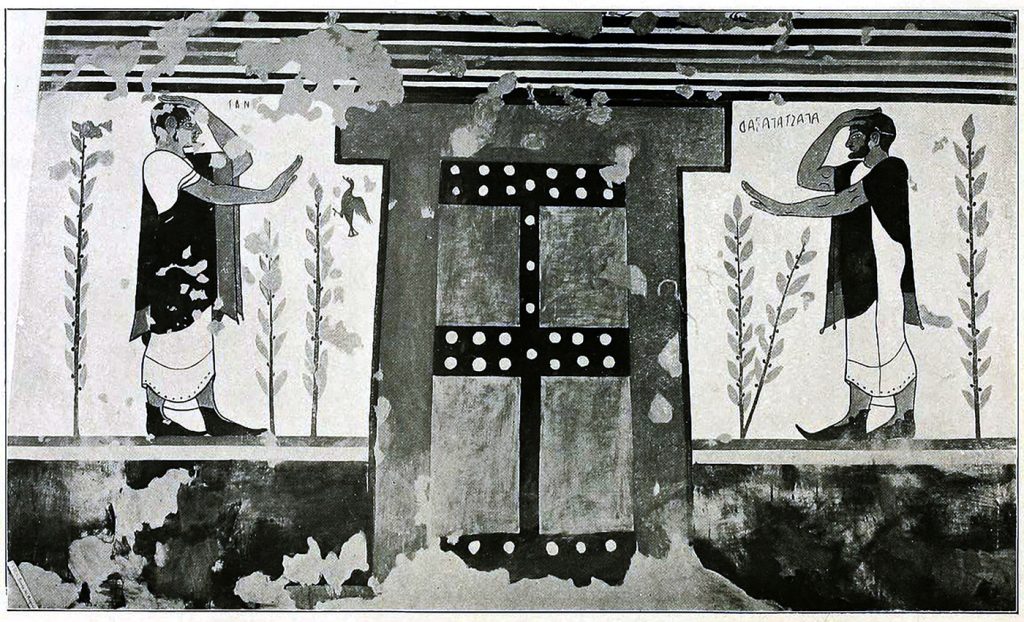

Etruscan tomb painting (located in modern-day Italy) depicting the divinatory practice of augury, the reading of birds’ behaviors for omens of the future. Via Wikimedia Commons.

By Forrest Martin

We’ve all seen videos of animals acting in ways that can only be described as derpy, like the bulky dog that really wants to swim. These are the ones that show up in our social media feeds most often.

On the other hand, I’m sure we’ve all seen viral videos of animals seeming to act in very sophisticated, even altruistic ways. For example, remember the dog that saved its friend from drowning in a pool. Or what about Vali, the Hungarian bear who rescues a drowning crow? Of course, I could go on with many other instances of seemingly selfless animals.

Yet the criteria that we use to think about morality and ethics remains firmly anthropocentric (centered around humans) in many ways, especially in the academy. If animals are not cognitively aware, and their actions are not motivated by a conscious emotion or even consent, moral philosophers often dismiss animals as moral agents. Morality is conceived as an expression of rationality.

Yet personally, my intuition tells me that there is more to the story. Indeed, any dog owner knows that dogs really are all “good boys” (or girls) — sorry, cat lovers. These intuitions and the appearance of moral behavior prompt Welsh philosopher Mark Rowlands to take a more favorable view toward animals as moral subjects.

This anthropocentrism is something that we share with most ancient peoples, but for different reasons. They weren’t so obsessed with cognition as a measuring stick for morality — for they viewed behavior as even more vital than internal thoughts and motivations. They indeed often saw humans as the centerpiece of the ordered universe — but not the only moral actors on nature’s stage.

Some ancient Israelite texts portray animals as knowledgeable of the divine and obedient to the divine will. I have chosen to focus on birds in particular in these texts because they (along with fish and insects) are the animals to which we moderns are most reticent to grant moral agency, cognition, and personhood. Let me begin by offering some ancient Near Eastern context for thinking about ancient perceptions of birds.

Why birds?

Across the ancient Near East, birds were among the animals most laden with cosmological significance. In Egypt, several birds were strongly associated with divinities, including falcons, ibises, vultures, and more.

