By Rob Keener

I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that many of us have sat through a boring high school history class before… or more than one. Traditional high school history classes generally cover some amount of geography, some primary source evaluation, some historical cause and effect, and lots of names and dates. It’s pretty much a continual march through history that covers most material in the same way.

Traditional history classes are based around lectures and readings

One of the problems with traditional social studies classes like these is that students retain little of the information teachers cover because they aren’t engaged in the classroom. However, this doesn’t have to be the case. History can be powerful and engaging when it allows students and teachers to understand their current realities, especially difficult topics such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which I have been constructing a curriculum around this year.

The instructional approach of project-based learning (PBL) offers teachers a chance to delve into hard-to-teach topics by creating a “bounded mode of inquiry” that allows them to structure the conversations held in class. PBL helps teachers and students to examine concepts such as nationalism, multiple perspectives on history, human rights, and the emergence of nations that are central to understanding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (and others). Learning about these concepts also enables students to better understand how issues like these shape our lives today.

I should clarify that projects in this sense are not poster boards or activities like building a catapult, which I did in a unit on the Middle Ages in high school.(Somehow I didn’t learn much from that project.) Rather, it refers to a series of learning activities that are directly linked to the development of concepts and learning skills in students. In history, learning skills include sourcing (or cross-referencing), determining causation, evaluating claims, using evidence, contextualizing and corroborating information, and at the center of it all, according to social studies expert Walter C. Parker, “making evidence-based arguments about the past and evaluating the quality of the arguments made by others.” The main goal of PBL is to help students use these skills to experience deep conceptual learning, that is, to use concepts from disciplinary knowledge (i.e., ideas from the disciplines of physics, history, English, algebra, etc.) to “transcend the limits of personal experience.”

My research for this fellowship focuses on how to construct a project-based curriculum where the main concepts from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, such as nationalism and human rights, are a part of recurring sequence that promotes deeper and more authentic learning.

Discussions are an essential part of project-based history classrooms

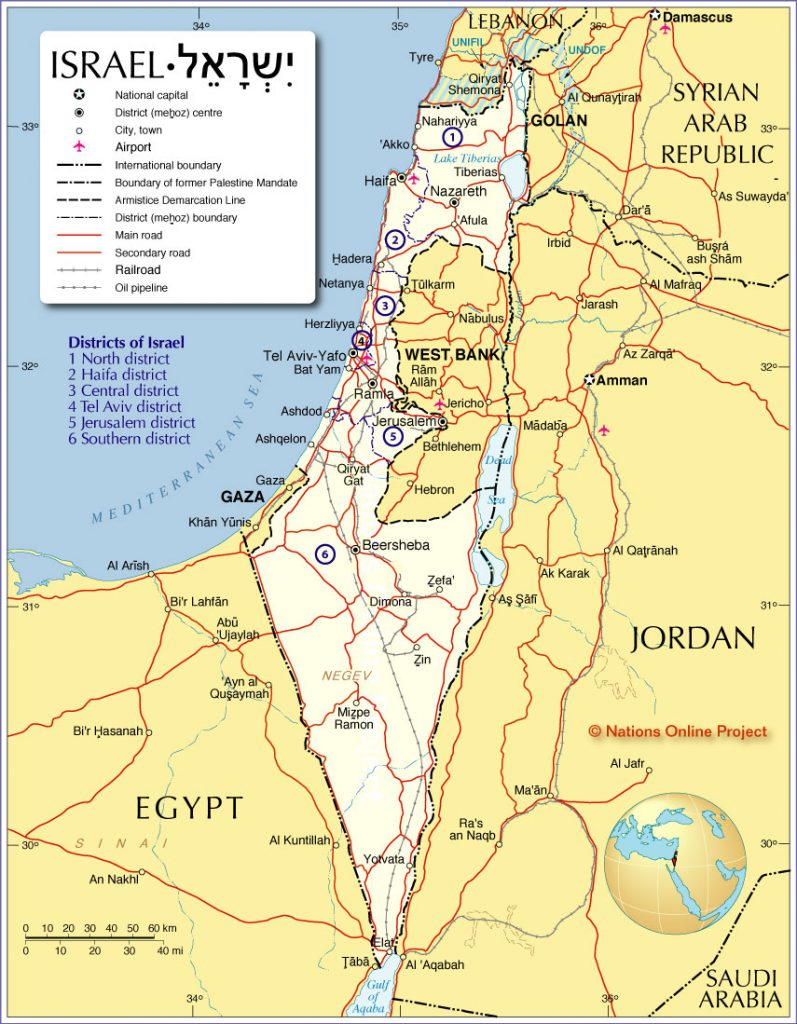

Authentic learning is learning that helps students to understand more about their daily lives and their world. For example, if students can demonstrate deep conceptual knowledge of the human right to freedom of movement, how would this shape their understanding and knowledge of the current security measures and borders in Israel/Palestine? Or how would this contrast with the rejection of Israeli passports in many countries across the globe? Finally, how does this right play out in students’ daily lives in the US, in issues such as our weak national mass transit system?

