Hebrew verb tense flash card. From The Dusty Scholar.

By Samuel Cantor

When discussing the rewards of learning a foreign language, people are apt to talk about language as a gateway to a new culture. We often hear about learning new words which have no English substitutes, or of particular phrases or idioms which reveal values and habits unknown to us. The general thrust is that when we learn unique words and idioms, we learn something interesting about the lives and perspectives of native speakers.

This is undoubtedly true. However, having spent my entire summer studying modern Hebrew through the generosity of the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies and its opportunity grant program, the experience was eye-opening to me in a completely different sense.

What I found exhilarating about the Hebrew language was, of all things, its grammar. Funny enough, learning a new grammar broadened my perspectives on humanity just as much as learning the slang of a nation on the other side of the world.

Why is grammar special?

Now, I admit that grammar gets a bad rap. The word conjures vivid images of our teachers scolding us for “splitting infinitives” (never mind that I didn’t learn what an infinitive was until I was 21). Learning the grammar of a new language can be one of the most frustrating pieces of the whole experience. While learning new words can be as simple as remembering the look and sound of a set of symbols, learning the grammar of a language involves thinking in a brand new way.

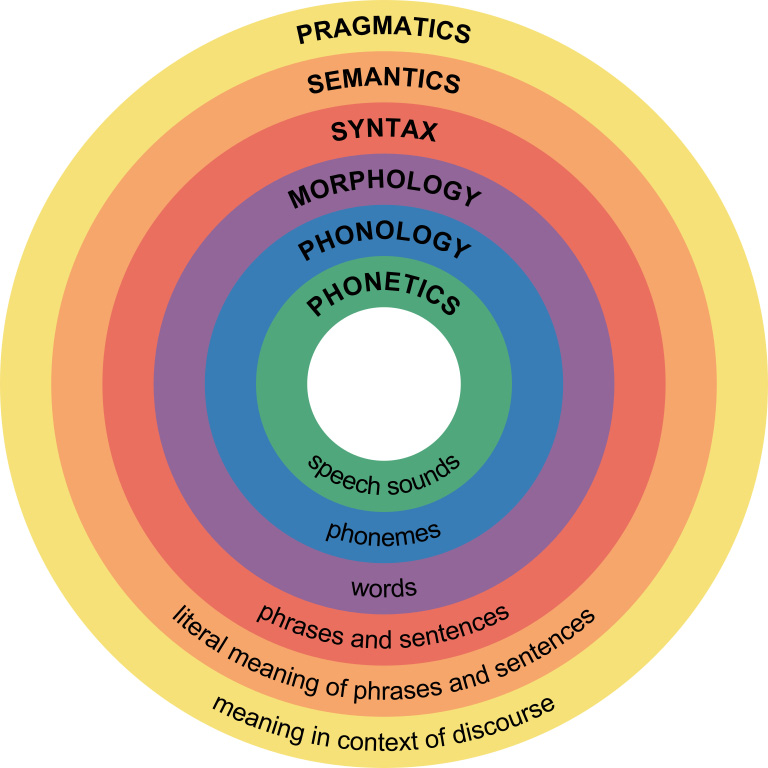

Levels of linguistic structure. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Let me be more specific about what I have in mind when I talk about grammar. Linguists take great pleasure in categorizing the properties of a language. The “pragmatics” of a language are the connotations of words, like how “lady” is more casual than “woman,” and the implications of certain sentences, like how saying “most of the students passed” suggests that some students failed. The “semantics” of a language is essentially its vocabulary – what the words mean, like how in English “red” means red. The “syntax” of a language is its sentence structure.

Ironically, the syntax of a foreign language can be one of the most difficult dimensions to understand precisely because we think so little about the syntax of our own language.

Think of the times you have struggled to put something into words. Usually we know just what we are thinking, but spend our time finding a way to say it that is appropriate for the context (think of how you edit your speech habits around a boss or professor, or around a cool person you just met and want to impress).

