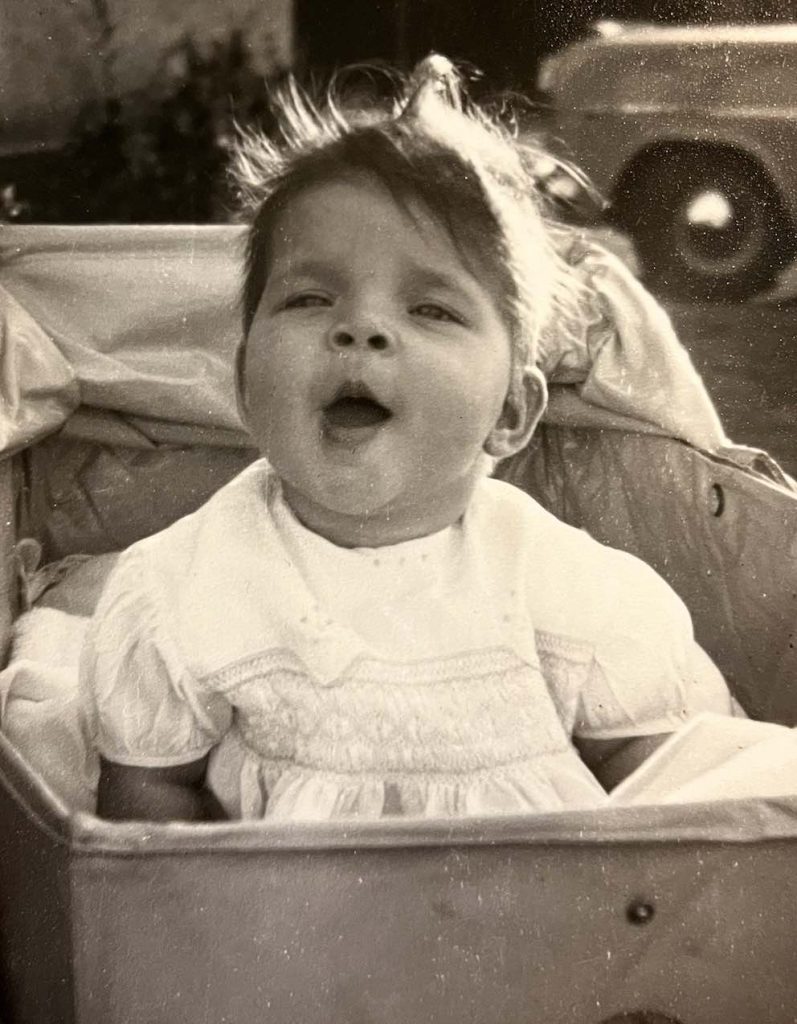

Besides these names, I had one other clue urging me to translate the letter: three photographs of a baby, her hair backlit by the sun. I had seen these pictures before — they felt as familiar as the handwriting felt unfamiliar. Yes, I whispered to myself, half crying and half laughing: these were pictures of my mother.

What is soletreo?