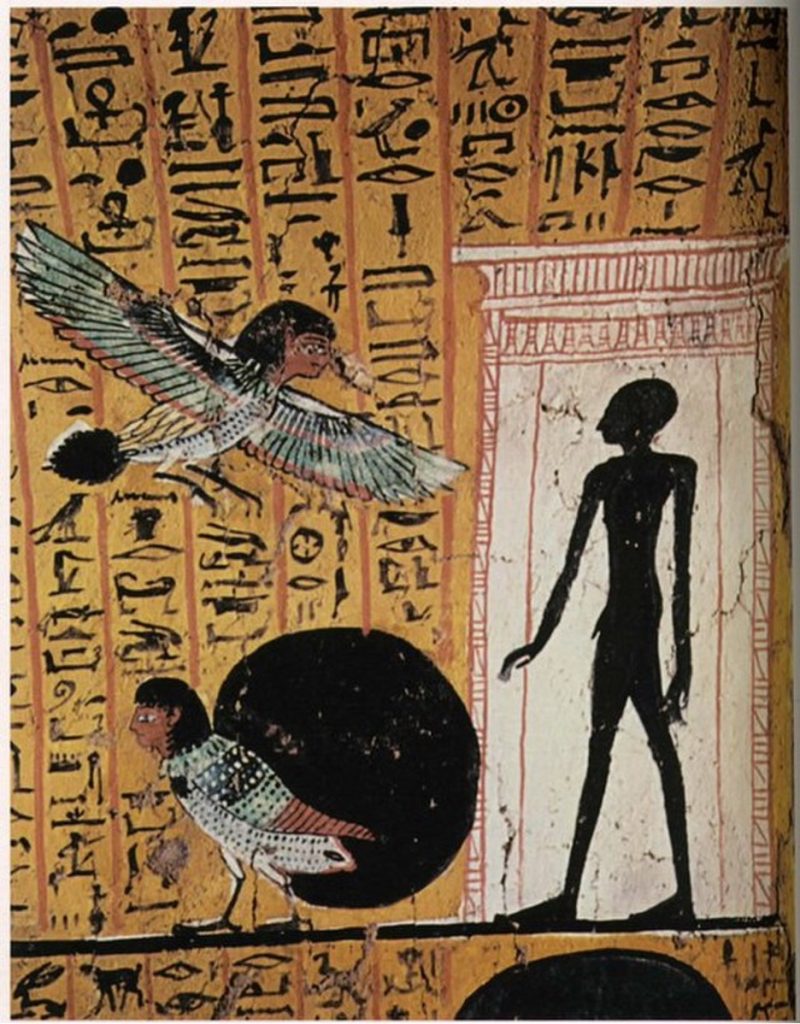

Egyptian tomb painting depicting two ba-birds. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Additionally, the ancients often associated the departed with birds. Egyptians represented one component of the human being, called the ba (often translated as “soul,” or “personality”), in art as a human-headed bird. Ancient Mesopotamian literature makes a similar connection; in the Descent of Ishtar, the dead are described as “clothed like birds in garments of feather” (l. 10).

To add to the significance of birds’ relation to the divine in the ancient world, I should mention the practice of augury, or flight-pattern divination. This is a practice that is most closely associated with the ancient Mediterranean in modern times (though it did not originate there). Those interested in Greek epic may recall that at the end of the Iliad, Trojan King Priam asks for a “bird sign” from Zeus before going out to meet his son’s killer:

Father Zeus… send a bird of omen, the swift messenger that to yourself is dearest of birds and is mightiest in strength; let him appear on my right hand, so that noting the sign with my own eyes, I may have trust in it (Il. 24.308-313, trans. Murray).

Having established a few associations between birds and divinity, let’s explore a few passages from the Hebrew Bible that display a similar association.

Birds and the divine in the Hebrew Bible

Israel’s god is also closely related with animals in the Hebrew Bible, often by an author’s usage of animal imagery in reference the deity. In the Hebrew Bible, the only animals that Israel’s god is connected with are the wild auroch (a now-extinct relative of cows; see Deut 33:17), the lion (see Amos 1:2); and, in line with their divine connotations in the ancient Near East, birds (see Deut 32:10-12).

Notably, these are all wild animals. It would be disturbing to ancient people to see the deity in a domesticated animal under human control, which is contrary to the nature of divinity.

