By Makena Mezistrano

Lauren Zarlingo.

A University of Washington undergraduate student is using the tools she’s learned in a Textual and Digital Studies course to bring one aspect of Ladino newspapers into the digital age.

Lauren Zarlingo, a sophomore from Everett, Washington, has encoded (or converted) two English sections of La Vara into a searchable format known as a Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) document. The entire TEI document can be viewed here.

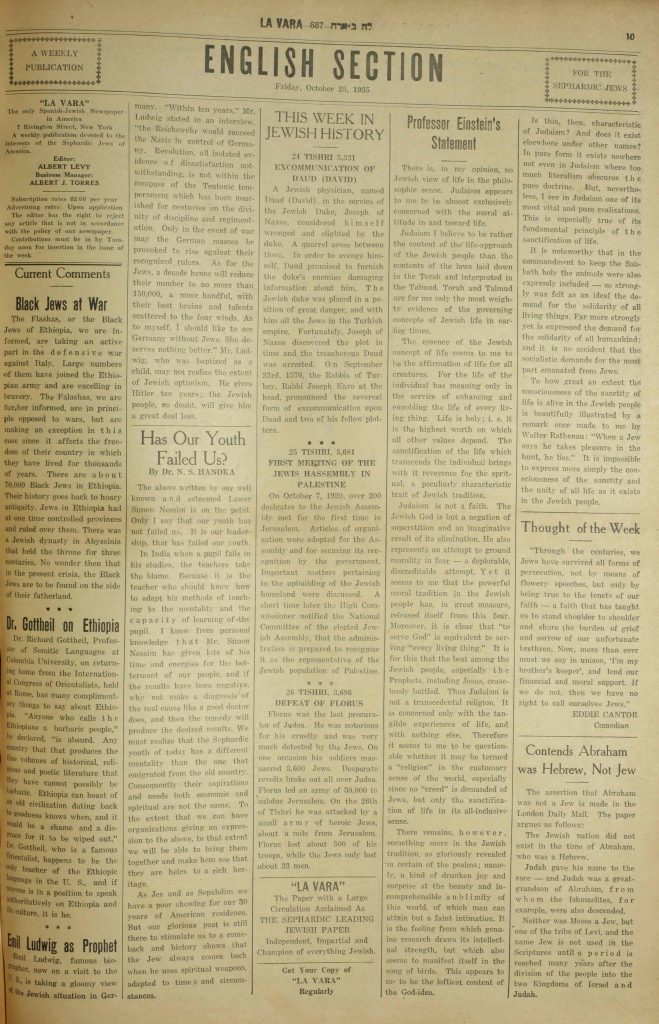

Though primarily a Ladino weekly, La Vara — New York’s longest running Ladino newspaper — also began including an English section in 1934 as its readers became more acquainted with the language. Zarlingo encoded the English sections from two consecutive issues of La Vara published on October 25 and November 1, 1935.

Zarlingo is studying business and minoring in textual studies and digital humanities, and is interested in how humanities intersect with the digital world — especially the ways in which digital tools can be applied to Jewish studies and poetry. These multidisciplinary interests led her to utilize La Vara for her text encoding project.

I sat down with Zarlingo to learn about TEI, her interest in La Vara, and how the skills she’s learning in her textual studies minor can help preserve archival documents.

Your project was for a Textual and Digital Studies (TXTDS) course at the UW called “Texts, Publics and Publication” with Professor Geoffrey Turnovsky. Can you share a bit about this course, why you chose to take it, and some of the most exciting things you learned?

I wanted to develop more technical skills since my major (business) doesn’t put much focus on that area; I loved the idea of attaining those skills through a humanistic lens and connecting different disciplines. I was interested in looking at texts in a new way, and examining the physical form of texts and their publication and circulation, rather than focusing exclusively on close reading like I had done in my previous English classes.

The course definitely lived up to my expectations: Professor Turnovsky was so knowledgeable and great at sharing his knowledge with us. The combination of hands-on work with more theoretical reading really helped solidify the concepts for me.

One of the most important topics we discussed was data preservation and preventing obsolescence. It’s frightening to think about how quickly some methods of data storage came into existence and then passed out of common use. Floppy disks, Fortran punch cards, optical media — how are you even supposed to know what will last and what won’t? And the considerations are very different for books and papers versus digital data. Of course, it was so cool to be able to create my own digital edition of a text. I can’t believe I went from knowing nothing about XML and TEI to having my own full-fledged TEI document in the span of eleven weeks.

(Editor’s note: UW Perspectives highlighted this course and the work of several students in UW Special Collections. Read more in “A Digital Life for Print Texts” by Nancy Joseph.)