Throughout the year, students in a project-based classroom engage in projects, discussions, deliberations, primary source analysis and homework to help them build their inquiry (or historical and investigative) skills, allowing them to have deep and authentic conceptual learning experiences. These activities serve as a platform for students to understand the complicated issues within the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Teachers build students up to this place of understanding through yearlong curriculum planning, and seek to continuously “loop” concepts throughout the year.

“Looping” means revisiting certain concepts throughout a semester or year in different contexts. When it has promoted deep and authentic learning, a looped concept such as nationalism will enable students to make links to their world and the rise of nationalism in the 21st century across the globe. Teachers help students to make these connections between the past and the present through projects, discussions, and deliberations.

Political map of Israel

A conceptual loop on nationalism would give students the knowledge necessary to discuss multiple perspectives within Zionism/Jewish nationalism. Students would first analyze certain primary sources, such as Herzl’s “The Jewish State” document, which they would then discuss in groups, interpreting the meaning. This would be followed by a similar process with Vladimir Jabotinksy’s “Iron Wall” document. Students would conclude the lesson by comparing these two different notions of Zionism. The concept of nationalism could then be revisited during a later lesson on the independence of Israel and how different notions of Zionism shaped that process. Lastly, students would discuss how concepts of nationalism inform their own understanding of the current rise of nationalism in society today.

For project-based learning to be deep and rigorous, five things are needed:

1) Projects should be central to the course, not a “reward”

2) Concepts should be the primary focus of the curriculum, not places, dates or events

3) Concepts must be looped and built on top of each other in a way that promotes deeper learning

4) Learning from readings (as homework) should be mandatory. Researchers Walter Parker and Jane Lo found that well-constructed PBL courses encourage students to actually do their reading because they want to perform well in front of their peers in activities. However, readings should be specifically tailored to the upcoming exercise.

5) Engaging activities should come before lectures and PowerPoints. Lectures are more powerful after projects, as a way to review information

Teachers must decide for themselves based on their own curriculum planning which topics related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict will work best, depending on how they and their students are developing looped concepts. The Mandate Period, the emergence of the state of Israel, Israeli expansion into the West Bank, Israeli wars with Hezbollah, and the various attempts at the peace process would all be excellent topics that could help students develop concepts related to the conflict.

Project-based learning is a powerful tool teachers can use to help students engage with difficult topics such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. PBL helps students to develop multiple perspectives on a topic through conceptual looping and build historical thinking skills such as making evidence-based claims and arguments.

Project-based learning also opens windows for teachers and students to see the world in a different way. Far more than traditional classes and their focus on test preparation and rote memorization, project-based learning enables everyone involved to learn deeply about concepts that can be applied to their own lives.

Robert Keener was born in Houston, Texas, where he attended St. Thomas High School and Texas Tech University. After college, Robert spent two years working in the oil and gas industry in Houston before academia came calling. He attended Ole Miss in Oxford, Mississippi, where he took two courses on the history of the Middle East that sparked an interest in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The multi-sided presentation of the conflict by his mentor, Dr. Nikolas Trepanier, was far different than the single-sided polemics that he had previously heard. While at Ole Miss, Robert focused on studying systems of oppression such as apartheid, Jim Crow and imperialism. After earning his MA in history, Robert enrolled in the University of Washington’s Multicultural Education doctoral program, where his research centers on teaching controversial topics in social studies, global citizenship education, and the construction of knowledge. When he is not working as a research assistant at the Center for Multicultural Education or trying to earn his doctorate, Robert enjoys hiking in the mountains with his wife Emily and their chocolate lab named Rylee.

Robert Keener was born in Houston, Texas, where he attended St. Thomas High School and Texas Tech University. After college, Robert spent two years working in the oil and gas industry in Houston before academia came calling. He attended Ole Miss in Oxford, Mississippi, where he took two courses on the history of the Middle East that sparked an interest in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The multi-sided presentation of the conflict by his mentor, Dr. Nikolas Trepanier, was far different than the single-sided polemics that he had previously heard. While at Ole Miss, Robert focused on studying systems of oppression such as apartheid, Jim Crow and imperialism. After earning his MA in history, Robert enrolled in the University of Washington’s Multicultural Education doctoral program, where his research centers on teaching controversial topics in social studies, global citizenship education, and the construction of knowledge. When he is not working as a research assistant at the Center for Multicultural Education or trying to earn his doctorate, Robert enjoys hiking in the mountains with his wife Emily and their chocolate lab named Rylee.

Hi Robert,

I’m a homeschool teacher to two high-schoolers, and we’ve been given the chance to live in Jerusalem for the current school year. I’d love to tailor our history/lit studies to the area were in, and your article describes just the kind of methods I’d prefer to use. My big question is: do you have any list perchance of resources, whether primary documents or recommended documentaries or actual project ideas? I would so appreciate any help you can give me. Thanks! Lisa

Hi Lisa, we haven’t heard back from Rob about this, but some text suggestions he made last year include: excerpts from The Jewish State by Theodore Herzl, writings by Vladimir Jablonsky on a Jewish state, the Israeli Declaration of Independence, and poems by Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti. The Jewish Virtual Library also has a collection of writings on Zionism that could be good candidates. Good luck!