Sometimes, Israelite authors convey the LORD’s parental characteristics using avian imagery: “By his pinion he will shut you in, and under his wings you will take refuge. A shield and a fortress wall are his faithfulness” (Ps 91:4).

Biblical authors sometimes call their readers to attend to the behavior of birds, which suggests a deeper knowledge on the part of the animals:

6 All [of those people] turn to their ways of running,

like a horse plunging into battle.

7 Even the stork in heaven knows its appointed time,

and the turtledove, and the swallow, and the song bird,

they keep the time of their arrival.

But my people do not know the LORD’s justice (mišpaṭ).

8 How can you say, ‘We are wise and the LORD’s Torah is with us’?

Look, surely the scribes’ stylus of lies has made it a lie (Jer 8:6b-8).

Identifying animal terms used in the Bible with our own classification system can be tenuous at times. The stork is the most surely pinpointed among the four species listed — it is likely the white stork which migrates from Africa to Europe by way of the Levant.

The white stork that migrates through the Levant. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The horse and the birds get very different treatments by the prophet Jeremiah in this passage. Let’s begin with the birds. They know (ydꜤ) the times, and keep (šmr) their arrival times. Medieval commentator Qimḥi (RaDaQ) noted that these birds “have knowledge regarding how to move away from harm and move toward goodness.” They do what humanity fails to do in the surrounding context: to know the divine will and act accordingly in obedience.

The point of the passage culminates at the end of v. 7: “My people do not know the mišpaṭ of the LORD.” The term used, mišpaṭ, often translated as “justice,” carries a judicial and ethical connotation. The direct contrasts suggests that the birds do know it. Thus, Jeremiah here articulates clearly that birds have knowledge of God and God’s will. Therefore, I suggest that Jeremiah portrays the migrating birds as knowing God and knowing what is just.

Not so for the horse. Humanity is likened to the horse in battle — it rushes headfirst into war, bringing harm to itself and others in the process. Only tamed horses act in such a way — that is, only through human interference do horses abandon their instinct and act in this way.

Animals’ divine knowledge in the book of Job

Similarly, in the biblical book of Job, in one of his speeches to his so-called “friends,” Job invites them to consider the inherent knowledge of animals:

7 “But ask the animals, and they will instruct you,

and the birds of the heaven, and they will inform you;

8 or ask the land, and it will teach you,

and the fish of the sea will declare to you.

9 Who among all of these does not know

that the LORD’s hand has done this?

Here, Job points out that his interlocutors cannot perceive God’s actions, whereas the fact would be apparent to any animal. The construction makes use of the tripartite structure of the world — heavens, earth, and sea, by way of their inhabitants — to make reference to all wild animals. Ask any animal at all, from the heights of the sky to the depths of the sea, and they will confirm that they discern the LORD’s action.

Learning from animals

In summary, in ancient Israel, birds were thought to know things, and they acted rightly before the LORD. This relates to the perceived relationship between birds and the divine in multiple ancient Near Eastern cultures. This is why they were worth observing, and even worthy of tutelage as not only moral subjects, as some modern philosophers have argued, but also exemplars.

We can learn from ancient Israel and its neighbors to regain a little wonder when we look at a bird and to ponder about the mystery of its inner life, considering what it knows, and what we do not.

Forrest Martin is an M.A. student and teaching assistant in the Department of Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures. He received his B.A. summa cum laude in Hebrew Bible & ancient Near Eastern studies with a second major in Greek from the University of Washington. He is fascinated by the artistry of ancient texts. His academic interests include a variety of ancient Near Eastern, Mediterranean, and North African languages and literatures, particularly as they relate to ancient religion and conceptions of cosmology. He is the 2022-2023 Ina & Richard Willner Memorial Fellow in Jewish Studies.

Forrest Martin is an M.A. student and teaching assistant in the Department of Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures. He received his B.A. summa cum laude in Hebrew Bible & ancient Near Eastern studies with a second major in Greek from the University of Washington. He is fascinated by the artistry of ancient texts. His academic interests include a variety of ancient Near Eastern, Mediterranean, and North African languages and literatures, particularly as they relate to ancient religion and conceptions of cosmology. He is the 2022-2023 Ina & Richard Willner Memorial Fellow in Jewish Studies.

I am a vegan Christian, and I will definitely be sharing this article! Thank you!