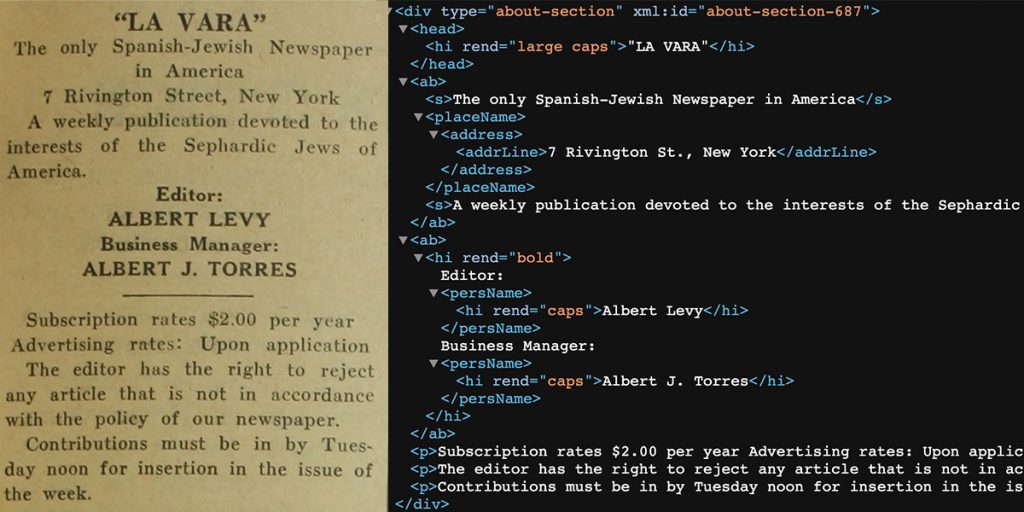

Above, Zarlingo’s encoding of the English masthead of La Vara, printed in the English section of the October 25, 1935 issue. The original text is pictured at right. (Original text taken from ST01101, courtesy Richard Adatto)

Let’s talk a little about those terms you just mentioned: The final output for your project is known as a TEI document, or Text Encoding Initiative document. What is TEI, how is it used, and how can it be harnessed for textual preservation?

TEI is a set of tags and rules for using XML to encode texts. A TEI XML file will include the text itself, as well as information about the text, and metadata. XML is extensible, which means it allows you to make your own tags, so the Text Encoding Initiative has created a standardized set of tags for text encoding.

It’s mostly used in an academic context to preserve texts, both in terms of content as well as other elements like formatting and publishing history. TEI is thought to be one of the best formats for preserving texts over time, ensuring (as much as possible) that they’ll be readable decades down the line.

It can also improve access to archival texts by making them publicly available, searchable, and adaptable to whatever other uses people wish to apply to the text. Other users can take a TEI document and add more text; insert additional and different tags; use a style sheet to make it display in a more readable way; and more.