However, we rarely have to worry about the grammaticality of what we say. The grammar of our native language is so fundamental to our speech that it’s hard to describe the rules or imagine doing it differently. If you stop and think about it, it’s pretty incredible that we know how to use functional words like “that” and “to,” when to add an “-ing” to the end of a verb, and that “everybody” is a singular noun.

Learning a new language can both show a whole new way of speaking, and teach us things about our native language that we’re often too close to see.

How grammar solves problems

I am not sure if there is a more fundamental word in the English language than the word “is” and its various forms, like “am” and “was.” We can say a great deal with it: “I am Samuel,” “He is happy,” “They were running,” and so on.

It should come as a shock, then, to hear that Hebrew does not have the verb “is” — there is no conjugation of the verb “to be” in the present tense. So how does Hebrew handle basic statements?

For a sentence like “I am happy,” one just has to say the word for “I” and the word for “happy,” with no verb in between (note that Hebrew reads from right to left):

אני שמח

happy I

(“I’m happy”)

The problem is that this strategy doesn’t work for some sentences. Consider the difference between saying “The good teacher is happy and hungry” and “The teacher is good, happy, and hungry.” Without “is,” how do you distinguish between an adjective that directly attaches to the noun (like “good” in “the good teacher”), and an adjective that indirectly attaches to the noun, as if there were a verb linking the two (like “good” in “The teacher is good”)?

In Hebrew, a solution is to use the word for “the”, “ה”, as a marker for adjectives that directly attach to the adjective. Returning to our two examples:

המורה הטוב שמח ורעב

and-hungry happy the-good the-teacher

(“The good teacher is happy and hungry”)

המורה טוב, שמח ורעב

and-hungry happy good the-teacher

(“The teacher is good, happy, and hungry”)

See how that one “ה” makes all the difference?

Sentences with forms like these are essential to language because they express very simple ideas, so of course there is a clear and distinct method for forming them with Hebrew grammar. When there are features that prevent those sentences from being formed in the way that, at least to us, seems the simplest, the language finds a way to get the job done on its own terms.

Hebrew calligraphy by calligrapher michel D’anastasio.

What blows me away is that, like a good mystery or logic puzzle, the “solution” to problems like these seems both really foreign but really straightforward and reasonable at the same time.

Of course, this whole way of talking about language as problems and solutions, questions and answers, is an artifact of my perspective — I am talking about the language like a person who started learning it in their adult life.

We would never talk about our first languages this way. I never think of English as giving me a riddle, or as solving a puzzle. I just speak English because it’s what I know, and I usually feel like it’s me who is in charge, not that I am jumping through hoops.

I said at the start that learning Hebrew broadened my perspective on humanity, and that’s because what’s really amazing, at the end of the day, is all of us. We each have the ability to do incredibly complicated stuff constantly, without even realizing that we’re doing it. It took starting over, learning a grammar from the beginning, and realizing how much work it is to fit words together, to appreciate it.

So I’d like you to ask yourself: What’s in your native language that someone on the other side of the world would find fascinating, or baffling, or brilliant? If you want to find out, I recommend learning another language, and if you want a language with a really different grammar, I recommend Hebrew.

Sam Cantor studies philosophy and linguistics, with a focus on semantics, syntax, the philosophy of language, and logic. He is interested in humans’ natural capacity for language and general lack of knowledge about what it is we are doing when we speak our own first languages fluently and effortlessly.

Sam Cantor studies philosophy and linguistics, with a focus on semantics, syntax, the philosophy of language, and logic. He is interested in humans’ natural capacity for language and general lack of knowledge about what it is we are doing when we speak our own first languages fluently and effortlessly.

Sam:

Thank you for the meaningful essay on Hebrew grammar. As one who knew not at single word at age 29 to one who converses almost as easily as in English, I certainly appreciate your thoughts. I have said to many people how Ivrit has given me an entirely new perspective on the thought process…and by extension, on the culture of a people.

“Derech HaGav, ani moochan ledeber b’Ivrit b’kol hisdamnoot”

Jerry aka “Mardevek”