Logo for the 7th annual ucLADINO Symposium

By Molly FitzMorris

How can it be that Ladino is both old and new? The 7th annual ucLADINO Symposium, hosted at the University of California, Los Angeles this year, explored that very question.

The only annual Ladino-specific conference in the United States, the Symposium was first held in 2012, organized by then-UCLA graduate student Bryan Kirschen. (You may have met Dr. Kirschen, now an Assistant Professor at SUNY Binghamton, during his recent 6-week visit to Seattle.)

Since its establishment, the ucLADINO Symposium has become a well-known gathering place for scholars and community members alike. In previous years, Seattleite Albert Maimon, Stroum Center Graduate Fellow Emily Thompson, and I have given presentations, and Professor Devin Naar, Chair of the Stroum Center’s Sephardic Studies Program, delivered a keynote lecture in 2016.

This year’s theme was “New Directions, Old Roots,” which I believe to be both a pithy summation of the development of Ladino and an apt description of approaches to Ladino scholarship and awareness in the 21st century.

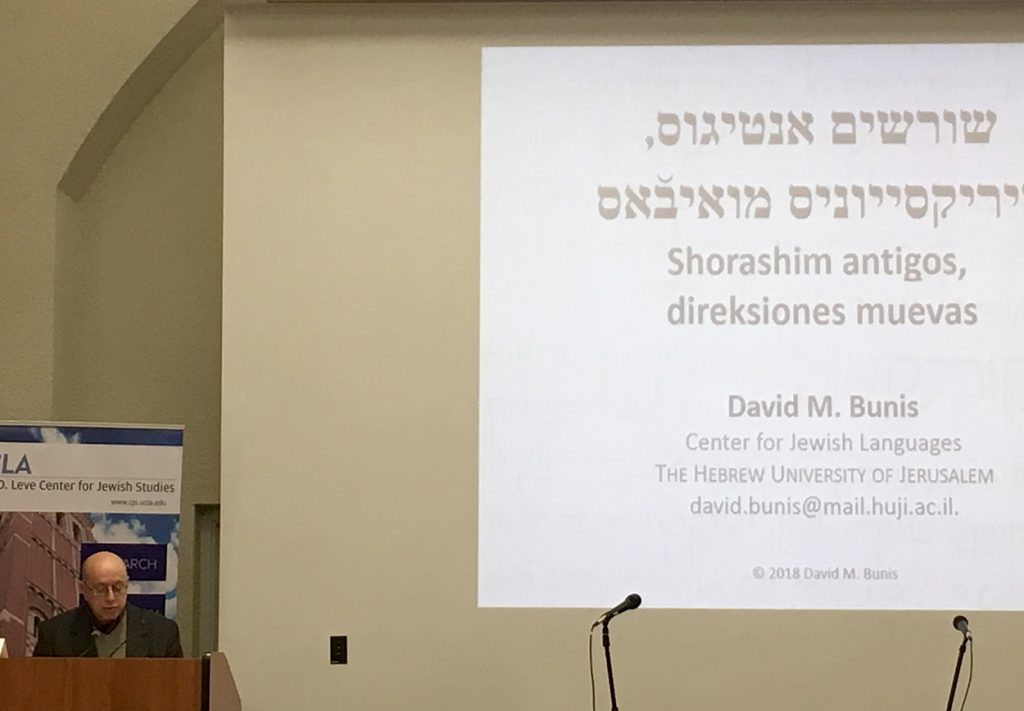

Prof. David Bunis presents his keynote talk “Shorashim antigos, direksiones muevas” (“Old roots, new directions”)

In his opening keynote lecture, Professor David M. Bunis of Hebrew University in Jerusalem — who taught Ladino classes at the University of Washington in 2013-2014 — introduced the “old roots, new directions” theme of the conference, outlining a history of the development of the Ladino language.

As Professor Bunis described in his talk, the very essence of Ladino is, in fact, the “new-old fusions” of Spanish (old) and the languages the Jews encountered in the diaspora (new). These new-old fusions are precisely what I love about Ladino and why I find the language so interesting to study. (You may have seen my recent talk at the Stroum Center’s Graduate Fellow Research Presentations, where I discussed one such fusion, the use of non-Turkish roots with the Turkish suffix -dji to create new words like shinedji ‘shoeshine’.)

Statue of Mafalda in Buenos Aires, Argentina

The old-new fusion was also manifest in other academic presentations, which explored new and exciting approaches to the study of Ladino history and traditions. One panel explored Ángel Pulido’s Españoles sin patria, French Sephardic linguist Emile Benveniste and his work with Ladino, and the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language’s establishment of a Ladino Academy. Another panel explored the Sephardic community and language of the Habsburg Empire, Turkish words used in Ladino, contact with Balkan languages, and the relationship between migration and Sephardic music. One talk even compared the Argentine comic strip character Mafalda with the traditional Sephardic character Djoha!