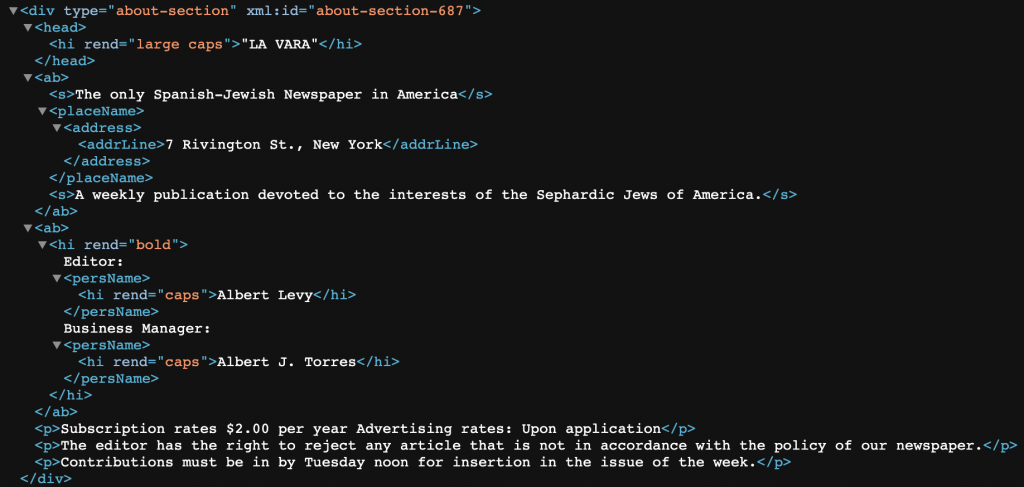

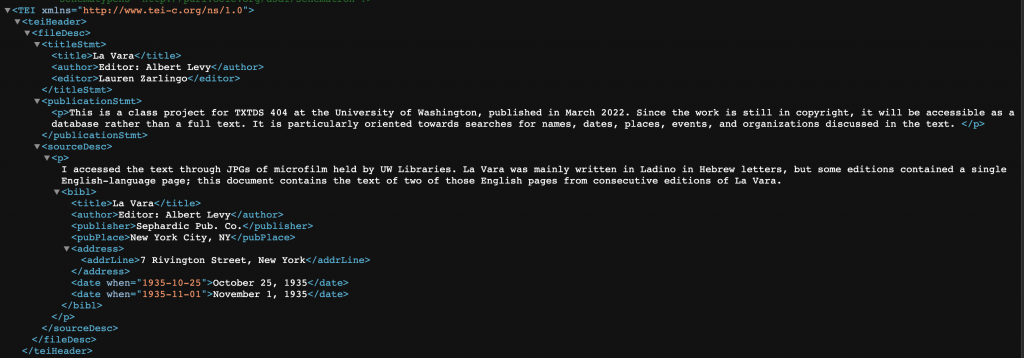

You created a TEI document based on two English sections from the Ladino newspaper La Vara, published in New York from 1922-1948. What were the components of your TEI document?

Besides the text of La Vara itself, TEI also requires the inclusion of metadata in the form of the “teiHeader.” My TEI header contains the tag — which is required in all TEI documents — and a description of my file with the title; information about where, when, and why I published it; and the history of my source material. I’ll add more tags and information to my header in the future, like when I complete the next version of the document to inform users about the revision history.

Zarlingo’s TEI header.

Usually there would be a schema as well, which helps inform other users about how you did things and what parts of TEI you used in your document, but we didn’t make a formal schema for this project. Since time was short we just included a section in our report detailing the tags we used, the structure of our tagging, and the features we focused on encoding. I do hope to add a formal schema in the future.

I wrote a short introduction to contextualize the work for any possible readers who might not be specifically familiar with La Vara. I also wrote a handful of editorial annotations. For me, one of the most important parts of the project was that La Vara should be readable by the widest audience possible. I know the first time I read it, I had a lot of questions about the personalities mentioned in the articles, and the context for the current events covered. I wanted to take all of the information that I, as a reader, had to search for and include it in-line so that readers of my document could have an uninterrupted experience.

Zarlingo’s contextualizing notes.

How did this project fit into the TXTDS course you took?

The project extended our learning in so many ways. We started working on the project as soon as the class started, and we completed the different elements at the same time as we were learning and reading about each of them in class: writing our own informal schema as we were learning about schemas, tagging as we were learning about different tags. Doing that hands-on work really solidified my understanding.

We learned a lot from each other’s projects, as well. A couple of people chose image-heavy texts for their projects, so when they shared their work I got to learn about image description in TEI. Another classmate used the tag as a way of preserving both original and modernized spellings in his document, which was so cool to see in action.

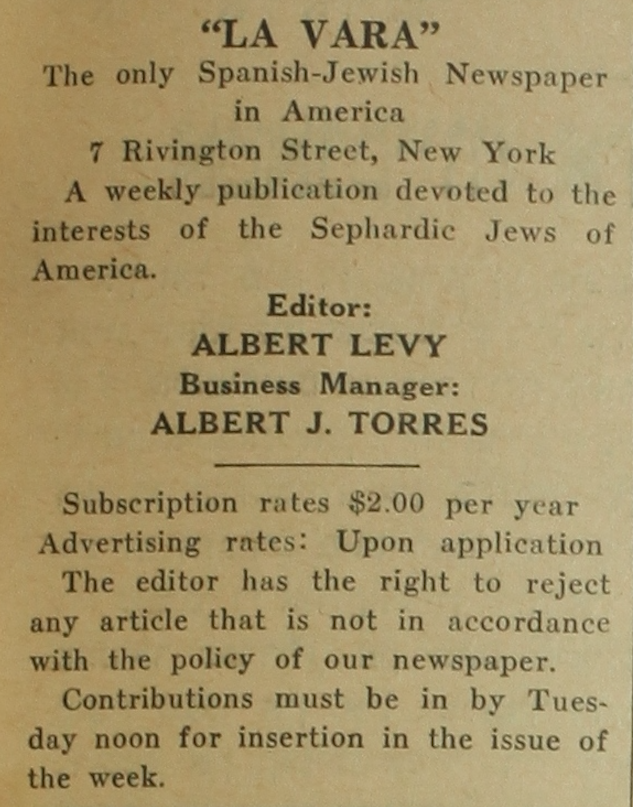

The English section from the October 25, 1935 issue of La Vara. Notice the varied font sizes and styles that were noteworthy to Zarlingo. (ST01101, courtesy Richard Adatto)

What made you choose La Vara for this assignment? Did you know anything about La Vara before you dove in to create a TEI document?