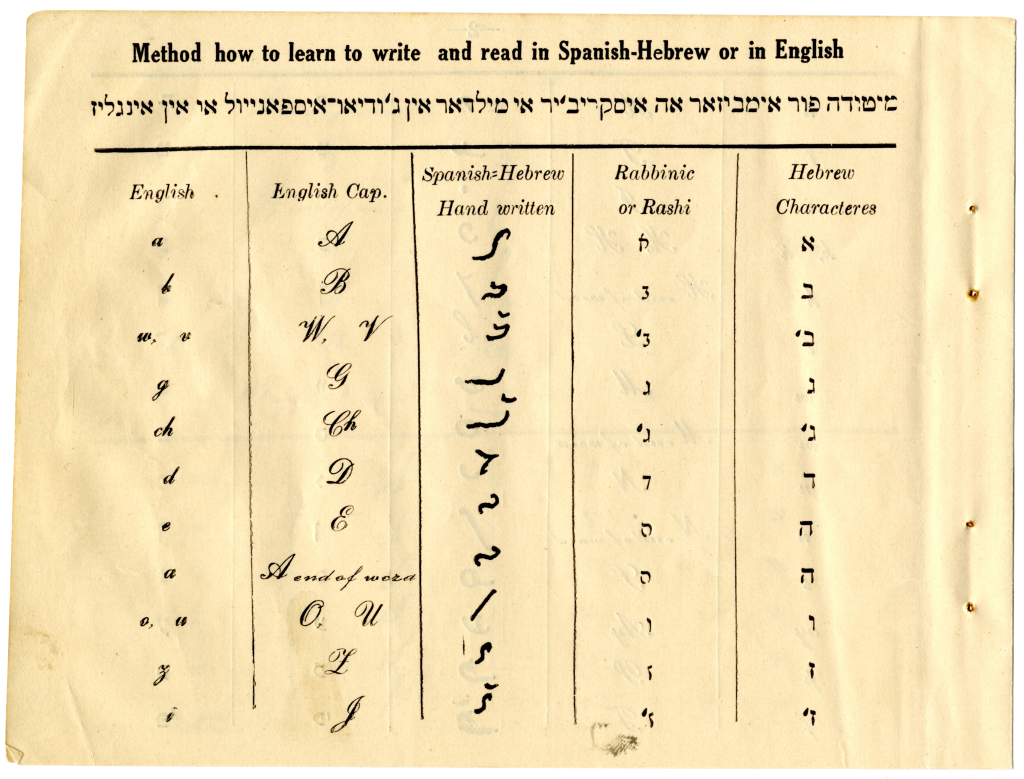

Soletreo (also spelled solitreo) is a cursive script based on Hebrew letters, and its very name carries the Iberian-based history of the Ladino language. Soletreo comes from the Portuguese verb soletrar, meaning “to spell, to compose a word.” Embedded within soletrar is the word letra, from the Latin littera, which means “a letter of the alphabet.” These are the letters that Sepharadim have used to communicate and compose, in sacred and secular contexts, for hundreds of years since their dispersal from the Iberian Peninsula, primarily in the lands of the Ottoman Empire.

Page from “Livro de Embezar las linguas Ingleza i Yudish,” a guidebook for Sephardic immigrants, with side-by-side comparison of the “Spanish-Hebrew” alphabet (soletreo), standard Hebrew alphabets (rashi and block type), and the Latin alphabet (ST0007, courtesy Isaac Azose).

On his Documenting Judeo-Spanish website, Bryan Kirschen, Associate Professor of Spanish and Linguistics at Binghamton University, calls soletreo “[a] nearly-extinct alphabet to an endangered language.” I’ve been aware of soletreo’s precarious existence since Professor David Bunis‘ revelatory 2013 lecture on “Ladino / Judezmo as a Jewish Language” at the UW (profiled here). As an intermediate-level student who had been studying Ladino online for only a year, was I even ready to be initiated into the very small club (estimated at about one hundred people globally) who can decipher this vanishing script? What, I imagined someone inquiring, was the point of learning to write an alphabet that almost nobody could read?