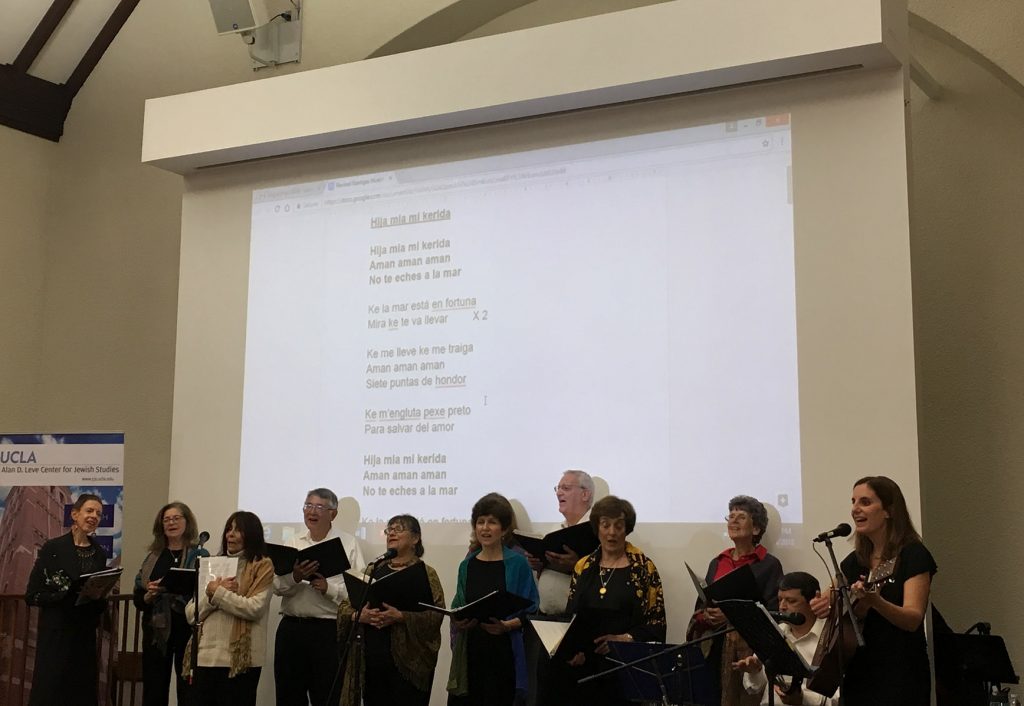

The Kantigas Muestras choral group performs “Hija mia mi kerida”

Representing the old traditions of the global Ladino speech community were two community panels. One such panel included a performance by a group called Kantigas Muestras. Kantigas Muestras (Ladino for “our folksongs”) is a Ladino singing group that meets twice a month in Los Angeles to sing together while also connecting with their heritage and promoting Sephardic culture and the Ladino language. They’re kind of like the Ladineros – Seattle’s Ladino-speaking group – of Los Angeles! Kantigas Muestras was started at the 2014 ucLADINO Symposium, when several community members began spontaneously singing together at the conference reception (a spectacular moment that I witnessed). They enjoyed it so much that they decided to meet regularly. The group performed some songs that I knew, like “A la una yo nasi,” and some that were new to me, like “Buena semana.”

The second community panel of the conference was called “Celebrating the Sephardic Heritage Cookbook.” This panel included five women who were heavily involved with the creation and publication of this cookbook, which was published in 2016 by Or Chadash Sisterhood of the Sephardic Temple Tifereth Israel of Los Angeles. Two members of the panel, Linda Capeloto Sendowski and Mireille Mathalon, lived in Seattle as children.

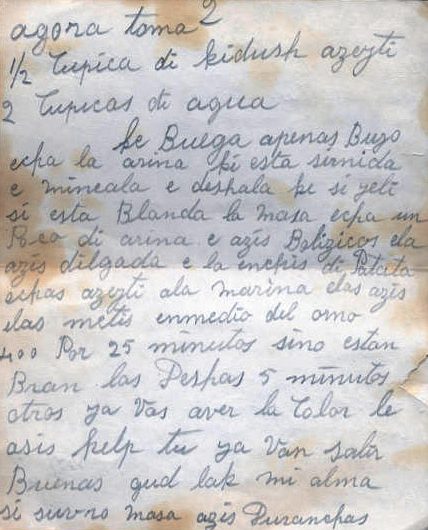

Rachel Shemarya’s “Borecas de patata” (potato borekas) recipe

The women noted that an important part of creating this cookbook was going to their mothers and grandmothers and determining standardized measurements for the recipes. If you’re not familiar with the sort of measurements used by twentieth century Sephardic women in many of their recipes, you can see examples (such as “1/2 cupica di kidush azeyti,” or 1/2 kiddush cup of oil) in Seattleite Rachel Shemarya’s borecas di patata recipe from the 1950s. Standardizing the measurements was important, according to the panel, because the goal of the publication of the cookbook was to make the recipes accessible to everyone, Sephardic Jewish or not.