From the start, I was interested in working with a Jewish text of some kind. Professor Turnovsky, the Special Collections librarians, and Sephardic Studies Program staff all worked with me to find a text, and we landed on La Vara. I had previously read a little about La Vara in Professor Devin Naar’s “Sephardic Diaspora” class. La Vara ended up being a great fit for the project and just a fascinating text in general; I’ve since gone down to the microfilm collections in the Suzzallo Library to read more of it.

(Editor’s note: Nearly all issues of La Vara are publicly available online via the National Library of Israel’s Historical Jewish Press website. The project is a result of a collaboration between multiple institutions and libraries, including our Sephardic Studies Digital Collection.)

Some editions of La Vara have a single page written in English rather than Ladino, and I encoded two of those pages. Since the goal I had in mind was to improve access to the public, and the users I had in mind included non-experts who might not know much about Sephardic Jews, I thought focusing on the English-language parts best suited this particular project.

Tell us a little about the process of creating this document: how did you go about transcribing the text of La Vara? Were there any challenges you encountered, such as unusual spellings? Did you ever feel the need to amend the text in any way?

I transcribed the pages by hand. The only unusual spellings I encountered were romanized Hebrew words; I didn’t feel those affected readability, so I didn’t alter them. It’s interesting to see how different spellings of transliterated Hebrew words are popular in different places and times.

I did have to make a lot of decisions about how much of the page formatting to preserve and how to encode things like page layout and different fonts: on the one hand, I had limited time and the physical appearance of the text wasn’t central to my purpose, so I didn’t want to focus too much on it. However, it was also important to me that users get a sense of the visual richness and variety of the text, because those elements made a strong impression on me. I could see that real care was put into rendering the page of the newspaper look interesting. I wanted readers to see that too, so I chose to tag font size and style in the article headings.

What were your goals for the user in creating this document? What do you hope users will be able to find more easily, for instance, by having the English sections of La Vara rendered in a TEI document?

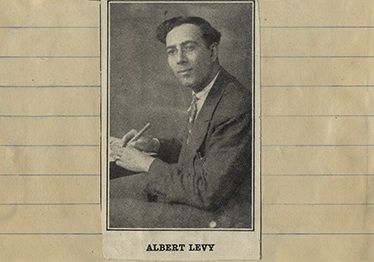

Albert D. Levy in a photo from one of his scrapbooks. (ST00105, courtesy Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation)

These sections of La Vara are now in a format that’s compatible with Internet storage, so it’s widely accessible in a way that it maybe hasn’t been for over eighty years. Readers can now use Internet tools to access a window into the sorts of issues and topics were important to New York Sephardim in the 1930s, and what La Vara editor Albert D. Levy thought was important to cover.