The beginnings — and challenges — of a soletreo journey

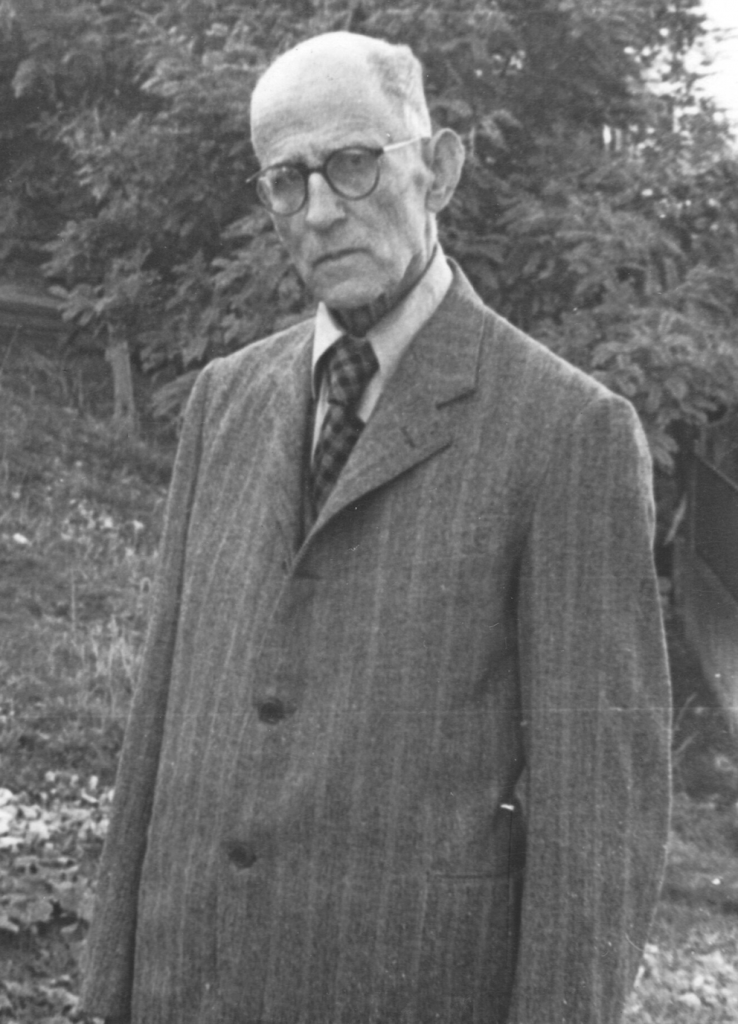

Abraham Galante (1873-1961) was a Sephardic intellectual who played many roles in the Turkish Jewish community, academia, and national politics. Photo from the author’s private collection.

Receiving a copy of the letter last June was a strange twist of fate: had I not contributed a chapter to “Sephardic Trajectories,” the subject of UW’s 2021 Ladino Day program, I might never have learned of this letter acquired by the volume’s co-editor, Kerem Tınaz, an Assistant Professor of History at Koç University. And had Abraham Galante not been a significant enough figure to warrant his own archive in the National Library of Israel, it is very possible that the letter from his younger brother Haim would not have been preserved. As soon as I saw the oval stamp on the back of the envelope, “H. Galante—Salisbury,” a mark I had seen on other documents mailed from my great-grandfather’s import-export business in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), I knew that I had to understand what was inside.

However, trying to read Ladino in cursive script posed a new kind of challenge, even for someone like me with experience translating a variety of Hebrew-based texts. Depending on the writer, some soletreo letters differ in appearance by the most minuscule of degrees, which makes it hard for a beginning reader to decipher and gain confidence. The letters, also known as ganchos — Spanish for “hooks” — really do appear similar to the untrained eye.

There are also confusing instances wherein soletreo letters look like certain Ashkenazi cursive Hebrew letters, but don’t represent the same sounds (here’s looking at you, final mem and samekh!). Additionally, soletreo letters are based on Rashi script. While once taught in Jewish elementary schools (the meldar or Talmud Tora) in communities throughout the former Ottoman Empire, today’s Ladino language courses typically utilize the phonetic system that spells words with Latin characters. For this, most teachers rely on the spelling conventions outlined by Moshe Shaul in “Aki Yerushalayim,” a Ladino cultural magazine published in Israel.

Kirschen’s soletreo class, offered last winter, helped me to accept soletreo on its own terms and expand my skill-set each week. To my delight, I began to be able to read parts of the archival documents that he provided. Having a basic Ladino vocabulary proved advantageous; complete fluency was not, as I had supposed, a prerequisite for soletreo study. From a confusing cluster of ganchos, soletreo gradually became a language of reading, writing, and understanding another world — one nonetheless connected to my own.

Soletreo documents penned around the world evidence varied handwriting styles. L to R: A dictated letter sent from the Capelouto family in Rhodes to their relatives in Seattle, dated December 4, 1922 (ST01030-10, courtesy Al Shemarya); soletreo notes by Salonican-born journalist and educator Albert D. Levy (ST00682, courtesy Linda Tacher Robke); a page from Reverend Samuel Benaroya’s notebook (ST00272, courtesy Judy Amiel). Benaroya was born in Edirne (Adrianople).