The most important thing that I took away from this conference is hope for the future of the Ladino language and Ladino scholarship. So much important work, in both the old camp and the new camp, is being done to keep Ladino alive in the 21st century.

Carlos Yebra López of NYU and New York Ladino speaker Benni Aguado have created a YouTube channel called Ladino 21, where you can find videos of the two of them chatting, telling stories, and singing in Ladino. The ladies of the Sephardic Heritage Cookbook panel suggested that perhaps one day there could also be a YouTube channel featuring Sephardic cooking demonstrations in Ladino. The creation and publication of videos in Ladino is a crucial contribution to the documentation of the language.

I am also hopeful because people around the world are learning about and studying Ladino. This year’s program included presenters from as far away as Vienna, Sofia, and Tokyo! I am hopeful because undergraduate students are dabbling with Ladino and asking important questions about the formation and structure of the language. I am hopeful because many institutions, including UCLA, are establishing their own collections of Ladino and Sephardic artifacts, much like the Sephardic Studies Digital Library Collection in Seattle.

It is clear that Ladino research and documentation is moving forward into the future, while not forgetting the important history of the language and its speakers. Inspired, as I am each year that I attend this conference, I left this conference ready to continue my own investigation of new-old fusions in the Ladino language of Seattle.

Molly FitzMorris, Isaac Alhadeff Sephardic Studies Fellow, is a third-year PhD student in the Department of Linguistics. She has a BA in Latin American Studies from New York University, and an MA in Hispanic Studies from the University of Washington. Her research focuses on the documentation of Ladino in Seattle, and her two current projects explore the dialects of Ladino spoken in Seattle and the use of a common Turkish suffix in Ladino. Molly helped organize the first three International Ladino Day celebrations in Seattle, and is an occasional student at the weekly Ladineros classes.

Molly FitzMorris, Isaac Alhadeff Sephardic Studies Fellow, is a third-year PhD student in the Department of Linguistics. She has a BA in Latin American Studies from New York University, and an MA in Hispanic Studies from the University of Washington. Her research focuses on the documentation of Ladino in Seattle, and her two current projects explore the dialects of Ladino spoken in Seattle and the use of a common Turkish suffix in Ladino. Molly helped organize the first three International Ladino Day celebrations in Seattle, and is an occasional student at the weekly Ladineros classes.

Further Reading

- Defining the Ladino Speech Community in Seattle by Molly FitzMorris (2015)

- Ladino from Seattle to Buenos Aires by Molly FitzMorris (2015)

- Why I’m Teaching a New Generation to Read and Write Ladino by David M. Bunis (2014)

Deke el artikolo es en la lingua eng]es??? Komo un peshkado mui chiko, io no so un grande professor de las universidades, penso ke ken kere eksplikar una konferensia a esta tema prime skrivir en la lingva LADINO. Sanos I rezios ke estas.

Buenas tadres, Sinyor Benatov. Komi dizi en Facebook, eskriki este artikolo para kompartir lo ke ambezi kon mis amigos en la komunita sefaradi en Sitali, munchos de los kualos no avlan la lingua ladino. Me plazeria muncho eskrivir artikolos en ladino para este sitio web, ama komo puedes ver, todo esta en ingles. Si kere el Dio, en el futuro, vamos a poder tener artikolos eskritos en ladino en este sitio web! Saludes desde Siatli!

Good afternoon, Mr. Benatov. As I said on Facebook, I wrote this article to share what I learned with my friends in the Sephardic community in Seattle, many of whom don’t speak the Ladino language. I would very much like to write articles in Ladino for this website, but, as you can see, everything is in English. Hopefully, in the future, we’ll be able to have articles written in Ladino on this website! Best wishes from Seattle!

Quiero terminar mi Ph. D. En la causas y efectos de lenguas maternas, incluyendo ladino en un mundo extraño a ellas. Todo lo relacionado con la lengua judeo ladino me conviene. Vivo en Nueva York, pero mis raíces son gallegas. Ahí incluyo transfundo etnico judio.