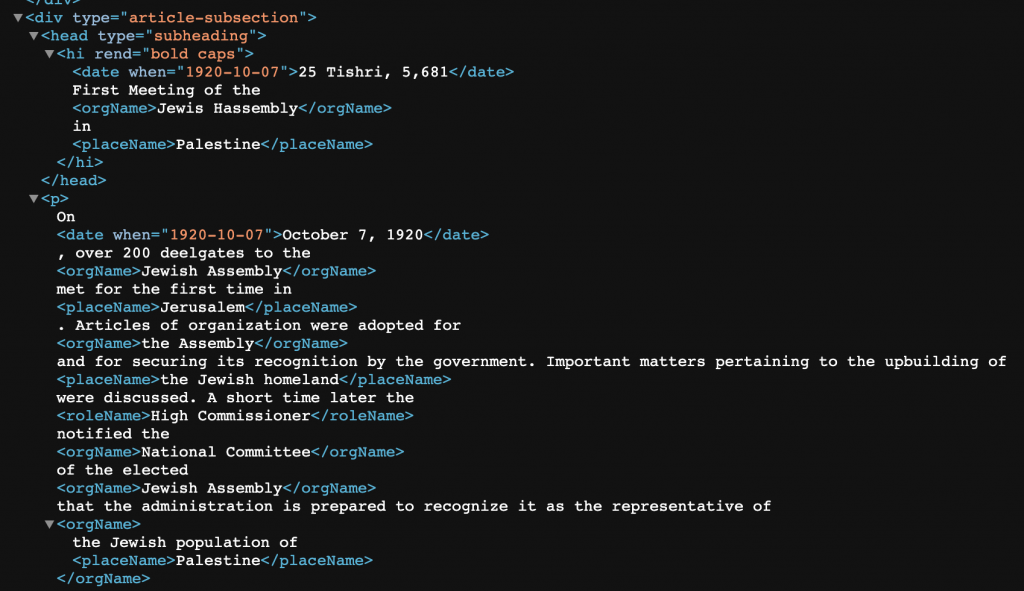

For instance, I wanted to set my document up for searchability so that readers can see which people, places, and events are discussed without reading the entire text. Readers can use XPath (a simple way of writing expressions to query and navigate a document) in an XML editor, or even search the file in-browser by using the “inspect element” feature.

A portion of Zarlingo’s TEI document with various tags, including “placeName”, “orgName”, and “roleName” to denote various aspects of the text.

Another thing I like about having these parts of La Vara in TEI format is the possibilities it opens up for users to pursue their own interests and questions about the text. If somebody else wanted to take this TEI document and add more tags, or transform it into another format, or make a style sheet to display it a certain way, they could do so. If I had just put out, say, an image of the newspaper page, people would be able to read it — which is great — but they wouldn’t be able to do those other things. My long-term goal has always been to add more pages over time — I have three more that I’m working on tagging currently.

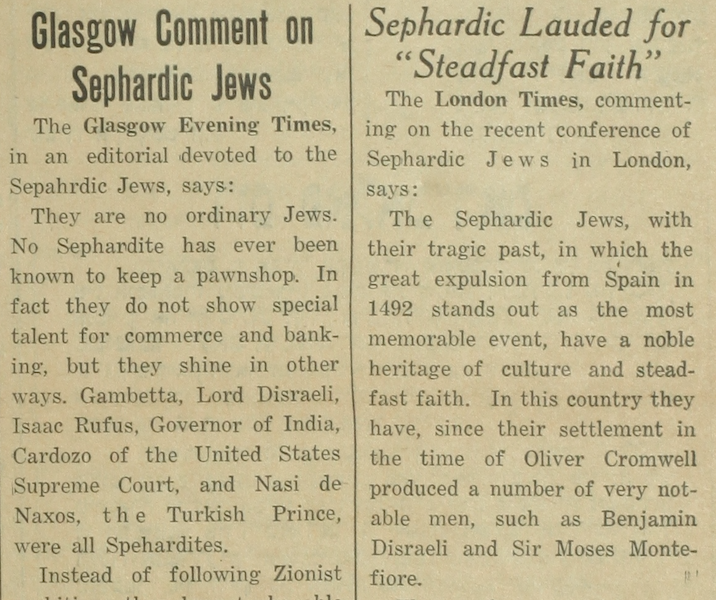

Reportage in the English section of La Vara (November 1, 1935) that references “The Glasgow Evening Times” and “The London Times.” (ST01101, courtesy Richard Adatto)

What did you find most interesting about the sections of La Vara that you read? Was there anything particularly surprising that you found?

I observed a significant focus in the paper on how Sephardim were being portrayed in the wider international press — in “The Glasgow Evening Times,” “The London Times,” and “The London Daily Mail.” I’d like to learn more about why this was a focus.

Do you plan to continue studying Sephardic topics in the future? Do you have an interest in learning Ladino?

I would love to learn Ladino if it’s offered at the UW, or if I can find the opportunity! I sometimes attempt to puzzle through a few words of it with my limited knowledge of Spanish, but knowing Ladino would really open up my access to primary sources, which would be so exciting. The history of Ladino is fascinating to me, especially how it’s picked up elements from other languages across the Sephardic diaspora. (Editor’s note: Ladino will be a central aspect of a new course offered at the University of Washington in fall 2022 called Modern Sephardic Cultures, which will be taught by new Assistant Professor Canan Bolel.

In the near future, I’d like to learn more about romansas and Sephardic music. The limited exposure I’ve had in my classes has made me curious to hear more, and I hope to have time to dive into that this summer.

Further reading

- “Using machine learning to explore photos, illustrations, ads and more in historic Ladino newspapers,” by Ben Lee

- “Ladino newspapers are the new wave in ‘uncharted waters’ of digital history,” by Hannah S. Pressman

- Video: “Teaching Newspapers to Read Ladino, a Heritage Language of Sephardic Jews“

- “Preserving Sephardic History through Interdisciplinary Collaboration: An Interview with Makena Mezistrano and Ben Lee,” by Taylor Soja in “EuropeNow”