How soletreo can help decode the past

Now I have another way to access many genres of Ladino literature, from the intimate to the official, which lie in collections waiting to be discovered and which can only be read in their original script. Now I can decode the names scribbled on the inside cover of my great-granduncle B.S. Leon’s mahzor (prayer book) which he took with him to worship at the Sha’are Shalom synagogue in Salisbury (now Harare).

A common language helped far-flung Sephardic communities stay connected to each other and to the past. For scholars in the fields of Sephardic, Ottoman, and Jewish history, acquiring soletreo is key to understanding how Sepharadim have communicated with each other and recorded their own stories. At the same time, soletreo is part of the global history of Jewish writers who took Hebrew’s alphabetic building blocks and created something distinctive based on their regional vernaculars. The danger of calling soletreo a lost art, therefore, is that we risk also losing all of the precious layers of history that are wrapped up in this script.

The author’s mother as a baby. This photograph matches one of three pictures sent by Haim Galante to his brother, Abraham. From the author’s private family collection.

It took several weeks of painstaking work, but I succeeded in decoding my great-grandfather’s soletreo letter and developing a translation to show my family. Haim was certainly the quieter Galante brother — he didn’t lecture at Istanbul University or serve in the Turkish parliament, as Abraham did — but nevertheless he has taught me a lot. Through his evocative descriptions of his daughters and granddaughters, Haim gave me a new perspective on my family’s time in Rhodesia, the place they chose to live when the Ottoman Empire crumbled. The letter shows a proud Grandpapa sharing haberes buenos, good news, with his famous far-away brother.

I imagine Haim inking the final letras in his soletreo letter, using the centuries-old system that our Sephardic ancestors devised to represent muestro spanyol (“our Spanish”). I see him tucking the adorable photographs of my mother next to his note. I watch as the letter arrives in the stone house on Kınalı, the island off the Turkish coast where Abraham Galante lived during his later years. I witness Abraham pulling out the note, the photographs falling onto the table, lighting up his tired eyes in their round spectacles. His new grand-niece in Africa.

Hannah S. Pressman is the Director of Education and Engagement at The Jewish Language Project, and writes about modern Jewish culture, religion, and identity. She earned her Ph.D. in modern Hebrew literature from New York University and has published her work in a broad range of academic and journalistic venues. Recent publications include contributions to What We Talk About When We Talk About Hebrew (and What It Means to Americans) (University of Washington Press, 2018); The New Jewish Canon: Ideas & Debates, 1980-2015 (Academic Studies Press, 2020); and Sephardic Trajectories: Archives, Objects, and the Ottoman Jewish Past in the United States (Koç University Press/University of Chicago Press, 2021). She is currently at work on “Galante’s Daughter: A Sephardic Family Journey,” a multi-vocal memoir that traces her family’s twentieth century travels from the Levant and Lithuania into southern Africa and beyond. This project was recently recognized with a Research Award from the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute. Pressman is the former Communications Director, Graduate Fellowship Coordinator, and Hazel D. Cole Fellow at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies.

Hannah S. Pressman is the Director of Education and Engagement at The Jewish Language Project, and writes about modern Jewish culture, religion, and identity. She earned her Ph.D. in modern Hebrew literature from New York University and has published her work in a broad range of academic and journalistic venues. Recent publications include contributions to What We Talk About When We Talk About Hebrew (and What It Means to Americans) (University of Washington Press, 2018); The New Jewish Canon: Ideas & Debates, 1980-2015 (Academic Studies Press, 2020); and Sephardic Trajectories: Archives, Objects, and the Ottoman Jewish Past in the United States (Koç University Press/University of Chicago Press, 2021). She is currently at work on “Galante’s Daughter: A Sephardic Family Journey,” a multi-vocal memoir that traces her family’s twentieth century travels from the Levant and Lithuania into southern Africa and beyond. This project was recently recognized with a Research Award from the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute. Pressman is the former Communications Director, Graduate Fellowship Coordinator, and Hazel D. Cole Fellow at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies.

Bendichos Munchos para byen!